Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with information on fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and much more..

For more than a century, scientists have searched unsuccessfully for skull fossils of the thunderbird species Genyornis newtoni. About 50,000 years ago, these titans, also known as mihirungs, from an Aboriginal term meaning “giant bird”, roamed the forests and grasslands of Australia on their muscular legs. They were larger than humans and weighed hundreds of pounds.

The last of the mihirungs disappeared around 45,000 years ago. The lone skull, discovered in 1913, was incomplete and badly damaged, raising questions about the giant bird’s face, habits and ancestry.

Now, the discovery of a complete G. newtoni skull has solved this long-standing mystery, giving scientists their first face-to-face encounter with the enormous mihirung.

And he has the face of a very strange goose.

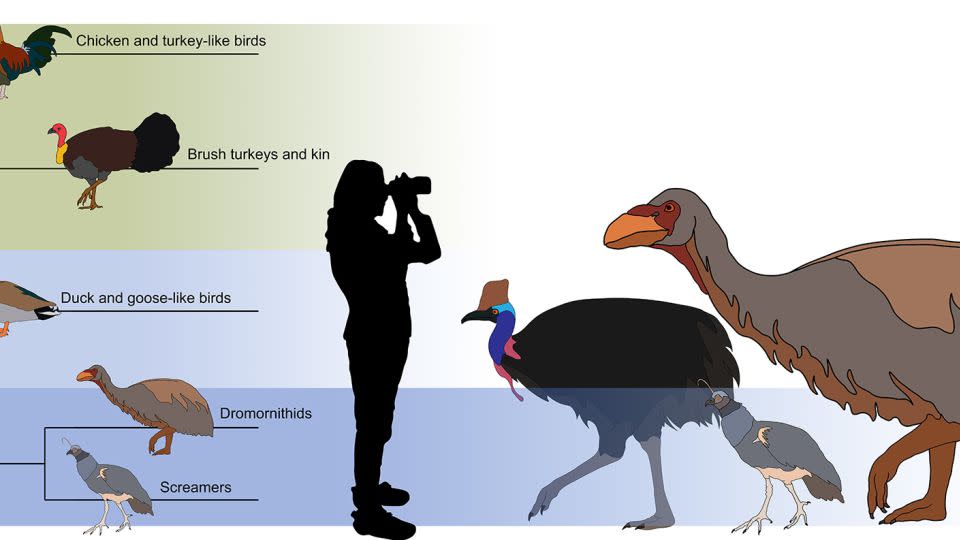

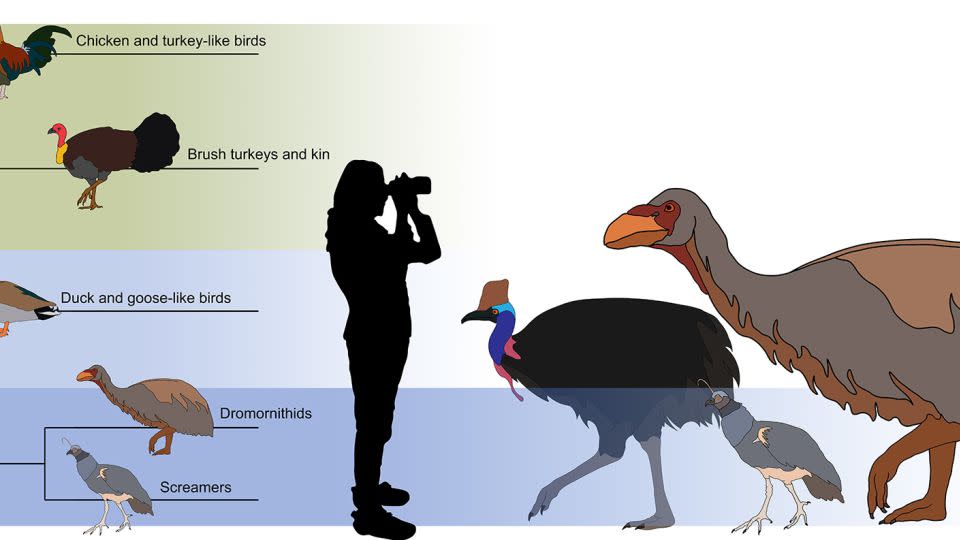

G. newtoni stood about 7 feet (2 meters) tall and weighed up to 529 pounds (240 kilograms). It belonged to the family Dromornithidae, a group of flightless birds known from fossils found in Australia.

Between 2013 and 2019, a team of paleontologists unearthed a jackpot fossil of G. newtoni in Lake Callabonna in southern Australia, discovering several skull fragments, a skeleton and an articulated skull providing the first evidence of the upper beak of the bird. The bonanza shed new light not only on G. newtoni, but also on the entire dromornithid group, linking it to modern waterfowl such as ducks, swans and geese, scientists reported Monday in the journal Historical Biology.

Although scientists have known about Genyornis for more than a century, the new fossils and reconstruction provide critical missing details, said Larry Witmer, a professor of anatomy and paleontology at Ohio State University who did not participated in the research.

“The skull is always the reward, simply because so much important information is in the head,” Witmer said in an email. “It’s where the brain and sensory organs are, it’s where the feeding apparatus is, and it’s usually where the display organs (horns, crests, wattles, and combs) are located , etc.),” he said. “Additionally, skulls tend to exhibit structural features that give us clues about their genealogy.”

In the new study, “the authors exploited these new fossils to the fullest,” Witmer said. The researchers didn’t just model the bones of the skull; they also analyzed the location of jaw muscles, ligaments and other soft tissues hinting at the bird’s biology.

“This latest discovery of new Genyornis skulls has really helped fill in the gaps,” Witmer said.

“Very goose-like”

The newly discovered skull takes center stage in a digital reconstruction, supplemented by other skull fossils and data from modern birds, and it offers previously unknown clues about the appearance of G. newtoni, said the Lead author of the study Phoebe McInerney, a vertebrate palaeontologist and researcher at Flinders University in South Australia.

“Only now, 128 years after its discovery, can we say what it actually looked like,” McInerney said in an email. “Genyornis has a very unusual beak that closely resembles that of a goose.”

Compared to the skulls of most other birds, the skull of G. newtoni is quite short. But the jaws are massive, supported by powerful muscles.

“They would have had a very wide spread,” McInerney said.

The skull also alluded to the diet of G. newtoni. A flat gripping area in the beak was adapted for tearing soft fruit and tender shoots and leaves, and a flattened palate under the upper beak may have been used for crushing fruit into pulp.

“We knew from other evidence that they probably ate soft food, and the new beak confirmed that,” McInerney said. “The skull also showed evidence of adaptations for feeding in water, perhaps on freshwater plants.”

This suggestion of underwater feeding is unexpected, given G. newtoni’s massive size, Witmer said.

“Perhaps this shouldn’t be too surprising given that dromornithids like Genyornis are related to the group including ducks and geese, but Genyornis was six or seven feet tall and weighed perhaps as much as 500 pounds,” he said. Witmer said. Additional fossil discoveries could help determine whether these adaptations were unused traits inherited from aquatic ancestors, “or whether these giant birds were wading through the shallows in search of soft plants and leaves.”

“A strange amalgam”

The reconstruction helped scientists resolve the conflicting lineage of dromornithids, placing them within the waterbird order Anseriformes, the study authors reported. Based on bone structures and associated muscles, dromornithids were likely close relatives of the ancestors of modern South American howlers, duck-like birds inhabiting the wetlands of southern South America.

Although G. newtoni had a goose-like beak, its face did not perfectly match that of modern geese, said study co-author and avian paleontologist Jacob Blokland. A researcher with the Flinders Palaeontology Group at Flinders University, Blokland illustrated reconstructions of the skull and G. newtoni during his lifetime.

“It surprised me how superficially goose-like it looked, with its large spatulate beak, but which looked absolutely nothing like any goose we have today,” Blokland said in an e -mail. “It has some aspects reminiscent of parrots, to which it is not closely related, but also of land birds, which are much closer relatives. In some ways it seems like a strange amalgamation of very different looking birds.

For the new reconstruction, Blokland started with the bony region of the outer ear, “because several specimens preserved that part,” he said. From there, he built a cohesive scaffold for several skull fossils. Some areas of the reconstruction were based on skulls belonging to other dromornithids or modern waterfowl, and anatomical studies of modern birds have hinted at how muscles and ligaments might move bones.

A previously unknown detail was a large triangular bony shield called a helmet on the upper beak, which may have been used for sexual displays, the study authors reported.

Large flightless emus and cassowaries (which are not close relatives of thunderbirds) currently roam Australia, but cast a much smaller shadow than the long-lost mihirungs, which still feature prominently in the popular imagination, McInerney said. There is much to discover about the anatomy of these extinct giants, she added, such as how inner ear structures associated with head stabilization and locomotion might have been affected by gigantism and inability to fly.

And while the new perspective on G. newtoni is the most accurate yet, additional fossils will sharpen the portrait of this unusual gargantuan goose — the last of the mighty thunderbirds — and its extinct habitat, Blockland said .

“Such a giant and unique bird undoubtedly affected the environment and other animals it interacted with, large or small,” he said. “Only through study can we paint a broader picture and find out what we are currently missing. »

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works magazines.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com