After more than six months of grueling negotiations, David Ellison thought he was on the verge of closing the deal of his life: taking over Paramount, the century-old Hollywood studio.

Ellison received news Tuesday morning in Los Angeles from an adviser to Shari Redstone, the heiress who controls the media group behind classics including The Godfather, Chinese district And Titanic, that all the financial details of the agreement had been settled. At a meeting Tuesday at 2:30 p.m. (New York time), Paramount’s special committee planned to greenlight the proposal from Ellison’s company, Skydance Media.

And then came the plot twist. Minutes before independent advisers evaluating Skydance’s offer recommended it, Redstone’s lawyers, Ropes & Gray, sent a brief email to the board’s special committee saying the deal was dead. “While it is true that we agree on all important economic terms, there are other terms outstanding and we are fundamentally moving backwards,” the message said, according to a person with knowledge of the matter, who paraphrased its contents .

“Shari effectively killed a deal that had been fully negotiated, fully concluded on all key economic aspects, two minutes before the special committee meeting,” the person added. “That was it.”

It was an abrupt and bitter end to a story in which the two protagonists had formed an unlikely bond. Both are the children of billionaire fathers: Redstone, 70, is the daughter of Sumner Redstone, who built the media and entertainment empire that is at the heart of Paramount – a group that also includes the CBS television network, MTV, Comedy Central. and Nickelodeon. Ellison’s father, Larry, is the billionaire co-founder of Oracle, the software company.

David Ellison also has a deep connection to Paramount, having produced a number of blockbusters alongside the studio, including Top Gun: Maverick.

But in recent weeks, their bond weakened as they argued over the details of the deal — and speculation swirled that Redstone had second thoughts about abandoning the family business. When it was all over, exasperated councilors said they couldn’t remember a more complicated process. And observers from Wall Street to Hollywood were wondering what Redstone’s next move would be.

Paramount offered Ellison a rare opportunity to take control of one of Hollywood’s crown jewels, rich in history with its iconic land on Melrose Avenue and century-old film library.

The studio struggled to adapt to the digital age, but Ellison, 41, believed he could solve the group’s growing problems. Its once-powerful, generation-defining television channels, such as MTV, are in long-term decline while streaming service Paramount+ is losing money.

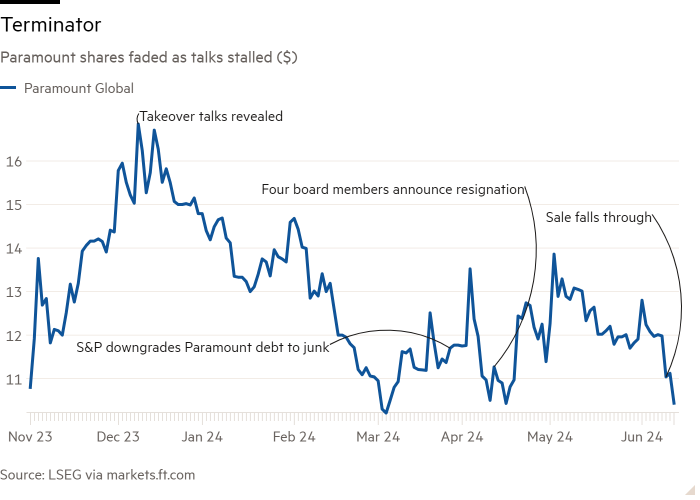

Paramount, valued at less than $8 billion on the stock market, has more than $14 billion in debt, which was recently downgraded to junk securities. Investors have lost confidence in the company’s ability to compete on its own, making it the subject of takeover speculation for several years. Shares have fallen 30 percent this year, including a nearly 15 percent drop since trading was called off.

The deal was never going to be easy to close. Ellison’s plan had two steps: First, his company would buy National Amusements (NAI), the Redstone-controlled group that owns 77 percent of Paramount’s voting stock. Next, Paramount would acquire Skydance in a stock transaction.

The first cracks appeared in May when Ellison’s consortium, which included private equity groups RedBird and KKR as well as his family’s fortune, adjusted its offer after it became clear that Paramount’s common shareholders planned to retaliate. Several holders of Paramount’s non-voting shares have publicly threatened legal action if the deal goes through, saying all the value would go to Redstone, which owns the majority of the voting shares.

So Ellison’s team decided to pay NAI – and by extension, Redstone itself – less than what was initially offered to sweeten the deal for Paramount’s B shareholders.

After Skydance decided in May to reduce its offer to NAI from $2.5 billion to $2.3 billion, including debt, Redstone stopped talking with Ellison, people briefed on the matter said. Others involved said the decision to stop communication was out of respect for the negotiating process with the special committee. These people added that NAI ultimately accepted the lower offer of $2.3 billion.

Nonetheless, Redstone had begun to lose confidence in Ellison following the adjusted offer, those close to him said. The same people added that despite Redstone’s changing perception of Ellison, the Skydance founder was well respected by NAI and Paramount advisors for his integrity throughout the process.

Only after Ellison learned the deal was dead did Redstone inform him she was upset about the reduction in the cash offer for her stake, a person close to her said . “She was upset she didn’t get more,” the person said.

Others close to Redstone disputed that claim, saying the deal fell through because Ellison’s camp resisted calls to allow non-voting shareholders to record their “consent” — or lack thereof – to the transaction by a sort of countdown. “Obviously it would have provided protection against shareholder litigation,” said another person familiar with Redstone’s thinking.

People close to Skydance and Paramount said Redstone decided to use the “consent” vote as a last-minute excuse to scupper the deal; the issue had been settled from the start of the negotiations.

There were other signs of friction as Redstone continued the sale. In April, Redstone fired its longtime chief executive, Bob Bakish, who had made no secret of his opposition to the Skydance deal and continued discussions with other potential suitors. She replaced Bakish with three Paramount executives who formed a “CEO office.” Four board members also left this spring.

Throughout the process, other potential bidders came and went. Paramount’s shares fell in December when it emerged that Bakish had met with his Warner Bros. Discovery counterpart, David Zaslav. Private equity group Apollo approached Paramount twice, the last time with Sony as a partner. And this week, Edgar Bronfman Jr, the heir to Seagram, made a move alongside Bain Capital.

Several people directly and indirectly involved in the process said it wasn’t just money that persuaded Redstone to walk away from a deal with Ellison that she made months ago.

Several people said Redstone couldn’t move on from a company founded by her grandfather and transformed into a global force by her father, with whom she had a strained relationship.

Redstone appears to have welcomed the turnaround plans drawn up by the three members of the CEO’s office – a group that many expected would be mere placeholders until the Skydance deal was completed. But last week they unveiled a plan to cut costs and reorganize the group, and she gave them her blessing.

“If all Skydance wants to do is reduce company costs and streamline the streaming business, we could just do it ourselves without risk of litigation and without 12 to 18 months (to get) to closing,” said a person familiar with the matter. strategy.

Some investors, however, seem disconcerted by this idea. “This might be acceptable as an interim model,” said John Rogers, president and co-CEO of Ariel Investments. “But I haven’t experienced anything where you had a long-term agreement with three leaders. It’s just not normal.

Several people, including current and former board members, said another factor working against Skydance was the role played by Charles Phillips, a Paramount board member who tried to torpedo the company. agreement throughout the process.

Phillips, who worked at Oracle until 2010, was against the deal and spoke out against it frequently, current and former Paramount board members said. He did so by throwing up numerous obstacles to a deal with Skydance and speaking negatively about the Ellison family to Redstone, the sources said.

A number of people involved in the process said Phillips should have recused himself from the process because he was personally against the Ellison family because of their history. Phillips did not immediately respond to a request for comment; a person close to the board disputed that assertion, saying he “has deep respect for the Ellisons.”

In the other direction, another Oracle veteran: Larry Ellison himself, who became more involved as the negotiations drew to a close. Some members of Redstone’s camp have pointed to Larry Ellison’s involvement as a reason tensions have increased over the past week. “The more Larry gets involved, the worse the relationship gets,” said a person familiar with the matter. “There was a leaning towards David, but Larry has a sharper elbow.»

Another person involved in the deal negotiations dismissed those concerns. “Larry was obviously involved,” he said. “Larry was writing a big check.”

Regardless of the tensions, David Ellison thought he was going to sign a deal to acquire Paramount this week. “Everything has been resolved,” said one person involved.

Like a classic Hollywood cliffhanger, the collapse leaves Redstone in a bind with no obvious way out. Paramount is a small, struggling company drowning under a mountain of debt, and its stock price is plummeting. His family’s wealth is strained by the financial pressures of his father’s death. And NAI has its own debt burden. Yet even after months of negotiations, people close to Ellison’s offer say they’re not sure what motivated Redstone to pull the plug.

“In the end, (maybe) she got to the finish line and decided she couldn’t sell her inheritance,” one said.