Researchers at the University of Cambridge have discovered that regulatory T cells form a unique, mobile population that patrols throughout the body to repair tissue damage. This new understanding could revolutionize the treatment of various diseases by enabling targeted immune suppression and tissue regeneration in specific organs, potentially improving the effectiveness and speed of treatments. The team is currently working on clinical trials to further explore these findings.

Cambridge researchers have discovered that regulatory T cells travel throughout the body to repair tissues, paving the way for targeted treatments for various diseases.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have discovered that regulatory T cells, a type of white blood cell, form a large, unique group that constantly circulates throughout the body to seek out and repair damaged tissue.

This overturns traditional thinking that regulatory T cells exist as multiple specialized populations restricted to specific parts of the body. This discovery has implications for the treatment of many different diseases, because almost all illnesses and injuries trigger the body’s immune system.

Current anti-inflammatory medications treat the entire body, rather than just the part being treated. The researchers say their findings mean it might be possible to shut down the body’s immune response and repair damage in any specific part of the body, without affecting the rest. This means higher, more targeted doses of drugs could be used to treat the disease – with potentially rapid results.

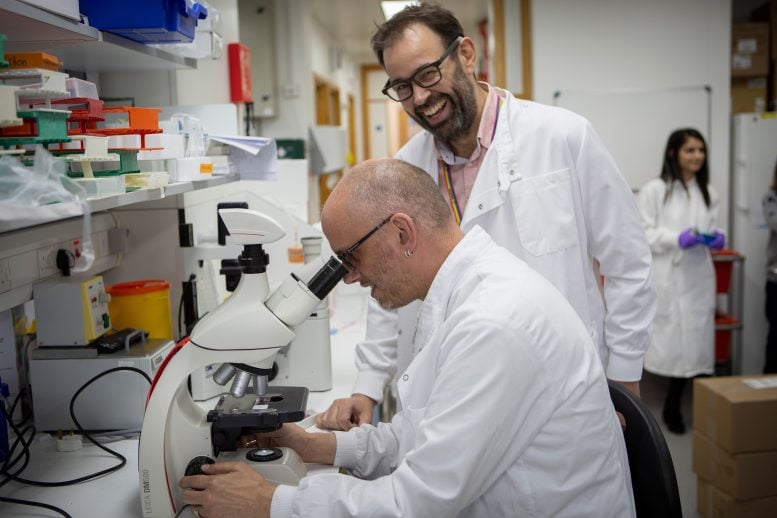

Professor Adrian Liston and Dr James Dooley, lead authors of the study, use microscopy to track anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells as they circulate through tissues. Credit: Louisa Wood/Babraham Institute

Unified Healing Force

“We have discovered new rules of the immune system. This “unified army of healers” can do it all: repair injured muscles, make your fat cells respond better.

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>insulinand regrow hair follicles. To think that we could use it in such a large number of diseases is fantastic: it has the potential to be used for almost everything,” said Professor Adrian Liston of the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge, lead author of the article.

To arrive at this discovery, the researchers analyzed the regulatory T cells present in 48 different tissues of the mouse body. This revealed that cells are neither specialized nor static, but move throughout the body to where they are needed. The results are published today in the journal Immunity.

Regulatory T cells can migrate from one tissue to another via the blood. The cells take only a few minutes to move through the body, then slow to a crawl once they enter a tissue, spending an average of three weeks inside the tissue before exiting. Credit: Equinox Graphics

“It’s hard to think of any disease, injury or infection that doesn’t involve some sort of immune response, and our findings really change how we might control that response,” Liston said.

He added: “Now that we know that these regulatory T cells are present throughout the body, we can in principle begin to develop immune suppression and tissue regeneration treatments targeting a single organ – a significant improvement over current treatments. which resemble typing treatments. the body with a hammer.

Drug development and clinical applications

Using a drug they have already designed, the researchers have shown – in mice – that it is possible to attract regulatory T lymphocytes to a specific part of the body, increase their number and activate them to deactivate the immune response and promote healing in just seconds. an organ or tissue.

“By increasing the number of regulatory T cells in targeted areas of the body, we can help the body better repair itself or manage immune responses,” Liston said.

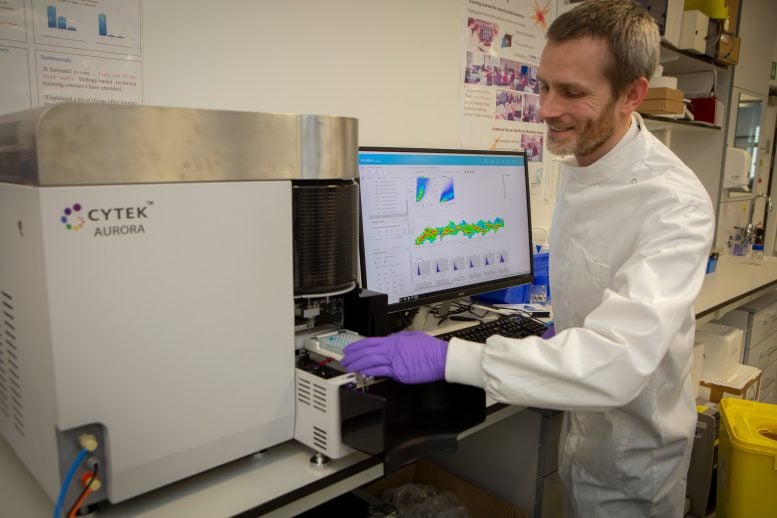

Dr. Oliver Burton, lead author of the study, uses spectral cytometry to analyze anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells from different tissues. Credit: Louisa Wood, Babraham Institute

He added: “There are so many different diseases where we would like to stop an immune response and start a repair response, for example autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, and even many infectious diseases. »

Most symptoms of infections like COVID do not come from

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”({“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”})” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>virus itself, but from the body’s immune system which attacks the virus. Once the virus is past its peak, regulatory T cells should turn off the body’s immune response, but in some people the process is not very effective and can lead to ongoing problems. This new discovery means it might be possible to use a drug to stop the immune response in the patient’s lungs, while allowing the immune system in the rest of the body to continue functioning normally.

In another example, people who receive an organ transplant must take immunosuppressive medications for the rest of their lives to prevent organ rejection, because the body mounts a severe immune response against the transplanted organ. But this makes them very vulnerable to infections. This new discovery helps design new drugs to stop the body’s immune response only against the transplanted organ, while maintaining normal functioning of the rest of the body, thereby allowing the patient to lead a normal life.

Most white blood cells attack infections in the body by triggering an immune response. In contrast, regulatory T cells act as a “unified army of healers” whose goal is to shut down this immune response once it has done its job – and repair the tissue damage it causes.

The researchers are currently raising funds to create a spin-off company, with the aim of conducting clinical trials to test their results in humans over the next few years.

Reference: “The tissue-resident pool of regulatory T cells is shaped by transient multi-tissue migration and a conserved residency program” by Oliver T. Burton, Orian Bricard, Samar Tareen, Vaclav Gergelits, Simon Andrews, Laura Biggins, Carlos P. Roca, Carly Whyte, Steffie Junius, Aleksandra Brajic, Emanuela Pasciuto, Magda Ali, Pierre Lemaitre, Susan M. Schlenner, Harumichi Ishigame, Brian D. Brown, James Dooley and Adrian Liston, June 18, 2024, Immunity.

DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.05.023

The study was funded by the European Research Council and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.