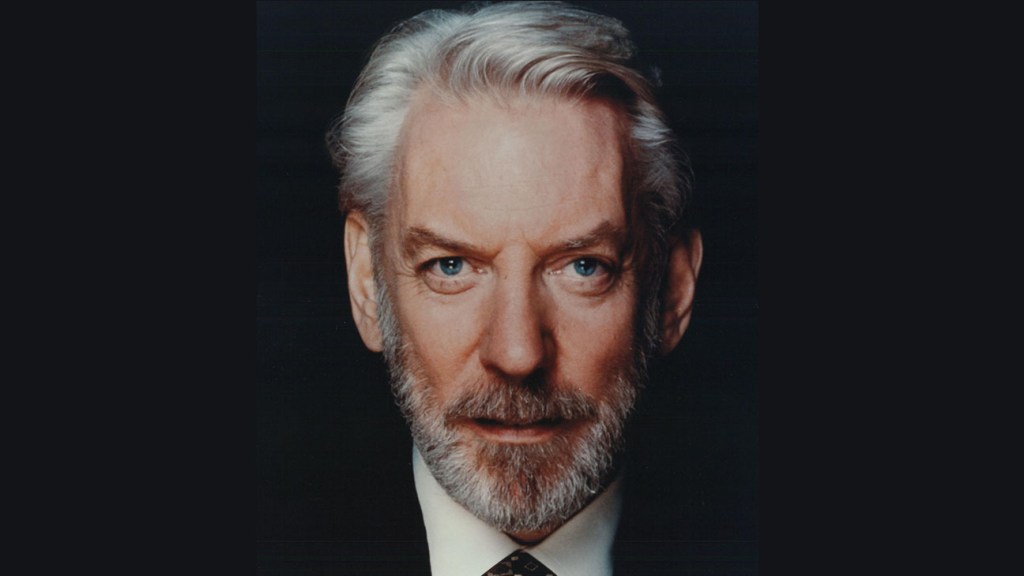

Donald Sutherland

Courtesy of HBO

If being a Hollywood star is about having either major box office clout or a few Oscar nominations (and, preferably, at least one win), the great Donald Sutherland never had any of those nominations. So why, since his death last Thursday at the age of 88, has he been celebrated around the world as one of the true legends of modern cinema?

The reason is simple: Canadian-born Sutherland, whose incredibly prolific and versatile career began in 1964 with the Italian horror film, The Castle of the Living Deadpossessed the extremely rare quality – let’s call it a kind of alchemy – where he could disappear into a role while remaining Donald Sutherland at the same time.

If he was playing a sinister Nazi spy (The eye of a needle), a watered GI doctor (MASH POTATOES), an existentially loving detective (Clute), the benevolent English patriarch of a classic 19th-century novel (Pride and Prejudice) or the evil, charismatic leader of a violent adolescent dystopia (The hunger Games series), the actor has always been, inevitably, himself.

Watching Sutherland in a movie is like watching someone in a red raincoat trying their best to blend in with a crowd of people all dressed in black: no matter how much it rains outside, that person always manages to stand out.

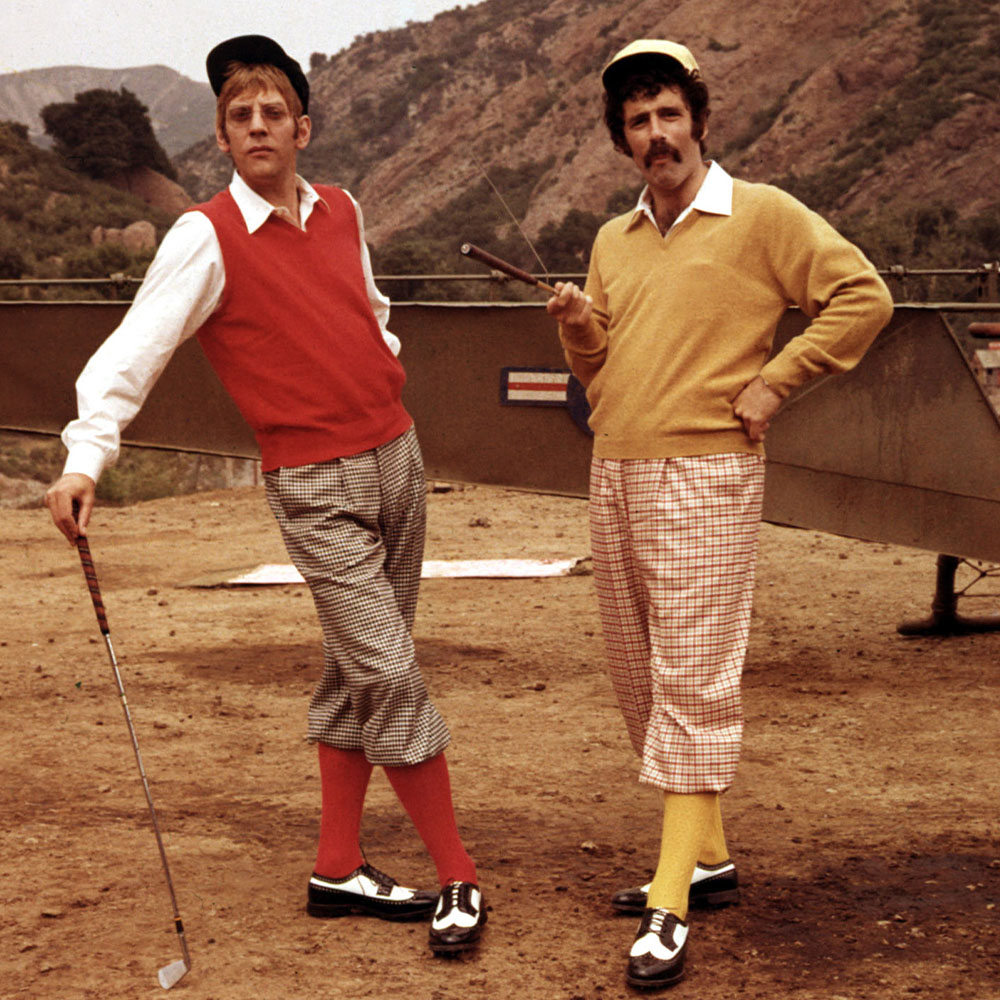

Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould in “M*A*S*H”.

Courtesy Everett Collection

This red raincoat, of course, is a reference to Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 gothic horror classic, Don’t look now, in which Sutherland hauntingly depicts a father pursued by the ghost of his deceased daughter. In this film, the actor became a man filled with overwhelming grief, or caught in the throes of ecstasy during a legendary sex scene with co-star Julie Christie, or artfully trying to restore the mosaics of ‘an Italian church. But he was still very Sutherland, with his intense eyebrows and broad grin, standing 6’4″ tall and a head taller than everyone else as he wandered around Venice in terror and desire.

Or take Sutherland’s cameo in Oliver Stone JFK, where he meets Kevin Costner’s Jim Garrison for about five minutes near the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool and ends up stealing the entire movie. He does this not just because his character, known only as Mr. humor and insight is there. in his speech, in his wolfish smile and again, in his arched eyebrows.

Those eyebrows might have kept him from becoming a matinee idol—during an audition early in his career, a producer told Sutherland that he didn’t look like “a guy next door character”—and yet he transformed them. in his punch. If there’s one expression we remember him for, it’s that playful, world-weary look he gives us, eyebrows raised, a smile forming on his face – the look of someone who has seen it all but can still be mystified and amused by all that life has to offer. tells him.

Donald Sutherland in Kelly’s Heroes.

Courtesy Everett Collection

Sutherland rose to fame in a trio of films about the Vietnam War (The dirty dozen, MASH POTATOES, Kelly’s heroes) made in the late 1960s, where his penchant for hip, countercultural comedy immediately made him stand out. But he really came into his own during the 1970s, playing characters full of guilt, sorrow, fear and trembling in classics like Clute, Don’t look nowthat of Philip Kaufman Invasion of the body snatchers remake and that of Robert Redford Ordinary people. (We should also add John Schlesinger’s oft-forgotten and very dark satire from the silent film era, The day of the grasshopperto this list.)

In these films, Sutherland played vulnerable heroes like Dustin Hoffman – men doubting their ability to stay alive or save the day, which they often did not do. And yet the actor’s spectrum was so broad that he also starred in two dense and ambitious 1970s epics by great Italian authors: Fellini’s. Casanova and that of Bertolucci 1900 – while being part of numerous comedies, Little Murders has The Kentucky Fried movie.

As far back as I can remember, the first time I saw Sutherland on screen was in National Lampoon’s Animal House – which is surely not the film for which he will be most remembered, although I clearly remember him in this film. Among all the drunk frat boys, he stood out as a weirdo professor with a hilarious and calm demeanor.

Donald Sutherland and Jane Fonda in “Klute”.

Courtesy of the Everett Collection

With around 200 credits under his belt, on the big and small screen, Sutherland loved acting so much that he was probably less selective than some of his peers. Starting in the 1980s, he had roles in everything from Sylvester Stallone’s film Lock up at Jason Statham The mecanic to something called Baltic Storm. His vast filmography, which covers all genres, reads as a reflection of the evolution of Hollywood from the early 1970s to today: from original works by directors like MASH POTATOES And Clute to IP-backed action franchises like the hugely successful hunger games series.

Sutherland memorably played the fascist President Coriolanus Snow in these films, apparently pursuing the role so that he could play a dictator who would serve as a warning to younger generations during a time when fascism was on the rise, particularly in the United States. continued the political activity of his early days, when he appeared alongside his then-girlfriend Jane Fonda in the anti-war docudrama, ALE

But in THE hunger games films, the actor also brought a melancholic depth and, as always, a shrugging villainy, to a character who might otherwise have been forgettable, standing out despite the nonstop CGI and garish production design.

Like almost everything Sutherland has done on screen in more than half a century, he brilliantly transformed himself into another person – in this case, his political opposite – while reprising a role he had perfected throughout his long and distinguished career: himself.