The Banksy Museum in New York features replicas of 160 original Banksys. This one is called “Good Doctor” and was originally stenciled in New York in 2010.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

The Banksy Museum in New York features replicas of 160 original Banksys. This one is called “Good Doctor” and was originally stenciled in New York in 2010.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

New York’s new Banksy Museum attempts to recreate the experience of coming across Banksy graffiti in nature. There’s a fake manhole cover here, some artfully arranged debris there, and wall after wall made to look like brick or concrete and stencilled with Banksy’s iconic images of children, police officers and rats.

But there is a catch: these are not real Banksys, and Banksy has never agreed to have his work reproduced.

Museum founder Hazis Vardar, who privately collects original Banksys and opened a museum of replicas in Paris several years ago, said he was not worried about the artist’s lack of involvement.

“Banksy changed the rules. If you want to do something about Banksy, you also have to change the rules,” he said during a recent tour of the exhibition.

Vardar described Banksy as a pirate and said he identified with that. “Pirate” might be a good description. For decades, the British street artist has exploited his anonymity, surprising city dwellers and the art world with his satirical murals and pop-up exhibitions that suddenly appear overnight.

But because most of Banksy’s graffiti is created on walls and buildings that don’t belong to the artist, it technically constitutes vandalism — and it’s often weather-damaged, repainted by other people, or sold for sale. private galleries and collectors.

This museum reproduction is based on ‘Hula-Hoop Girl’, which appeared in Nottingham, UK in 2020.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

This museum reproduction is based on ‘Hula-Hoop Girl’, which appeared in Nottingham, UK in 2020.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

“Sometimes the city cleaning crew just cleans in the morning,” Vardar explained. In its spirit, the Banksy Museum preserves Banksy’s work for the benefit of the public.

But that’s not how Leila Amineddoleh, art and intellectual property lawyer, sees things.

“There are tons of replicas of the Mona Lisa, and it doesn’t preserve the original,” she said. “I would say the same thing for Banksy.”

Many of Banksy’s works are site-specific, with a particular context in mind. For example, the museum reproduces an image of a young girl floating in the distance while clinging to a handful of balloons, which was originally painted on the West Bank fence and appeared to comment on the plight of the Palestinians . Amineddoleh argued that by placing such art inside and charging a $30 entrance fee, the museum was not only changing its meaning, but also undermining Banksy’s core mission.

“Subversion, making his message available to the public for free, that’s a very important part of Banksy’s message,” she said.

The artist already said no – sort of

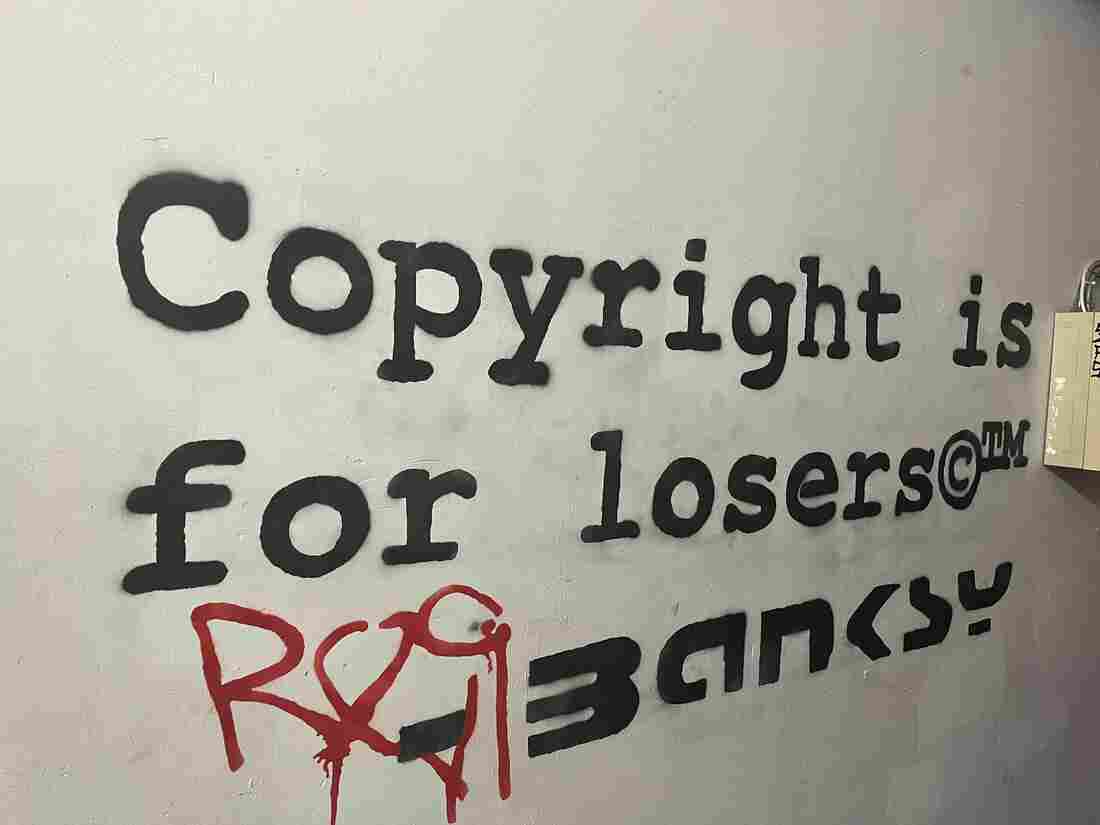

Banksy has already made it clear that he does not want his work used in this way. Pest Control, the company that manages Banksy’s licenses, has denounced anyone profiting from the artist’s work on its website. And in his 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop, the artist criticized the commercialization of street art. On one of the museum’s stairs, there is a Banksy quote painted on the wall that says: “Copyright is for losers.”

The museum put this quote from Banksy’s 2005 book Wall and roomin a stairwell.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

The museum put this quote from Banksy’s 2005 book Wall and roomin a stairwell.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

Neither Pest Control nor Banksy responded to requests for comment on Vardar’s exhibitions. But Amineddoleh said that while Banksy’s views on licensing and intellectual property are part of what makes him such an interesting artist, it doesn’t change how the law applies to him.

“He automatically had a copyright when he created this work,” she said. “The fact that he doesn’t like copyright doesn’t really make a difference.”

What’s a little more complicated, she says, is how another law, the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), might apply to a street artist like Banksy. If any of the museum’s works were created on property owned by the artist, the artist could file a lawsuit with VARA to have their name removed from the Vardar Museum’s unauthorized versions. But that law hasn’t been tested on vandalism, Amineddoleh said, so it’s unclear whether or not it would extend protections to Banksy on pieces he doesn’t technically own.

Vardar’s response: If Banksy has problems with the museum, he could take legal action.

Why doesn’t Banksy take museums like this to court?

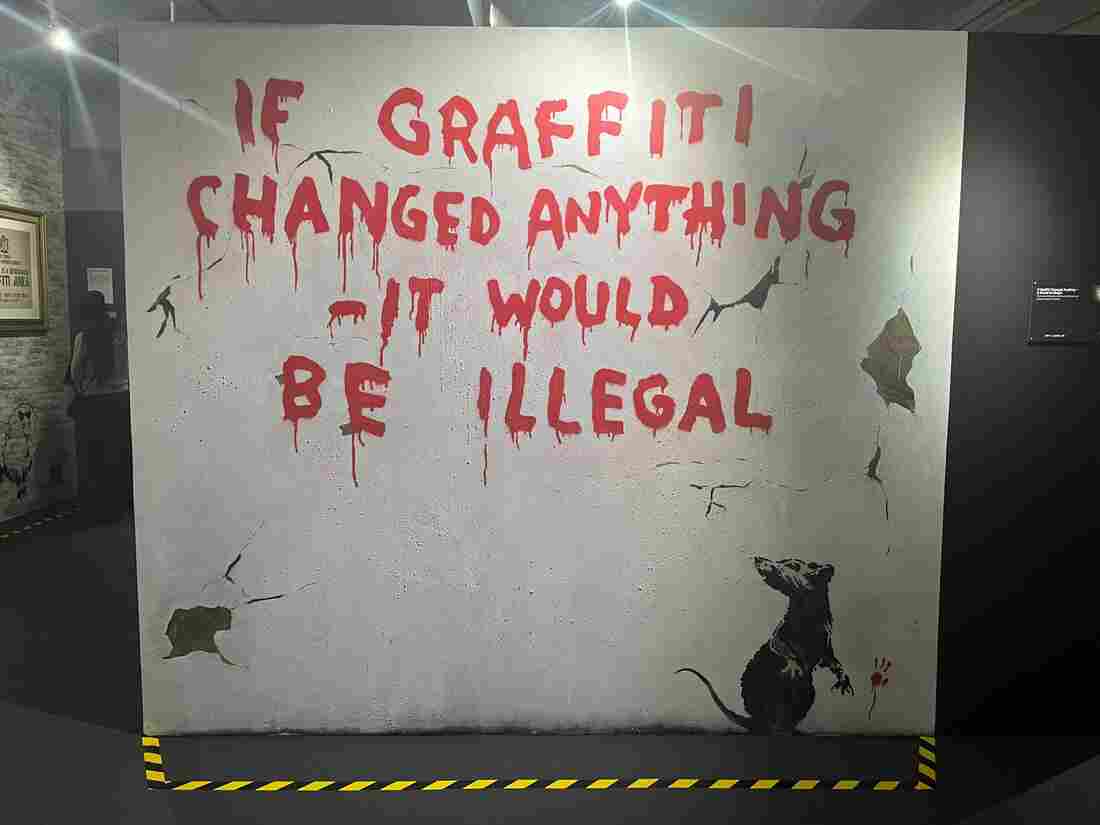

The Banksy Museum’s reproduction of “If Graffiti Changed Anything – It Would Be Illegal”, published in London in 2011.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

The Banksy Museum’s reproduction of “If Graffiti Changed Anything – It Would Be Illegal”, published in London in 2011.

Isabella Gomez Sarmiento/NPR

“The problem is that Banksy never wants to sue because he’s trying to hide his identity, and I think that’s one of the reasons he’s become so popular,” Amineddoleh said. “There is a certain mystique around who he is, and if he destroys that mystique, maybe he would destroy some of the value of his art.”

For now, no lawsuit means the Banksy museum can keep its doors open as long as people show up.

But those visitors won’t include people like Brooklyn Street Art founders Jaime Rojo and Steven P. Harrington. Via email, the men, whose organization preserves and documents street art, said they found the use of the word museum humorous and could not take seriously any Banksy exhibition not authorized by the artist .

“This new iteration is a stretch of considerable credulity, with promoters claiming that anonymous artists in the UK recreated Banksy’s work,” they wrote. “In another field, these people are called commercial artists or decorative painters – it’s no different from recreating Michelangelo’s ‘Creation of Adam’ on the wall of a pizzeria.”

The audio and digital versions of this story were published by Jennifer Vanasco.