Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with information about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more..

CNN

—

A fossilized ear bone discovered in a cave in Spain revealed the presence of a Neanderthal child who lived with Down syndrome until the age of 6, according to a new study.

The discovery suggests that community members cared for this vulnerable child, who lived at least 146,000 years ago. The research is at odds with the image of Neanderthals, ancient human relatives who died out around 40,000 years ago, as brutal cavemen.

“The individual would have required continuous and intensive care,” said paleoanthropologist Mercedes Conde-Valverde, lead author of a study on the bone published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The child “suffered severe hearing loss and had severe balance problems and episodes of vertigo,” said Conde-Valverde, an assistant professor of physical anthropology at the University of Alcalá in Spain.

Muscle weakness would also have made breastfeeding and movement difficult, she added.

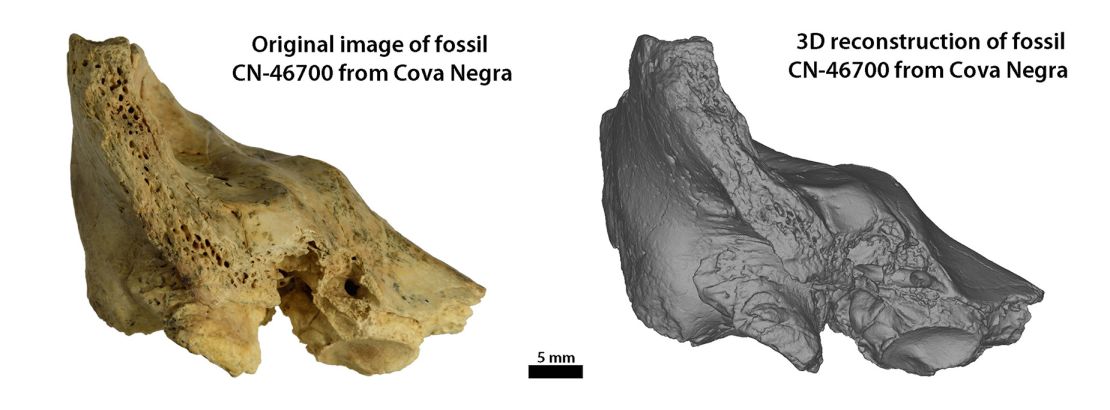

This tiny fossil was discovered in 1989 at the archaeological site of Cova Negra, in the province of Valencia, Spain. Archaeologists only recently discovered the specimen, however, after combing through fragments of fauna collected from the site during a study of the material.

“We were able to identify him as a Neanderthal because of the particular proportions of his semicircular canals, characteristic of Neanderthals,” Condé-Valverde said, referring to the internal tubes of the ear.

The study did not include precise dating of the bone, which would require extracting ancient DNA, but Neanderthals occupied the site 146,000 to 273,000 years ago. The research team has not determined the sex of the young Neanderthal.

People with Down syndrome can live a long time today, but it is surprising that the child lived beyond 6 years old, Conde-Valverde said.

Life in the Stone Age would have been demanding. The study noted that Neanderthals were highly mobile, moving regularly from place to place. The care required for the child’s survival over a prolonged period probably meant that the mother depended on the cooperation and support of other members of the group.

Even in the recent past, it was common for people with Down syndrome to die during childhood. According to the study, the life expectancy in 1929 for children with Down syndrome, a condition caused by a partial or complete extra chromosome, was 9 years. By the 1940s, the expected lifespan had increased to 12 years.

Today, about 1 in 772 babies in the United States are born with Down syndrome, and life expectancy now exceeds 60 years, according to the National Down Syndrome Society of the United States.

The oldest known case of Down syndrome in Homo sapiens, our own species, dates back to at least 5,300 years. Using ancient DNA, the authors of a study published in February identified six cases in prehistoric populations. None of the children lived more than 16 months.

Down syndrome has also been documented in chimpanzees. A January 2016 study highlighted the case of a chimpanzee with Down syndrome who survived up to 23 months thanks to the care received by the mother, with the help of the eldest daughter.

However, when the daughter stopped caring for her own offspring, the mother was unable to provide the necessary care and the offspring died, according to the study.

Conde-Valverde and his colleagues believe the bone belonged to a child with Down syndrome due to a series of abnormalities in the structure of the inner ear.

These include an abnormal shape of the lateral semicircular canal (the shortest ear canal), an enlarged vestibular aqueduct, a narrow bony canal that runs from the inner ear to the interior of the skull and a reduction in the overall size of the bony chamber of the cochlea.

“Some of these pathologies commonly appear in various syndromes, but the combination present in the Cova Negra fossil has only been described in contemporary people with Down syndrome,” she said.

Definitive proof that the child had Down syndrome would require recovery of ancient DNA from the fossil, but that had not yet been possible, she said.

Previous studies of archaeological finds have suggested that Neanderthals cared for vulnerable members of their group.

A Neanderthal buried in Shanidar Cave in what is now Iraq was deaf and suffered a paralyzed arm and head trauma that likely left him partially blind, but he lived a long life, study finds from October 2017.

A Neanderthal skeleton known as the “Old Man of La Chapelle” discovered in present-day central France suffered from degenerative arthritis and may have been fed by other members of his group, according to a February 2019 study.

Condé-Valverde said the discovery of the Cova Negra fossil supported the existence of true altruism among Neanderthals.

“For decades, it has been known that Neanderthals cared for their vulnerable companions,” Condé-Valverde said.

“However, all known cases of caregiving involved adult individuals, leading some scientists to believe that this behavior was not true altruism but simply an exchange of assistance between equals,” she said.

“What was not known until now was the case of a person who received extra-maternal care from birth, although it could not reciprocate.”

Today, most parents don’t view childcare as an “expectation of reciprocity,” and that’s unlikely to have been the case among Neanderthals, said Penny Spikins, a professor of archaeology at the University of York in the United Kingdom and author of “Hidden Depths: The Origins of Human Connection.”

Humans likely evolved an instinctive and emotional response to care for infants to ensure their survival, said Spikins, who was not involved in the research.

“This discovery shows how similar we Neanderthals were in many ways, particularly in our common human desire to care for the most vulnerable,” she said.

“We can imagine that this child was loved and cared for like the others. »