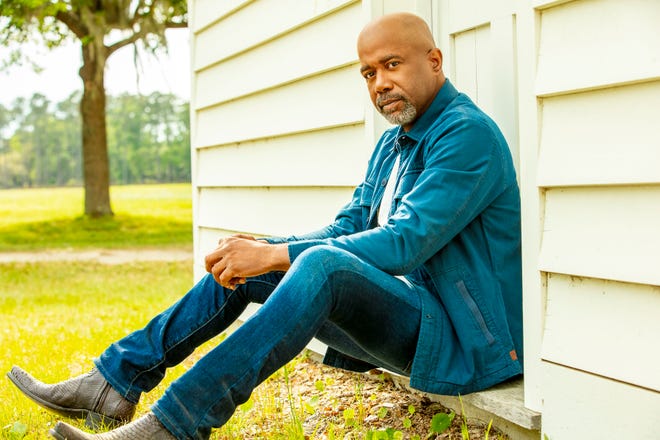

As frontman for Hootie & the Blowfish, Darius Rucker sold 21 million albums of the band’s debut album, “Cracked Rear View,” shared microphones with Frank Sinatra and Adele, and ingested copious amounts of alcohol and of drugs.

It was, for many years in the mid-’90s, the epitome of the stereotypical rock star living as the band blossomed from newcomers in college dorm rooms barely given the chance to fill the radio arena leading with “Hold My Hand” and “Let Her Cry”. »

Rucker, 58, even asked his sports idol Dan Marino of his beloved Miami Dolphins to star in Hootie’s light-hearted video for “Only Wanna Be With You.”

“He’s the best quarterback to ever play the game. Fight me,” Rucker said with a smile during a recent conversation.

His dedication to the Dolphins, KISS, Barry Manilow and music in general is celebrated through his talent for effortless conversation in “Life’s Too Short: A Memoir” (HarperCollins, 242 pp.), available now.

Need a break? Play the USA TODAY daily crossword puzzle.

Darius Rucker is not afraid of painful memories

But his book, which he worked on for a year and a half with author Alan Eisenstock and which recounts not only his highs in Hootie but also his successful move to country music, also delves deeper into family conflicts.

The sudden death of his older brother, Ricky, who died following a drunken accident when Rucker was a child. The pain of a neglectful father that appeared sparingly during his youth, then disappeared for 15 years until resurfacing during the success of Hootie to ask for money to buy a car. The death of his beloved mother, Carolyn, in 1992 (Rucker named his 2023 country album “Carolyn’s Boy” in tribute).

“I laugh and say, ‘My therapist had a lot of work after writing the book,'” Rucker says. “Because we simply don’t deal with trauma. You don’t think about it because you’re grown up and you have kids and bills and bills and kids. When I started writing about it, it all came back and (I realized), wow, I have to deal with this stuff because it really affected me a lot more than I thought.

Darius Rucker strongly believes in destiny

Rucker’s memories—the most painful and the most ecstatic—are recounted in chapters introduced by song titles: Billy Joel’s “Honesty” for his eventual duet with guitarist Mark Bryan and their discussions about forming a band ; “Ships” by Barry Manilow about his fleeting relationship with his father; “So. Central Rain” from one of Hootie & the Blowfish’s biggest inspirations, REM, in the chapter about Rucker meeting bassist Dean Felber, who became both a kindred spirit and a member of the band . (“We share a kind of unity,” Rucker writes. “Dean and I are two halves of a whole. … He is the brother I always wanted.”)

Rucker said that with every memory he recounted — and all of his stories in the book come from memories, not journals — “there was a song that came to me.”

The true formation of Hootie & the Blowfish was built on destiny. Rucker was about to leave the University of South Carolina after a year of feelings of loss and depression when, days before the end of the semester, he made a friend in fellow student Chris Carney.

The two hit it off so quickly that Rucker decided to stay at the school. If he had left as planned, there would have been no meeting with Bryan Felber and, eventually, drummer Jim “Soni” Sonefeld, and therefore no Hootie.

Carney is currently Rucker’s business manager – “He runs my life!” » – and Rucker remains a firm believer in destiny.

“I think the universe brought Hootie & the Blowfish together,” he says. “If you look at all our stories… Soni went to South Carolina because it was the only school to give him a football scholarship. For what? I don’t know, but he has one. Mark wanted to go to James Madison University but couldn’t get in, so he went to South Carolina. Dean was supposed to go to Elon University on a scholarship and decided at the last minute to go to South Carolina. If I leave, Hootie will never arrive. Probably if one of these guys leaves, Hootie will never arrive. So I believe a lot in destiny and the universe.

The non-stop party that was Hootie & the Blowfish: “Whatever you have, I’m in it”

Many of the stories in the book are accompanied by frank acknowledgment of drug use.

“The party never stops,” Rucker writes. “Whatever you have, I’m part of it.”

Mushrooms. Ecstasy. Cocaine.

“When do we participate?” Day, evening, night, until the next day, always. Nonstop,” he writes after an anecdote about handing a bag of $30,000 in cash to a drug dealer.

Rucker now says he’s broken out of a 20-year cycle of heavy drug use — a mandate from his ex-wife, Beth Leonard, who is the mother of two of his children, Daniella, 23, and Jack, 19. (Rucker was arrested in Tennessee in February on two counts of possession of marijuana and Psilocyn stemming from an incident in 2023 when he was stopped for having an expired license plate.)

“When Beth told me to stop, I stopped and said, ‘I’m not doing it anymore.’ And I was lucky to be able to do that,” Rucker says. “I was lucky to not have to go to rehab and all the things that you usually have to do to end it. But it was just time for me to grow up. …If someone offered me something like that (right now), I’d ask, “What’s wrong with you, man?” Those days are long gone.”

Darius Rucker Thrives in Country Music: ‘The Best Revenge is Success’

As Hootie & the Blowfish were “coming to an end” – but not a breakup, as they resumed touring in 2019 and will hit the road again this summer with Collective Soul and Edwin McCain – Rucker decided he would head to Nashville , Tennessee.

Much like the early Hootie years, his attempts to infiltrate the country cliques that dominated the town were initially met with indifference. As a black man trying to make it, even with name recognition, the challenges were magnified.

Rucker essentially returned to his troubadour roots, visiting hundreds of radio stations and simply asking for his single “Don’t Think I Don’t Think About It” to have a chance to make the rotation.

He ended up with a No. 1 hit and a thriving country career that included an invitation to the Grand Ole Opry in 2012 as only — and still — the second black artist inducted.

Rucker says he hopes his success has pushed the industry toward greater acceptance.

“When I arrived, none of us had a chance. And to go out there and prove it wrong was huge,” he says. “I always say that the best revenge is success. So you just have to put your head down and work. That’s what I’ve always done. That’s what Hootie did. You don’t have to speak. You just do it and you live it.