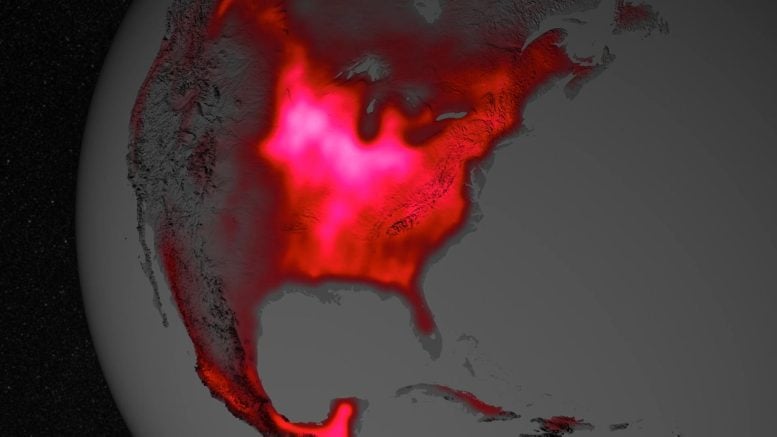

NASA scientists have discovered that satellite-tracked plant fluorescence can predict sudden droughts months in advance, helping to mitigate and understand carbon cycle impacts during droughts. Credit: NASA Science Visualization Studio

An unusual increase in plant productivity can signal an impending serious loss of water in the soil.

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>NASA satellites track this subtle glow, providing early warnings of potential sudden droughts in various landscapes.

Expanding rapidly and without warning, the drought that hit much of the United States in the summer of 2012 was one of the most widespread the country had seen since the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s. lightning strike,” fueled by extreme heat that destroyed soil and plant moisture, led to widespread crop failures and economic losses costing more than $30 billion.

While archetypal droughts can develop over the seasons, flash droughts are characterized by rapid drying. They can set in within a few weeks and are difficult to predict. In a recent study, a team led by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California was able to detect signs of sudden drought up to three months before they appeared. In the future, such advance notice could facilitate mitigation efforts.

How did they do it? By following the glow.

In a western Kentucky field, a machine sprays cover crops to prepare for planting season. NASA scientists are turning to space tools to help them predict the quick, stealthy droughts responsible for severe agricultural losses in recent years. Credit: US Department of Agriculture/Justin Pius

A signal seen from space

During

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>photosynthesis, when a plant absorbs sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into food, its chlorophyll “leaks” some unused photons. This faint glow is called solar-induced fluorescence, or SIF. The stronger the fluorescence, the more carbon dioxide a plant extracts from the atmosphere to fuel its growth.

Although the glow is invisible to the naked eye, it can be detected by instruments aboard satellites such as NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Obsevatory-2 (OCO-2). Launched in 2014, OCO-2 observed the American Midwest lit up during the growing season.

Growing plants emit a form of light detectable by NASA satellites orbiting hundreds of miles above Earth. Parts of North America appear to glow in this visualization, representing an average year. Gray indicates regions with little or no fluorescence; red, pink and white indicate high fluorescence. Credit: NASA Science Visualization Studio

The researchers compared years of fluorescence data to an inventory of flash droughts that hit the United States between May and July 2015 and 2020. They discovered a domino effect: In the weeks and months before a flash drought, the Vegetation first flourished when conditions changed. hot and dry. The flourishing plants were emitting an unusually strong fluorescence signal for the time of year.

But by gradually reducing soil water reserves, plants created a risk. When extreme temperatures hit, already low humidity levels dropped and a sudden drought developed within days.

The team correlated the fluorescence measurements with humidity data from NASA’s SMAP satellite. Short for Soil Moisture Active Passive, SMAP tracks changes in soil water by measuring the intensity of natural microwave emissions from the Earth’s surface.

The scientists found that the unusual pattern of fluorescence correlated extremely well with soil moisture losses during the six to 12 weeks before a sudden drought. A consistent pattern has emerged across diverse landscapes, from the temperate forests of the eastern United States to the great plains and shrublands of the west.

For this reason, plant fluorescence “shows promise as a reliable early warning indicator of sudden drought, with ample time to act,” said Nicholas Parazoo, an Earth scientist at the University of Washington.

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>JPL and lead author of the recent study.

Jordan Gerth, a scientist with the National Weather Service Observations Office who was not involved in the study, said he was glad to see work on flash droughts in light of climate change. He stressed that agriculture benefits from predictability as much as possible.

Although early warning cannot eliminate the impacts of flash droughts, Gerth said, “farmers and ranchers with advanced operations can better use water for irrigation to reduce impacts on crops, avoid planting crops likely to fail or planting a different type of crop. to get the most ideal yield if they have weeks or even months of lead time.

Tracking carbon emissions

In addition to trying to predict flash droughts, scientists wanted to understand their impact on carbon emissions.

By converting carbon dioxide into food during photosynthesis, plants and trees are carbon “sinks,” absorbing more CO2 from the atmosphere than they release. Many types of ecosystems, including agricultural lands, play a role in the carbon cycle, the constant exchange of carbon atoms between the land, atmosphere and ocean.

Scientists used carbon dioxide measurements from the OCO-2 satellite, along with advanced computer models, to track carbon uptake by vegetation before and after flash droughts. Plants under heat stress absorb less CO2 from the atmosphere, so the researchers expected to find more free carbon. What they found instead was a balancing act.

Warm temperatures preceding the onset of the flash drought prompted plants to increase their carbon uptake compared to normal conditions. This anomalous uptake was, on average, sufficient to fully offset decreases in carbon uptake due to subsequent warm conditions. This surprising discovery could help improve predictions from carbon cycle models.

Celebrating its 10th year in orbit this summer, the OCO-2 satellite maps natural and human-caused carbon dioxide concentrations and vegetation fluorescence using three camera-style spectrometers tuned to detect the light signature unique CO2. They measure the gas indirectly by tracking the amount of reflected sunlight it absorbs in a given column of air.