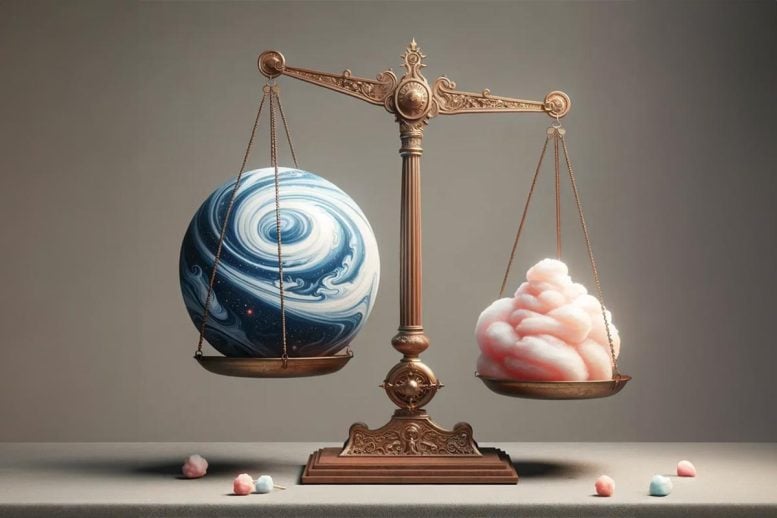

WASP-193b, a new exoplanet, is 50% larger than Jupiter but seven times less massive, with an extremely low density similar to that of cotton candy. Discovered by WASP and confirmed by observatories in Chile, its formation challenges current planetary theories and requires further study. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

This

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>exoplanet is larger but seven times less massive than

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>Jupiter and is the second least dense planet discovered to date.

An international team led by researchers from the EXOTIC Laboratory at the University of Liège, in collaboration with

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>MIT and the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, has just discovered WASP-193b, a giant planet of extraordinarily low density orbiting a distant Sun-like star.

A recently discovered planet, located about 1,200 light years from Earth, is 50% larger than Jupiter but seven times less massive. This gives it an extremely low density, comparable to that of cotton candy.

“WASP-193b is the second least dense planet discovered to date, after Kepler-51d, which is much smaller,” explains Khalid Barkaoui, postcostral researcher at the EXOTIC Laboratory at ULiège and first author of the article published in Natural astronomy. Its extremely low density makes it a real anomaly among the more than five thousand exoplanets discovered to date. This extremely low density cannot be reproduced by standard models of irradiated gas giants, even under the unrealistic assumption of a coreless structure.

Discovery and initial observations

The new planet was initially spotted by the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP), an international collaboration of academic institutions that together operated two robotic observatories, one in the Northern Hemisphere and one in the Southern Hemisphere. Each observatory used an array of wide-angle cameras to measure the brightness of thousands of individual stars across the sky.

In data taken between 2006 and 2008, and again between 2011 and 2012, the WASP-South observatory detected periodic transits, or dips in light, of the star WASP-193. Astronomers determined that the star’s periodic dips in brightness corresponded to a planet passing in front of the star every 6.25 days. The scientists measured the amount of light blocked by the planet during each transit, which gave them an estimate of the planet’s size.

Artist’s impression of the density of WASP-193b compared to cotton candy. Credit: University of Liège

Detailed measurements and surprising density

The team then used the TRAPPIST-Sud and SPECULOOS-Sud observatories — led by Michaël Gillon, FNRS research director and astrophysicist at ULiège — located in the Atacama Desert in Chile to measure the planetary signal in different lengths. wave and validate the planetary character of the wave. eclipsing object. Finally, they also used spectroscopic observations collected by the

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>HARPS and CORALIE spectrographs – also located in Chile (

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>ESO) – to measure the mass of the planet.

To their surprise, the accumulated measurements revealed an extremely low density for the planet. Its mass and size, they calculated, were about 0.14 and 1.5 of Jupiter’s, respectively. The resulting density was approximately 0.059 grams per cubic centimeter.

Jupiter’s density, on the other hand, is about 1.33 grams per cubic centimeter; and Earth is 5.51 grams per cubic centimeter. One of the materials closest in density to the new puffy planet is cotton candy, which has a density of about 0.05 grams per cubic centimeter.

The mystery of WASP-193b’s composition

“The planet is so light that it is difficult to imagine an analogous material in the solid state,” explains Julien de Wit, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and co-author. “The reason it’s close to cotton candy is because both are quite airy. The planet is basically super fluffy.

Researchers suspect the new planet is made mostly of hydrogen and helium, like most other gas giants in the galaxy. For WASP-193b, these gases likely form an extremely inflated atmosphere that extends tens of thousands of kilometers farther than Jupiter’s own atmosphere. How exactly a planet can swell so much is a question that no existing theory of planetary formation can yet answer. This certainly requires a significant deposit of energy inside the planet, but the details of the mechanism are not yet understood.

Future research and challenges

“We don’t know where to place this planet in all the formation theories we currently have, because it’s an outlier among all of them. We cannot explain how this planet formed. Examining its atmosphere more closely will allow us to constrain a path of evolution of this planet, adds Francisco Pozuelos, astronomer at the Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia (IAA-CSIC, Granada, Spain).

“WASP-193b is a cosmic mystery. Its resolution will require more observational and theoretical work, in particular to measure its atmospheric properties with the JWST space telescope and compare them to different theoretical mechanisms that could lead to such extreme inflation,” concludes Khalid Barkaoui.

For more on this discovery, see Discovery of super fluffy ‘cotton candy’ exoplanet shocks scientists.

Reference: “An extended low-density atmosphere around the Jupiter-sized planet WASP-193 b” by Khalid Barkaoui, Francisco J. Pozuelos, Coel Hellier, Barry Smalley, Louise D. Nielsen, Prajwal Niraula, Michael Gillon, Julien de Wit, Simon Muller, Caroline Dorn, Ravit Helled, Emmanuel Jehin, Brice-Olivier Demory, Valérie Van Grootel, Abderahmane Soubkiou, Mourad Ghachoui, David. R. Anderson, Zouhair Benkhaldoun, François Bouchy, Artem Burdanov, Laetitia Delrez, Elsa Ducrot, Lionel Garcia, Abdelhadi Jabiri, Monica Lendl, Pierre FL Maxted, Catriona A. Murray, Peter Pihlmann Pedersen, Didier Queloz, Daniel Sebastian, Oliver Turner, Stéphane Udry, Mathilde Timmermans, Amaury HMJ Triaud and Richard G. West, May 14 Natural astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02259-y