With the announcement of a 300 billion yuan ($41 billion) fund to support public purchases of unsold housing, the Chinese government last week appeared to finally deploy major firepower to confront a three-year slowdown in the country’s real estate market.

But even though the new measures could mark a turning point in a crisis that has weighed heavily on China’s economy, analysts and economists say the hundreds of billions of renminbis are far from enough.

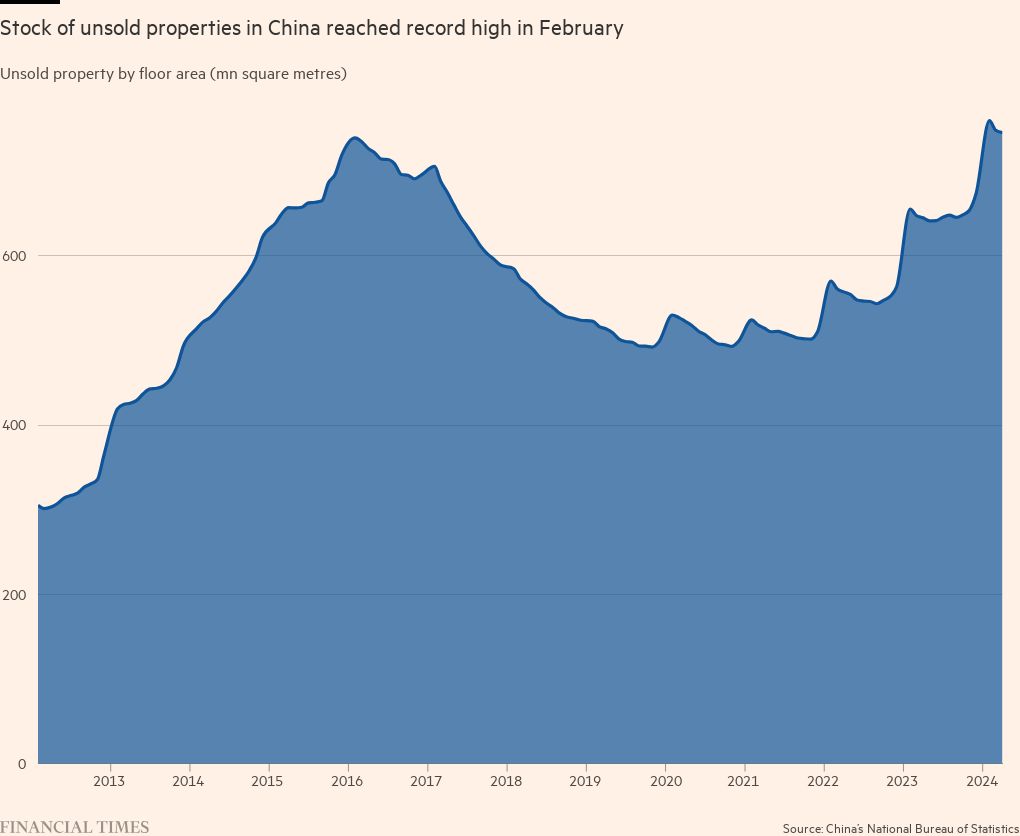

“It’s a drop in the ocean given the scale of unsold inventory,” said Harry Murphy Cruise, an economist at Moody’s Analytics.

Goldman Sachs estimated last week that, on a cost basis, China has RMB 30 trillion of unsold housing, spanning land and completed apartments, equivalent to 10 times the amount sold last year .

Although estimates of China’s unsold housing stock vary, they generally dwarf the financing revealed Friday by the People’s Bank of China. The money is intended to be loaned through banks to help local public companies buy unsold properties, which could then be used as social or affordable housing.

“No matter how you slice it, it seems like the size and scale of the problem is much bigger than what we can see (from) the financing committed by the central government,” said Hui Shan, chief economist for the China at Goldman. Sachs. “The calculations (show) that there is an oversupply problem in the real estate market.”

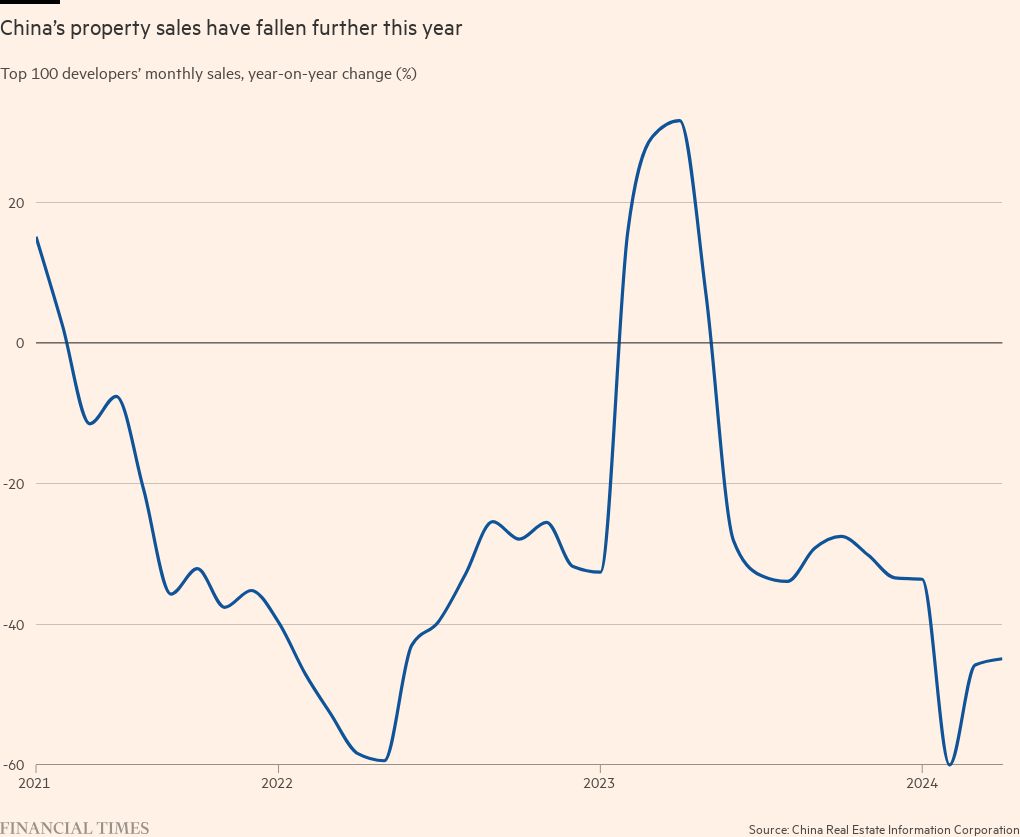

After decades of meteoric expansion, China’s vast real estate sector came to a halt in 2021 after large private developers such as Evergrande ran out of cash. A year earlier, Beijing, wary of an overheating of the real estate market, had imposed restrictions on the sector’s debt.

Since then, safer, state-linked developers have become embroiled in the downturn and confidence has failed to rebound.

Beijing has responded primarily by encouraging the completion of unfinished residential projects, which are typically purchased in advance in China.

His new measures released Friday, which also included removing minimum mortgage rates and reducing down payments for first-time home buyers, reflect the need to more urgently resurrect the market that for decades anchored economic growth and household wealth in China.

But the move highlights the same caution that led policymakers several years ago to rein in expansive private developers, fearing development overheating.

“It’s not like the great financial crisis, where the Federal Reserve bought all the troubled assets of financial institutions,” said Leonard Law, senior credit analyst at Lucror Analytics in Singapore. “What China is trying to do is much more targeted,” because it “still has to combat moral hazard and be careful not to re-inflate the bubble.”

At a news conference in Beijing on Friday, the term “marketization,” a common refrain referring to the need for market-oriented principles in policymaking, was mentioned 15 times.

Such principles, Law said, were evident in all of Beijing’s moves during the property crisis, and ultimately meant that the approach “must be profitable or at least not loss-making for the government entity that provides support.”

Past policy measures, including opening credit lines to developers from state banks, have failed to restore confidence.

Analysts at Morgan Stanley said the new measures “strike a good balance between providing some cushion while letting the real estate cycle run its course without increasing risks for state-owned companies and local banks.”

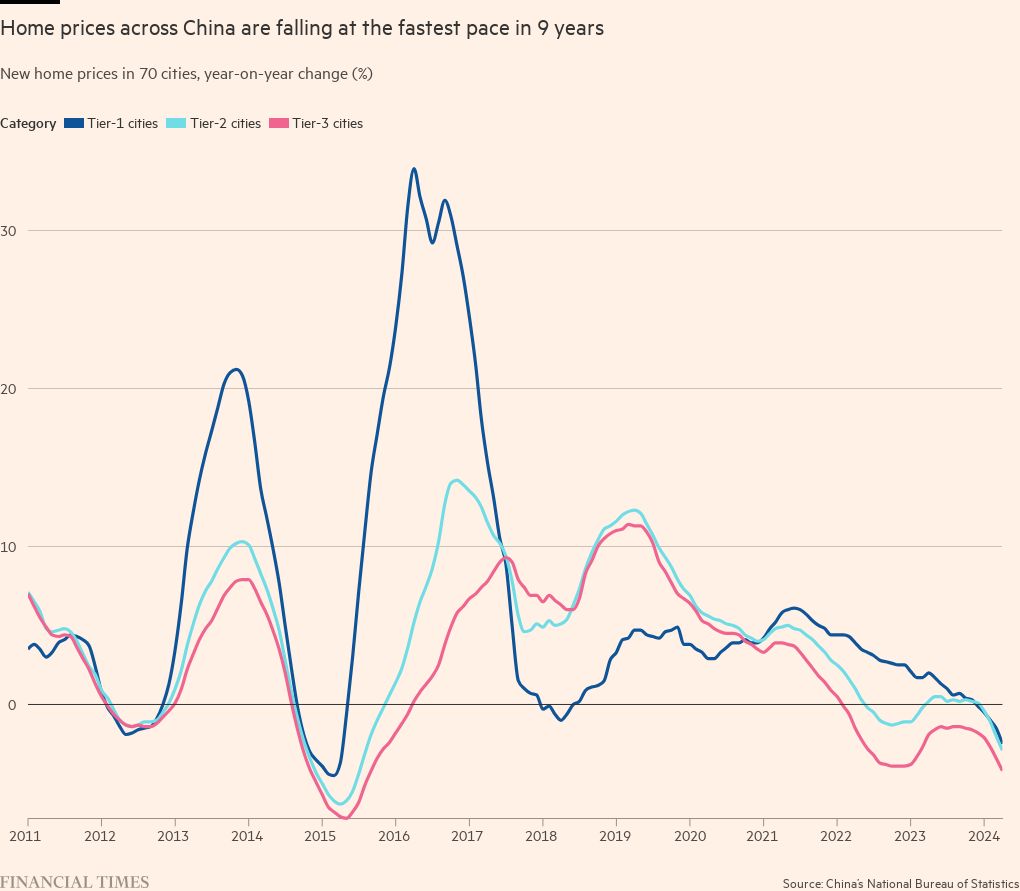

But falling prices have imposed an increasingly pressing financial risk during the housing sector’s three-year downturn. In April, new home prices fell at the fastest monthly rate in nine years.

And Goldman Sachs estimated that in addition to unsold housing stock, there were 90 million to 100 million “phantom supply” units in China that were often purchased as investment properties and had not been lived in.

“China’s financial system is largely bank-driven, and bank loans are largely collateralized by real estate in one form or another,” said Goldman Sachs’ Shan. “That could be a reason why they think it’s important to set a floor price.

“I think maybe this is the start of a new approach,” she added. “If they realize that prices are continuing to fall and sales are not picking up, I imagine central government will have to increase the funding they provide. »

UBS estimated that, based on inventories in 35 major cities, it would cost the government up to RMB 2.4 billion to bring excess inventories of completed but unsold housing back to normal levels.

Tao Wang, UBS’s chief China economist, said that although the PBoC figure was lower than that, the policy direction was encouraging. “We think this is probably a starting point and we think it will probably take more, but it’s not clear to what extent,” she said Monday during a briefing. press.

She added that the measures would not affect her forecast of GDP growth of 4.9 percent this year. “We don’t really expect a major recovery or growth” in the housing market this year, she said. “We’re just looking for stabilization.”

Well before Friday’s announcement, the government had said it would increase the number of social housing units as part of a wider push for redistributive policies. Under its 14th five-year plan, unveiled in 2020, Beijing pledged to provide 6.5 million government-subsidized rental homes in 40 cities.

Karl Choi, head of Greater China real estate research at BofA Global Research, said the new measures could “kill two birds with one stone”.

“We, in the markets, were saying: there is already too much excess supply, why build more social housing?” he said.

He added that the push for affordable housing was linked to higher-tier cities with an influx of population.

The loan facility is “not huge, but it’s not insignificant,” Choi said, highlighting its potential use in Tier 2 cities.

In lower-tier cities, where many developers have expanded aggressively in pursuit of higher margins, the relevance of social housing is less clear.

“We must recognize that the government will not be able to buy back all the stocks,” Shan said. “They’re going to have to make an effort to buy selectively in certain cities and design the program to achieve their policy goals. What they are doing now is extremely insufficient. »

Additional reporting by Wenjie Ding in Beijing