The new main exhibition hall at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, June 14, 2024.

Jared Soares for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jared Soares for NPR

Washington, D.C.’s Folger Shakespeare Library — home to the world’s largest Shakespeare collection — is emerging from a four-year metamorphosis that has left it almost entirely transformed — new museum spaces, new direction announced, new programming.

After being restricted to scholars for years, the jewels of the library’s collection – 82 copies of Shakespeare’s “First Folio,” printed 400 years ago – will now be put on public display for the first time.

We got a behind-the-scenes look at how the Folger is reaching new audiences.

Shakespeare and the Classics at Chocolate City

So much has changed at the Folger Shakespeare Library since it closed for renovations in January 2020, that it makes sense that the show reopening its performance space is called Metamorphoses. Mary Zimmerman’s adaptation of Ovid’s epic Roman poem is about change, and Karen Ann Daniels, who directs programming at the Folger and is artistic director of its theater, felt she could speak to underserved audiences about Washington if the Folger Theater did things right.

“The play could really draw on the broader history of the people of D.C.,” she said. “I totally think Chocolate City. That’s really where my idea came from.

His idea was to perform the play with an all-black cast, an idea that director Psalmayene 24 wasn’t sure he agreed with until Memphis police officers fatally injured Tire Nichols, a black employee of FedEx, last year during a traffic stop. The director said he overcame his grief over the incident by incorporating elements of the black diaspora into Metamorphoses to celebrate black humanity.

“The play could really draw on the broader history of the populations of D.C.,” said Karen Ann Daniels, artistic director of the Folger Theater, shown here in the Folger’s performance space on June 14, 2024.

Jared Soares for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jared Soares for NPR

“So in a way this piece is a response to America’s own propensity to be murderously anti-black,” he said. “And when you do a show like this at a place like Folger, it says something about how not only is the Folger Theater changing, but how American culture is changing, how DC is changing and how the stories that run through this theater are truly universal. These stories are for everyone and can be told in different ways.

The librarian has a favorite first folio. It’s not the fanciest.

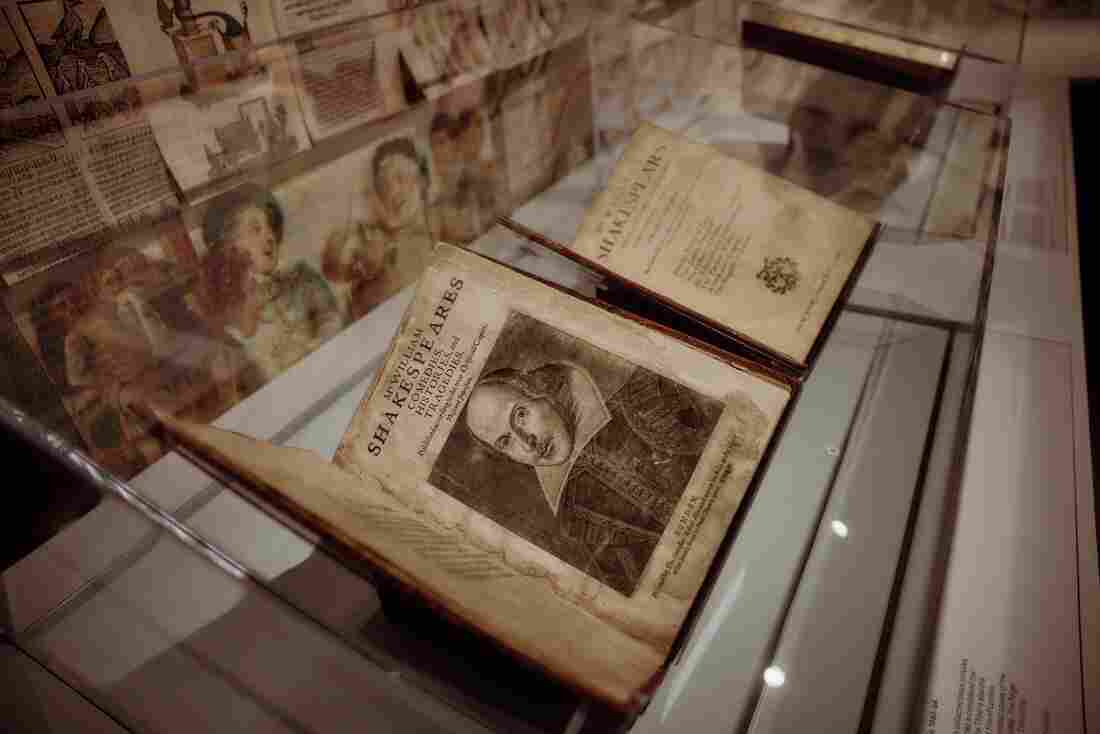

A huge display case in the middle of the library’s new exhibition space glows softly, quietly announcing that it contains the library’s crown jewel: 82 copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio printed in 1623, more than a third of all copies known.

The First Folio marked the first time, just a few years after Shakespeare’s death, that his works were collected in a single volume, making it a reference for scholars. But no two copies collected by Henry and Emily Folger over the course of their lives are alike. Some are skinny, others massive.

One of 82 copies in the Folger Shakespeare Library First Folio, the bard’s complete works printed in 1623, just a few years after his death.

Jared Soares for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jared Soares for NPR

“These were all printed in 1623,” confirmed Greg Prickman, Folger librarian and collections director, “in the printing press of William Jaggard and his son Isaac, but over the next 400 years many things have happened to these books. Sometimes they are damaged and parts are removed. Sometimes parts are added from other copies.

Asked if he had a favorite, he walked to the far right of the display case, past some beautifully leather-bound Folios with gold tooling.

“The one I like the most is number 30 – the only copy in this collection that has the original binding that was put in place when I first purchased this book, shortly after it was printed.

“So if you wanted to see, ‘What does Shakespeare’s first folio look like when it was just a new book in quotes?’ This is the copy you’re going to look at, it’s number 30.”

A sample of Shakespearean insults

To the right of the main window is a smaller interactive screen that allows you to create a Shakespearean conversation. We only spent a few moments there, but the screen makes its own selection from phrases from the Bard’s plays once you choose a category – perhaps “blessing” (“You are born nobly”) or “burning” (“Do as you were born”). will wither, for I have finished with you”).

We only played with this for a few minutes, but we note that the plays contain a full complement of Shakespearean insults, so in theory it could lead you to hurl Elizabethan invectives such as:

“Away, rag, quantity, stay. » (Taming the shrewAct 4, scene 3)

“I feel sick when I look at you.” (A Midsummer Night’s dreamAct 2, scene 1)

“I must whisper in your friendly ear: Sell when you can; you are not for every market. (As you like it, Act 3, scene 5)

“More of your conversation would infect my brain.” (CoriolanusAct 2, scene 1)

“The most odious compound of vile odor that ever offended the nostrils.” (The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 3, scene 5)

“And you are unfit for any place other than hell.” (Richard III, Act 1 scene 2)

“Bad guy, I made your mother.” (Titus Andronicus, Act 4, scene 2)

“Would you be clean enough to spit on it!” » (Timon of AthensAct 4, scene 3)

The enigma of the mulberry tree

The exhibition space features many rare manuscripts in a room called “Out of the Vault,” which of course made us wonder what else was there. In “the safe”, which is not open to the public. So we asked, and were led up a flight of stairs to an imposing steel vault door, behind which are the stacks of refrigerated bookcases (“because it makes the books happy”) containing the quarter million other volumes from the Folger collection. .

There are also 100,000 objects here, ranging from paintings of the bard to props, costumes, models and “tree pieces,” Prickman said enigmatically.

Librarian Greg Prickman is the director of collections and exhibitions at the Folger.

Jared Soares/Jared Soares for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jared Soares/Jared Soares for NPR

“The mulberry tree,” he continued when pressed. “‘Objects associated with Shakespearean legends’ is probably the best way to put it. I’m not the one telling this story.

So we looked for it.

Shakespeare is said to have planted a mulberry tree at his home in Stratford. More than a century later, in the 1750s, the Rev. Francis Gastrell, then owner of the house, was so tired of people asking him to see it that he cut it down, and local contractor Thomas Sharpe bought the wood and turned it into Shakespearean memorabilia. — everything from a carved coffin that was given to actor David Garrick (1717-1779), to snuff boxes and medallions.

So many objects were created that they clearly didn’t all come from the same tree, but the Folger has a few.

Why the Folgers bet on the humanities

The impulse to reach a more universal audience is what led Folger Library Director Michael Witmore to lead the library’s $80.5 million overhaul — a comprehensive “makeover” , if you will, of a building and a mission that, frankly, worked pretty well.

“During the early part of the Folger’s existence, it was primarily a research library,” Witmore said, “serving scholars who studied everything from animal husbandry to lyric poetry to theater. But we have the facilities and collections to do more, and this renovation allows us to take a world-class research library and surround it with a cultural institution that is a destination.

A destination serving words written more than 400 years ago. Words that are also available digitally: “We digitize in order to create access,” Prickman said, “and we expose materials in order to create access.” The originals remain.”

And having those originals right next to the Library of Congress, the U.S. Capitol and the Supreme Court was a big part of Henry and Emily Folger’s intent, Witmore said.

A view of the new underground entrance to the Folger Shakespeare Library’s exhibition spaces.

Jared Soares for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jared Soares for NPR

“We need these words and these stories to elevate our sense of what is possible as citizens. When you think about what’s happening at the Capitol, that’s where the words – you may not agree with them, you may think they’re funny or superficial – but that’s where words really matter. Including when the court examines the meaning of these words.

“So putting a Shakespeare library where his works are performed and people work on the poems and other things, right in this location, I think, is a big bet on the importance of the humanities and the arts in a functioning democracy.

Story edited and produced in the field by Jennifer Vanasco. Broadcast report produced by Isabella Gomez Sarmiento.