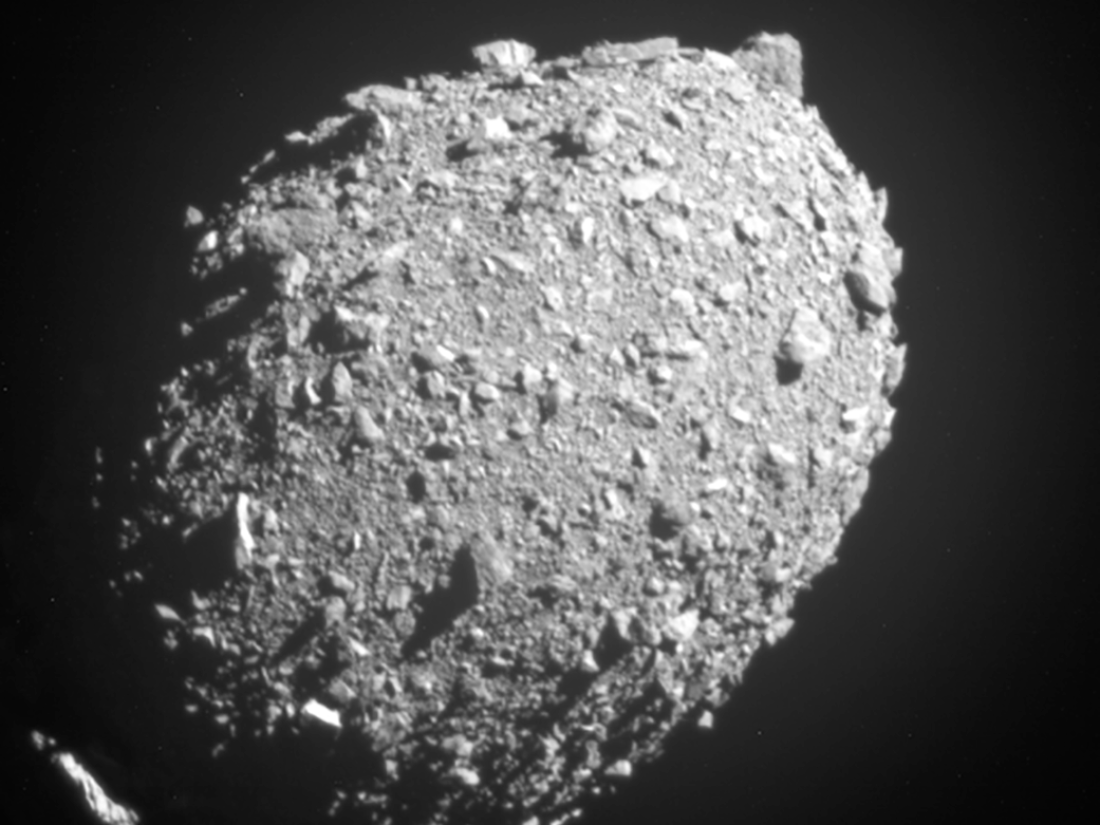

The moon of the asteroid Dimorphos as seen by NASA’s DART spacecraft 11 seconds before the impact that changed its trajectory through space, in the first test of an asteroid’s deflection.

Johns Hopkins University/NASA Applied Physics Laboratory

hide caption

toggle caption

Johns Hopkins University/NASA Applied Physics Laboratory

Imagine if scientists discovered a giant asteroid with a 72 percent chance of hitting Earth in about 14 years — a space rock so big it could not only destroy a city but devastate an entire region.

This is the hypothetical scenario that asteroid experts, NASA employees, federal emergency management officials and their international partners recently discussed as part of a tabletop simulation designed to improve the nation’s capacity to respond to future asteroid threats, according to a just-published report. by the space agency.

“Right now, we don’t know of any asteroids of substantial size that are likely to hit Earth in the next hundred years,” says Terik Daly, supervisor of the planetary defense section at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, in Maryland.

“But we also know,” says Daly, “that we don’t know where most of the asteroids large enough to cause regional devastation are.”

NASA experts and federal emergency management officials face a hypothetical asteroid threat in April 2024.

Ed Whitman/NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

hide caption

toggle caption

Ed Whitman/NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

Astronomers estimate that there are about 25,000 of these “near-Earth objects” measuring 140 meters in diameter or larger, but only about 43 percent have been discovered to date, according to materials prepared for the tabletop exercise held in April in Laurel. , MD.

The event was just the latest in a series of exercises that planetary defense experts have held every two years to practice handling news of a potentially planet-threatening asteroid — and it is the first since NASA’s DART mission, which showed that ramming a spacecraft into an asteroid could change its trajectory through space.

This time, just after the discovery of the fictional asteroid, scientists estimated its size between 60 meters and almost 800 meters in diameter.

Even an asteroid at the smaller end of this range could have a big impact, depending on where it hits Earth, says Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer emeritus.

Although “a 200-foot asteroid hitting somewhere in the middle of the ocean” wouldn’t be a real problem, he said, the same asteroid hitting land near a metropolitan area would be “a serious situation.”

Since telescopes would see such an asteroid as just a bright point in space, Daly explains, “we’re going to have very large uncertainties about the properties of the asteroid, which leads to very large uncertainties about the consequences” it was destroyed. hitting the ground, as well as great uncertainty about what it would take to stop this asteroid from hitting the ground.

Additionally, this particular scenario disturbingly stipulated that scientists would not be able to learn more about this threat for more than six months, when telescopes would be able to spot the asteroid again and make another assessment of its path.

Exercise participants discussed three options: simply wait and do nothing until the next telescope observations; launch a U.S.-led space mission for a spacecraft to fly by the asteroid to obtain more information; or create an effort to build a more expensive spacecraft that would be able to spend time around the asteroid and perhaps even change its trajectory through space.

Unlike previous asteroid threat simulations, this one did not end dramatically. “In fact, we were stuck at one point during the entire exercise. We didn’t move quickly,” says Daly.

As a result, participants had plenty of time to discuss how to communicate both uncertainties and the urgent need for action. They also discussed how funding and other practical considerations might play a role in the decision-making processes of federal agencies and Congress.

Daly says that in previous discussions, technical experts tended to assume that access to financing would not be an issue in such an unprecedented situation, but “the reality is, absolutely, that cost was a concern and a factor “.

NASA’s report on the exercise notes that “many stakeholders expressed that they would like to have as much information about the asteroid as soon as possible, but expressed skepticism that funding would be available to obtain such information without more definitive knowledge of the risk. »

While representatives of space institutions clearly preferred to act quickly, “what would political leaders actually do? Daly said. “It was really an open question that persisted throughout.”

Preparing some kind of spacecraft, finding the right launch window and flying it through space to an asteroid “takes a decade pretty quickly,” Johnson says. “So it’s definitely a concern, looking at it from a technology perspective.”

But about 14 years’ notice will seem like a lot of time to emergency managers and disaster responders, says Leviticus “LA” Lewis, a Federal Emergency Management Agency employee tasked with working with NASA.

Lewis notes that emergency managers should think about devoting resources to this seemingly distant threat while responding to more immediate dangers like tornadoes and hurricanes. “It’s going to be a particular challenge,” he said.

Meanwhile, NASA is set to launch a new asteroid-searching telescope in fall 2027, Johnson said.

“We need to find out what’s out there, determine their orbits, and then determine whether they pose an impact risk to Earth over time,” he says.