|

You only have a minute? Listen instead |

OhThe trajectory of a person’s life can often be changed by a single moment. A moment that is sometimes overlooked when it happens but ends up being the decision that changes everything.

For Dr. Roberto Manllo-Karim, a native of Monterrey, Mexico, that moment happened when he was just 15 years old at Tecnológico de Monterrey, the university he attended, and ultimately led him to make a discovery that saved lives.

During their “information day,” a time when people talk about career paths, Manllo-Karim — a physician at South Texas Kidney Specialists in McAllen — found himself waiting in line for engineering.

“I was supposed to be an engineer like my brother or a businessman like my father, but the line was too long,” Manllo-Karim said with a laugh Thursday. “The medical school had just opened the year before, so there was no one in the medical school queue. I’m 15, I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, so I went in and talked to the doctor that was in the medical school.

It was this decision that led him on the path to medicine.

Although he was attending medical school at the university at the time, he was still interested in engineering and so chose to take computer programming courses.

It was these courses that led him to the University of Kansas where he studied pharmacology, the science of developing new drugs using computers.

At the age of 17, he spent the summer in Kansas where he helped write computer programs to teach pharmacology.

“That’s when I met some of my mentors,” Manllo-Karim said. “I fell in love with pharmacology. I said that’s what I wanted to do, I wanted to create new knowledge.

He loved pharmacology so much that he told the president he wanted to leave medical school.

He also remembers the president mocking him and telling him to finish his medical degree and write him a letter once he was done because he would allow him to move on to his doctorate as soon as he would have finished.

That’s exactly what he did.

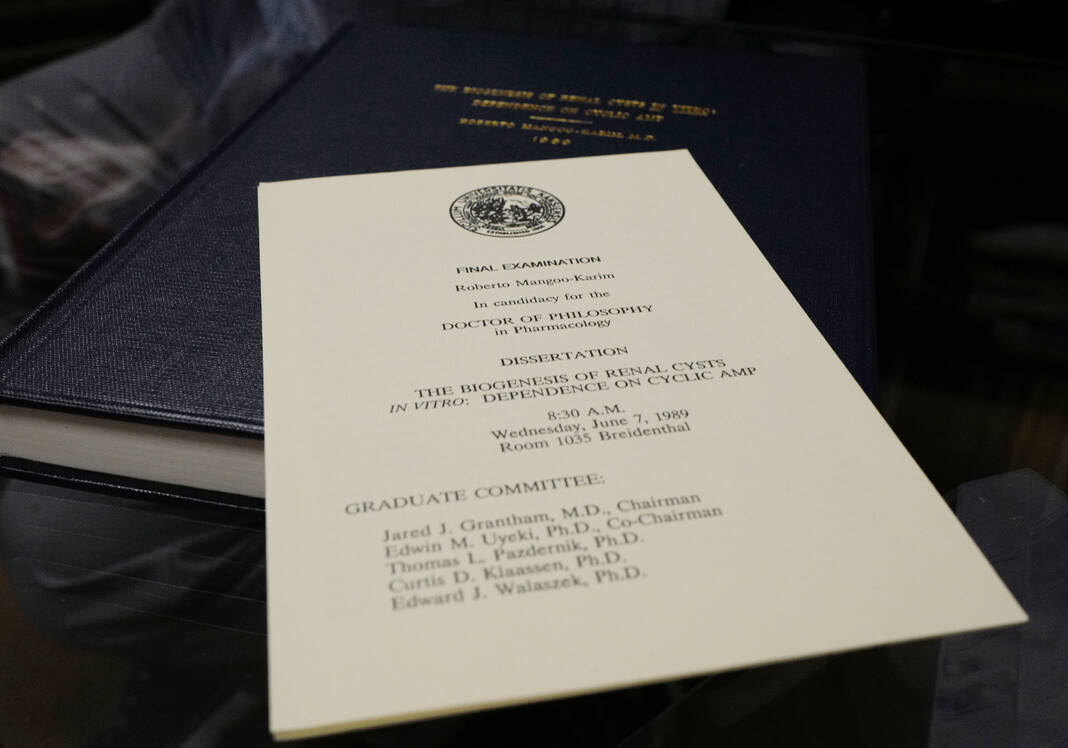

Throughout his graduate studies, he focused his efforts on understanding polycystic kidney disease, a disease that affects half a million people in the county and the fourth leading cause of kidney failure requiring dialysis.

He remembers his mentor, Dr. Jared Grantham, telling him that if he wanted to graduate, he needed to write three papers telling the story of how cysts develop in the kidneys.

“My mentor told me, ‘Roberto, if there’s no story to tell, I’m not going to let you graduate,’” Manllo-Karim said. “He said ‘make me a cyst, I don’t care if it has anything to do with medicine, I just need to know how to make a cyst.’ If you do this, you graduate. If you don’t do it, you don’t do it.

Even though the challenge scared him, it pushed him to find a solution.

“No one knew. We had no idea where this disease came from,” Manllo-Karim said.

He remembers spending up to 16 hours a day, every day, researching the disease and its potential source.

“I opened the library every day for about a month…I was the first in line. The librarian hated me,” Mangllo-Karim laughs, remembering how many newspapers he read.

By the end of the day, he accumulated about 40 to 50 books, and since he was usually the last to leave, the librarian was left with the task of returning them.

She may have hated him for it, but in the end he said it paid off.

Through his research, he discovered that cyclic adenosine monophosphate, or cAMP, caused the cysts to enlarge and continue to develop.

By continuing his research, he was able to find a way to prevent or delay the development of the disease.

He remembers the day he presented his thesis to his mentor and colleagues.

“Monday (at) 8 a.m., meeting with my mentor, of course the seniors start talking first, I’m the junior, and I start giving all this information (very quickly) to the point where he couldn’t “I don’t understand,” says Manllo-Karim, laughing.

He remembered his mentor, incredulous, saying that in three months Manllo-Karim had managed to discover the cause of the disease and its treatment.

After running three follow-up tests to prove his thesis, it was finally ready for publication, or so he thought.

He gathered his thesis and photos and left them on his mentor’s desk.

To his surprise, the next day he saw the thesis in red ink on his desk asking him to redo it. He went back and forth for a while until he couldn’t find any more things to change.

“One day I went to him and said, ‘Dr. Grantham, this is the best I can do.’ Do you know what he told me? “OK, I’ll read this one,” Manllo-Karim said, adding that that’s when he realized he had never read the previous copies.

After submitting it for publication, it was accepted as is.

“It was a work of art above science,” he said.

His work was published in 1989.

“The only treatment available today is based on this (his thesis),” Manllo-Karim said, adding that 25 years later the drug became available.

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. developed a drug called Tolvaptanalso known by the brand name JYNARQUE and others, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018 as the first treatment to slow the decline of kidney function in adults at risk for autosomal polycystic kidney disease dominant (PKD) with rapid progression.

Not bad for someone who opened his lab in a closet, as he described it. But once his thesis was completed, he gained credibility and his work grew from a small laboratory to an entire floor.

There are now two buildings dedicated to polycystic kidney disease, with the University of Kansas being the leading researcher in the area, he said.

It also means he was able to help his loved ones.

Take a friend who has polycystic kidney disease and whose family has lost loved ones to the disease. This friend became Manllo-Karim’s first research patient.

“We cried several times because he was worried about having children with the gene,” the good doctor said.

His friend agreed to the clinical trial before the drug was available and he has been participating in it for over a decade now.

As a result, his kidneys function the same as they did 10 years ago, even though he lives with a disease that otherwise would have required him to be on dialysis now.

“…He is very grateful,” the doctor said of his friend.

This unexpected journey into medicine introduced him to people he met along the way who he considers a blessing to him.

He keeps each of his mentors close to his heart with photos of them and their accomplishments adorning his office walls, desks and even on his floor.

“That’s what success is in life: surround yourself with the best people, ask for advice, work hard and it all happens,” Manllo-Karim said with a smile.

He explained that he was grateful to have faced these challenges and the impact it had on his life.

“It’s a blessing, I can’t tell you how honored I was to be able to come up with a good idea that helps humans today,” he added. “I never expected to achieve something so relevant.

“I made my father proud. Isn’t that what we all ultimately want to do?