Fifty years ago, scientists discovered a nearly complete fossilized skull and hundreds of pieces of bone from a 3.2 million-year-old female specimen of the genus. Australopithecus afarensis, often described as “the mother of us all”. In a celebration following her discovery, she was named “Lucy”, after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”.

Although Lucy has solved some evolutionary puzzles, her appearance remains an age-old secret.

Popular renderings dress it in thick reddish-brown fur, with its face, hands, feet, and breasts poking out from the denser thickets.

Turns out that hairy photo of Lucy might be fake.

Technological advances in genetic analysis suggest that Lucy may have been naked, or at least much more finely veiled.

According to the co-evolutionary history of humans and their lice, our immediate ancestors lost most of their fur 3 to 4 million years ago and did not gain clothing until 83,000 to 170,000 years ago. years.

This means that for over 2.5 million years, early humans and their ancestors were simply naked.

As a philosopher, I am interested in how modern culture influences representations of the past. And the way Lucy has been depicted in newspapers, textbooks, and museums may say more about us than it does about her.

From nudity to shame

Hair loss in early humans was likely influenced by a combination of factors, including thermoregulation, delayed physiological development, attraction to sexual partners, and protection from parasites. Environmental, social, and cultural factors may have encouraged the eventual adoption of clothing.

Both areas of research – on when and why hominids shed their hair and when and why they eventually became clothed – focus on the sheer size of the brain, which takes years to nourish and requires a disproportionate amount of energy to maintain itself in relation to other parts of the brain. the body.

Because human babies require a long period of care before they can survive on their own, interdisciplinary evolutionary researchers have hypothesized that early humans adopted the pair bonding strategy – a male and female pairing up after having formed a strong affinity for each other. By working together, the two can more easily manage years of parental care.

However, pair bonding comes with risks.

Because humans are social and live in large groups, they are inevitably tempted to break the pact of monogamy, which would make raising children more difficult.

A mechanism was needed to guarantee the social-sexual compact. This mechanism was probably a shame.

In the documentary “What’s Wrong With Nudity?” » Evolutionary anthropologist Daniel MT Fessler explains the evolution of shame: “The human body is a supreme sexual advertisement… Nudity is a threat to the fundamental social contract, because it is an invitation to defection… Shame encourages us to remain faithful to our partners and to share. the responsibility of raising our children.

Boundaries between the body and the world

Humans, aptly described as “naked apes”, are unique due to their lack of fur and their systematic adoption of clothing. It was only by banning nudity that “nudity” became a reality.

As human civilization developed, measures had to be put in place to enforce the social contract – punitive sanctions, laws, social dictates – particularly with regard to women.

This is how the relationship of shame to human nudity was born. To be naked is to violate social norms and regulations. Therefore, you tend to feel ashamed.

What is considered naked in one context, however, cannot be considered naked in another.

Bare ankles in Victorian England, for example, caused scandal. Today, bare tops on a French Mediterranean beach are commonplace.

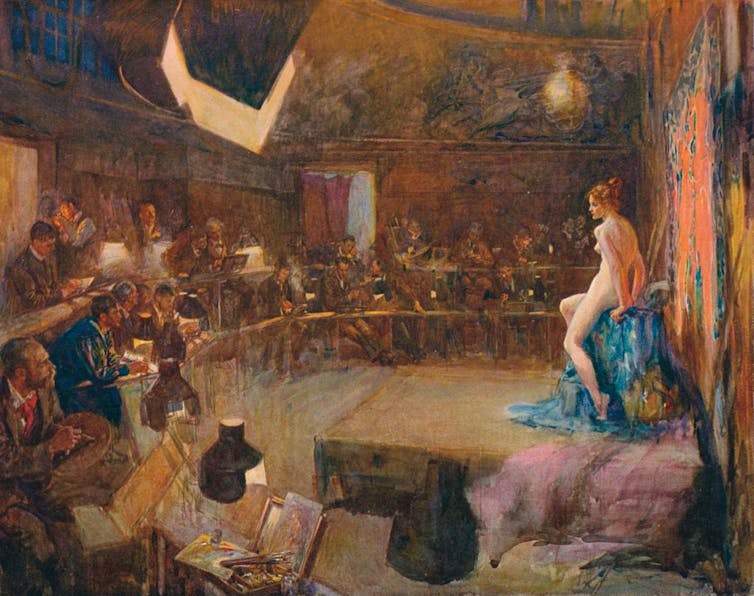

When it comes to nudity, art doesn’t necessarily imitate life.

In his critique of the European tradition of oil painting, art critic John Berger distinguishes between nudity – “being oneself” without clothing – and the “nude”, an art form which turns a woman’s naked body into a pleasing sight for men.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

Feminist critics such as Ruth Barcan have complicated Berger’s distinction between nudity and the nude, insisting that nudity is already shaped by idealized representations.

In “Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy,” Barcan demonstrates how nudity is not a neutral state but is fraught with meaning and expectations. She describes the “feeling of nakedness” as “the increased perception of temperature and air movement, the loss of the familiar boundary between the body and the world, as well as the effects of the real gaze of others” or “the internalized gaze of an imagined other.” »

Nudity can arouse a range of feelings – from eroticism and intimacy to vulnerability, fear and shame. But nudity does not exist outside of social norms and cultural practices.

Lucy’s sails

Whatever the density of her fur, Lucy was not naked.

But just as the nude is a kind of dress, Lucy, since her discovery, has been presented in a way that reflects historical assumptions about motherhood and the nuclear family. For example, Lucy is depicted alone with a male companion or with a male companion and children. Her facial expressions are warm and content or protective, reflecting idealized images of motherhood.

The modern quest to visualize our distant ancestors has been criticized as a kind of “erotic fantasy science,” in which scientists attempt to fill in the blanks of the past based on their own assumptions about women, men, and their relationships. with each other.

In their 2021 paper “Visual Depictions of Our Evolutionary Past,” an interdisciplinary team of researchers tried a different approach. They detail their own reconstruction of the Lucy fossil, highlighting their methods, the relationship between art and science, and the decisions made to fill gaps in scientific knowledge.

Their process contrasts with other hominid reconstructions, which often lack strong empirical justifications and perpetuate misogynistic and racialized misconceptions about human evolution. Historically, illustrations of the stages of human evolution have tended to result in a white European male. And many reconstructions of female hominins exaggerate offensive characteristics associated with black women.

One of the co-authors of “Visual Depictions,” sculptor Gabriel Vinas, offers a visual explanation of the reconstruction of Lucy in “Santa Lucia” – a marble sculpture of Lucy in the form of a nude figure draped in a translucent fabric, representing the artist’s own and Lucy’s insecurities. mysterious appearance.

Veiled Lucy is about the complex relationships between nudity, covering, sex and shame. But it also presents Lucy as a veiled virgin, a figure revered for her sexual “purity.”

And yet I can’t help but imagine Lucy beyond the fabric, a Lucy neither in the sky with diamonds nor frozen in maternal idealization – a Lucy going “Apeshit” because of the veils cast over her, a Lucy who might find herself having to wear a Guerrilla Girls mask, or nothing at all.