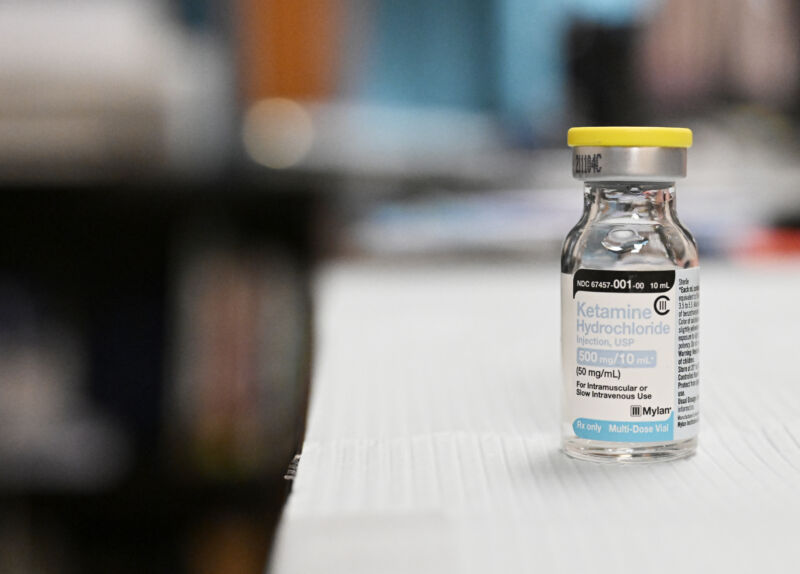

After an MDMA-based therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder failed to impress Food and Drug Administration advisers earlier this month, researchers are moving forward with another psychedelic – an oral release dose slow of the hallucinogenic drug ketamine – as therapy for treatment-resistant depression.

In a mid-stage randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial, researchers tested slow-release ketamine tablets, taken twice a week. The trial, sponsored by New Zealand-based Douglas Pharmaceuticals, showed ketamine was safe compared to placebo. At the highest dose in the trial, the treatment showed some effectiveness against depression in patients who had previously tried an average of nearly five antidepressants without success, according to results published Monday in Nature Medicine.

But the phase II trial, which began with 231 participants, indicated that the group of patients likely to benefit from the treatment could be quite limited. The researchers behind the trial chose an unusual “enrichment” design to test the depression treatment. The goal was to counteract the high failure rates typically seen in trials of depression treatments, even in patients without cases of treatment resistance. But even after selecting patients who initially responded to ketamine, 59.5 percent of spiked participants still dropped out of the trial before it was completed, largely due to a lack of effectiveness.

Enriched design

During the initial enrichment phase of the trial, all 231 participants received a 120-milligram ketamine pill daily for five days. All participants knew they were taking ketamine, which could introduce bias if they expected the drug to work. A few days after their five-day treatment, on day eight, the researchers rated their depression symptoms using a common standardized scale called the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). It is a 10-question questionnaire, in which each item is rated from 0 to 6 points for a maximum score of 60. The higher the score, the more severe the depression. The 231 participants began the trial with scores of 20 or higher, indicating at least moderate depression. The average score was about 30. Researchers considered a patient to have achieved remission of their depressive symptoms if their score fell to 10 or less during the trial.

By day eight of the enrichment phase, 132 of 231 participants (57 percent) achieved remission, and an additional 36 participants achieved at least a 50 percent reduction in their MADRS score. Thus, 168 (72%) of the initial trial participants progressed to the next phase of the trial. Those who did not respond to the medication did not continue.

The next phase was the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled part of the trial, which also tested different dosage levels of ketamine. The 168 ketamine-sensitive patients were randomly assigned to one of five groups: a placebo group or a ketamine group, with doses of 30 mg, 60 mg, 120 mg, or 180 mg. Group sizes ranged from 31 to 37 participants. Each group received their dose twice a week for 12 weeks.

At the end, on day 92 of the trial, the researchers were able to see a dosage response, that is, there appeared to be a gradual improvement in depressive symptoms between the groups as the dose increased until ‘at the highest level, 180 mg. However, only this 180 mg dose showed statistically significant improvements. At day 92, the remaining participants in the 180 mg group had MADRS scores that were, on average, 6.1 points lower than the scores of the remaining participants in the placebo group. In other words, participants in the 180 mg group had final scores that represented an average drop of 14 points from their initial MADRS score, while the placebo group had, on average, a drop of 8 points.

The researchers reported that these results showed “statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in depressive symptoms.”

The dropouts

However, it is important to note that on day 92 of the trial, only 68 of the 168 ketamine-sensitive participants remained in the trial. The other 100 participants (59.5 percent of 168) then dropped out. Of the 100 people who dropped out of the study, 94 did so due to lack of effectiveness (defined as a MADRS score of 22 or higher during the trial). For the remaining six, four dropped out for unspecified reasons, one dropped out due to an adverse event, and one 65-year-old man receiving the 180 mg dose committed suicide on day 42 of the trial. The researchers who conducted the trial determined that this was due to depression.

On day 92, only 11 of 37 participants remained in the placebo group and 18 of 32 remained in the 180 mg dose group. Thus, the final statistically significant difference of 6.1 points calculated between the placebo group and the group receiving the 180 mg dose was based on the scores of only 29 of the 168 participants.

The authors acknowledge that their trial design “is likely to overestimate treatment response levels in the population” and that “future unenriched clinical trials are needed to address this issue.”

Meanwhile, researchers reported that oral doses of ketamine appeared safe. During the trial, no cardiovascular side effects were observed, in particular no increase in blood pressure as previously observed with ketamine. There were also low rates of dissociation as well as very low rates of sedation, the researchers wrote. Otherwise, common side effects included mild to moderate headache, dizziness, anxiety, depressed mood, and dissociation.

The study did not collect specific data on potential abuse or diversion. Most doses administered during the second phase of the trial took place at home, which may raise concerns among clinicians. The researchers only reported anecdotally that they were not aware of any participants craving the pills. They also noted that ketamine tablets are difficult to open. One participant was excluded from the trial due to “lack of compliance.”