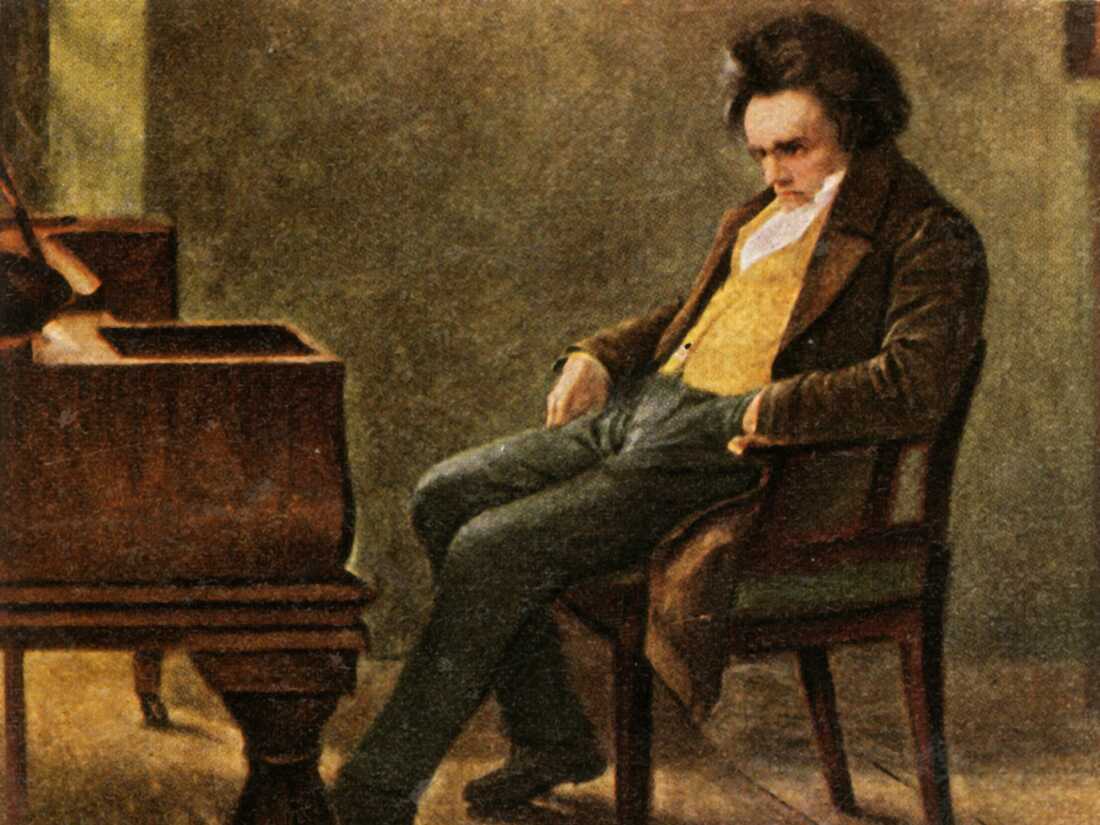

“Beethoven” (1936). A new study suggests the German composer and pianist may have suffered from lead poisoning.

The Print Collector/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

The Print Collector/Getty Images

Ludwig van Beethoven was a prodigious composer. He is credited with 722 individual works, including symphonies, sonatas and choral music, creations that pushed the boundaries of composition and performance and helped pave the way for the Romantic era of music. But aside from the pianoforte, Beethoven’s life was marked by deafness, debilitating gastrointestinal disorders and jaundice.

A little over a year ago, scientists announced that they had sequenced Beethoven’s genome from preserved strands of hair. They found genetic risk factors for liver disease, but nothing else very conclusive.

But some researchers have long wondered whether some of the answers lie beyond his genes — particularly whether heavy metal toxicity might have something to do with his many illnesses.

After testing a few more strands of the composer’s hair, a team of scientists suggests in the journal Clinical Chemistry that Beethoven was almost certainly exposed to lead – and that this could have contributed to the health problems that so characterized the famous composer’s life.

The struggles of Ludwig van Beethoven

Lead is a toxic metal naturally present in the earth’s crust. However, “its widespread use has resulted in significant environmental contamination, human exposure, and significant public health problems in many parts of the world,” according to the World Health Organization.

“Lead has no use in the body,” says Howard Hu, a medical epidemiologist at the University of Southern California. “But unfortunately it also mimics some of the other more essential elements. He’s an imposter. It incorporates itself into various enzymatic and molecular structures in the body and then screws them up.

And it can lead to all kinds of problems, from brain damage to hypertension to kidney problems.

Beethoven began losing his hearing in his late 20s and was completely deaf by his mid-40s. Additionally, he suffered from jaundice and debilitating gastrointestinal problems. At one point he wrote a letter to his brothers, now called the Heiligenstadt Testament, requesting that his health problems be described after his death.

“He wanted the world to know the truth about the cause of his illnesses,” says Paul Jannetto, director of the Mayo Clinic Metals Laboratory.

The metals lab typically tests blood and urine samples for exposure to heavy metals, such as lead, mercury, and arsenic. “Clinically, our menu of tests is basically the periodic table,” says Jannetto. One of the lab’s typical responsibilities is testing children for lead to try to determine whether a patient’s symptoms could be due to heavy metal toxicity.

So Jannetto vividly remembers the moment when a colleague sent him a very different request: Would he be willing to test Beethoven’s hair for the presence of heavy metals?

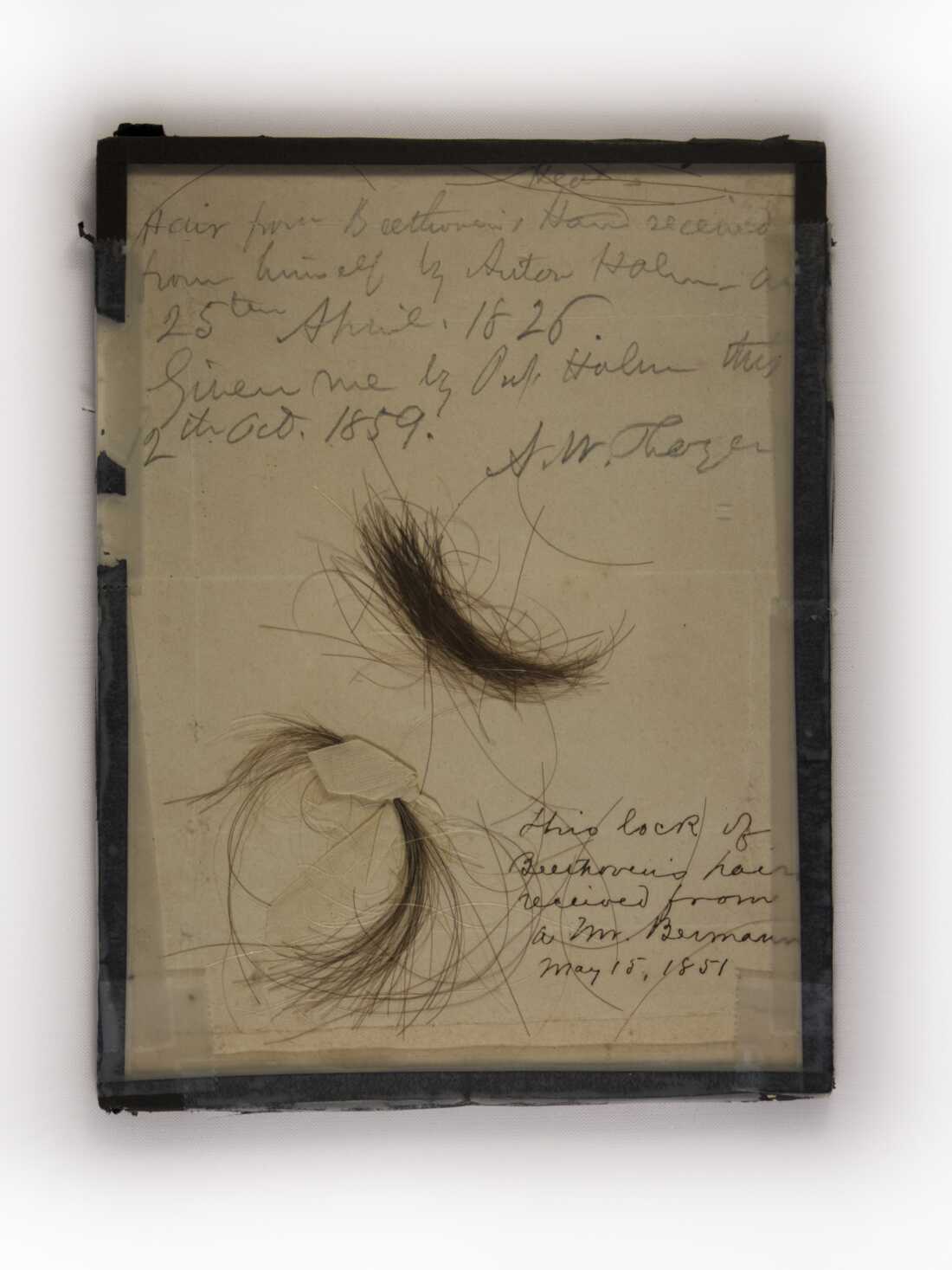

These two locks of Beethoven’s hair were tested for lead in 2023.

Kevin Brun

hide caption

toggle caption

Kevin Brun

When a person is exposed to lead, some of the harmful metal is deposited in their hair. This means that even without a blood sample, scientists can use a person’s hair to determine their lead levels posthumously.

So the owner of two separate strands of Beethoven’s hair placed two or three dozen strands in a special collection kit and shipped it to the Mayo Clinic, where Metals Lab technical coordinator Sarah Erdahl received it. .

“I used tweezers,” says Erdahl, who said he felt no temptation to touch the composer’s hair with his bare hands. “My heart was pounding and I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is so important.’ When you have a small amount of hair, every strand counts.

Jannetto agreed, adding that this approach also extends to the lab’s usual live patients.

“Behind every sample, whether it’s blood (or hair), there is a person,” he says. “And that’s why it’s valuable and we treat it with care.”

Erdahl carefully rinsed and treated the hair before running it through the instrument that measures heavy metals. The levels of arsenic and mercury in Beethoven’s hair were slightly elevated.

Lead levels, on the other hand, were 64 to 95 times higher than those in a person’s hair today.

It was a dramatic revelation – one that might explain why, at that moment, the opening bars of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony crashed into Erdahl’s brain:

“Dun dun dun dun.”

“That’s way higher than any of the other patient samples we see,” she remembers thinking. “It’s extremely significant.”

When classical music meets heavy metal

This substantial accumulation of toxic metal likely came from the goblets and glasses from which Beethoven drank, from certain medical treatments of that era, and from his wine consumption.

“We know that Beethoven loved his wine,” says Jannetto. “And back then, it was not uncommon to add lead acetate to the cheaper wines, because it binds the acids to add a smoother flavor to the wine.”

Jannetto says that even for people of his era, lead levels in Beethoven’s hair would have been about 10 times higher than average. “It showed that he was chronically exposed to high concentrations of lead,” he says.

The lead wouldn’t have killed him, but it likely contributed to his health problems.

“Many of the illnesses that Beethoven suffered from are classic signs and symptoms that a neurologist or clinician would see in a patient exposed to lead,” Jannetto says. These include liver disease (reportedly made worse by his genetic risk factor, regular alcohol consumption, and hepatitis B infection), gastrointestinal problems, and hearing loss. .

Hu, who was not involved in the research, praised the work.

“It’s good science,” he said. “I think it was pretty damn rigorous.”

Hu has been studying lead exposure and toxicity for nearly 40 years, particularly in the context of some low- and middle-income countries where lead contamination can still be a problem.

“It’s still a major problem globally,” he says, “because of lead contamination in spices, cooking utensils and all kinds of other sources around the world.”

Still, Hu can’t help but reflect on how Beethoven handled his virtuoso composition despite playing the lead role.

“It makes you even more impressed with what he was able to accomplish,” Hu says.

He wonders whether the health problem itself contributed to shaping the emotional contours of some of Beethoven’s compositions.

“I don’t know,” Hu laughed. “It’s fun to speculate about that.”