The lab, which tests animal samples from across the country, offers a glimpse into how scientists are racing to learn more about the virus, which experts fear could one day evolve to infect more easily humans.

“It’s still an open question, scientifically: what will happen as this virus continues to evolve and spread through animal populations?” » said Runstadler.

On Thursday, Michigan state officials confirmed the third human case of H5N1 in the United States. this year, in a farm worker exposed to infected cows. The worker showed respiratory symptoms, a first for humans exposed to infected cattle, and recovered.

Authorities across the country are on high alert for new cases. Last month, the CDC asked state and local public health officials to maintain their flu surveillance efforts throughout the summer to quickly detect any increases in human illness. The agency also launched a dashboard that tracks influenza A viruses (H5N1 is part of this virus family) in wastewater samples from across the country to identify transmission hotspots .

Runstadler’s work is an important part of this broader surveillance effort. The lab tests a wide range of animals in hopes of detecting cases of H5N1 that might otherwise go unnoticed. One of their concerns is that the virus could make its way to an animal host that shows no symptoms. There, the virus could develop more worrying mutations, such as those that could promote adaptation to mammals.

“These are the places where viruses can evolve and circulate, because no one had their eye on the ball,” said Wendy Puryear, a virologist in Runstadler’s lab.

Avian flu is nothing new to Runstadler and his team. He created his laboratory twenty years ago to study influenza viruses in animals. In 2013, the group began monitoring seals and, in the summer of 2022, became the first to identify and investigate the deaths of more than 180 gray and harbor seals from H5N1 off the coast of Maine.

The seal deaths worried scientists because they were among the first signs that this strain of H5N1 could devastate mammals. Since then, the virus has killed tens of thousands of sea lions and seals in South America and was recently detected in more than 60 dairy herds in nine states.

The laboratory is part of a network of Centers Excellence in Influenza Research and Response, funded by the National Institutes of Health. It’s one of fewer than a dozen network members that do wildlife monitoring and even fewer that do sampling as broadly as Tufts, Puryear said.

The question members of the Runstadler lab are now asking is whether new wild birds and mammals are becoming infected along the East Coast and across the country. The team has tested about 10,000 bird samples and 2,500 mammal samples – including 1,000 from marine mammals – since the virus hit the United States in 2022.

The laboratory regularly detects positive cases of H5N1 in birds, although it has not identified any mammals that have contracted the virus since the seals died in the summer of 2022. The USDA has, however, confirmed cases of avian flu in more than 200 mammals across the country. including foxes, mountain lions, raccoons and bears. The Runstadler lab did not test any cattle, a process that is largely handled by state and federal agencies, Puryear said.

In April, Runstadler went to a Swampscott beach to swab a stranded humpback whale. Although the large mammal tested negative for H5N1, whales have been shown to contract other types of flu.

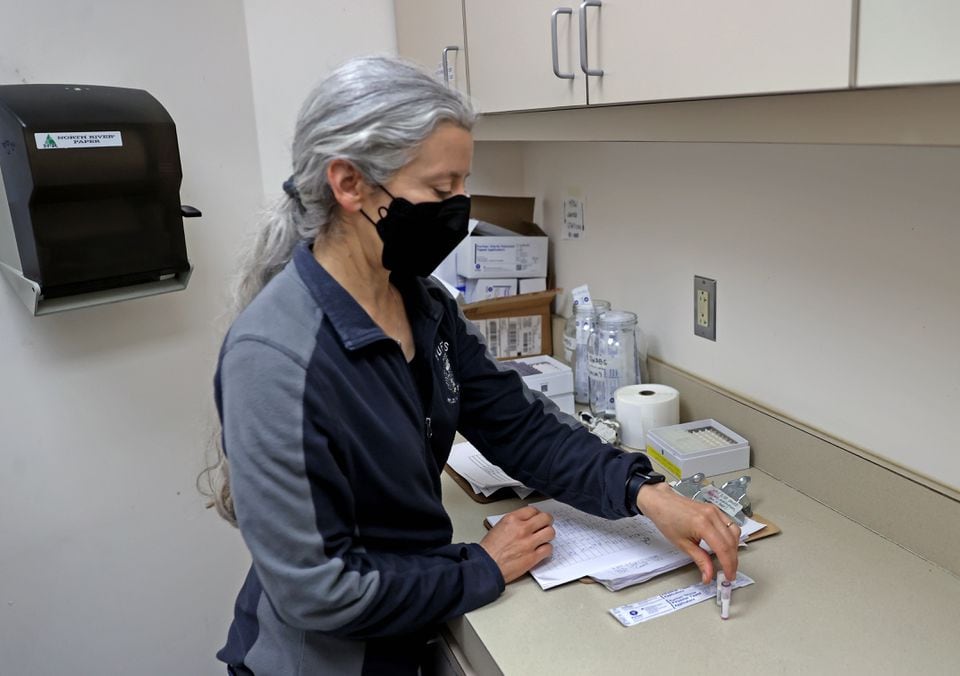

Bird samples are shipped to the lab by collaborators from New England and as far south as Virginia. The marine mammal samples come from Maine as well as Florida, California, Alaska and even Hawaii. Lab members prepare care packages including swabs, personal protective equipment, shipping materials and instructions to help collaborators collect samples safely. Swabs arrive at the laboratory in small screw-cap tubes with a pink-colored liquid which helps preserve the samples. The tubes are placed in Ziploc bags and packed in ice.

When a sample tests positive for H5N1, Puryear and his colleagues notify the person who submitted it to warn them of potential contact with infected animals. They then send the sample to a USDA laboratory for confirmation. The Runstadler lab or a lab at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York then sequences the RNA, or genetic information, of the virus to see if there are any changes in its code. A computer identifies anomalies – such as an “A” in the genetic code changing to a “C” – and the string of letters is uploaded to an online database. There, scientists around the world can access the sequences to determine if and how the virus might evolve.

A concerning mutation, which allows the H5N1 virus to copy itself better inside mammalian cells, was detected in a seal tested by the Runstadler laboratory in the summer of 2022. The mutation, called PB2 E627K, also appeared in several mammals that contracted H5N1 in recent years and, in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier in May, scientists reported that the human who contracted H5N1 in Texas also acquired the PB2 E627K mutation .

Although this mutation is on scientists’ radars, they emphasize that the virus would need additional genetic modifications to promote its spread between humans. In early April, the CDC said the presence of the mutation in a Texas farmworker did not change its assessment that H5N1’s current risk to human health is low.

“I think one of the very valuable things about their work is that it has been continuous over time,” said Ana Silvia Gonzalez-Reiche, a virologist at Mount Sinai who collaborates with the Runstadler lab. “Over the years, they’ve accumulated a lot of data, and the value of that is that you can start to see patterns and learn. »

Puryear and his colleagues don’t always know which samples they will receive in the mail on a given day. On a recent Wednesday around 11 a.m., a delivery man came in with the day’s packages. Puryear grabbed one – a cardboard box with a pet food logo that had been repurposed to transport animal samples – and placed it on the floor. bottom shelf of the refrigerator.

The next day, the team tested the contents of the box. One of the samples, belonging to a Cape Cod crow, tested positive for H5N1.