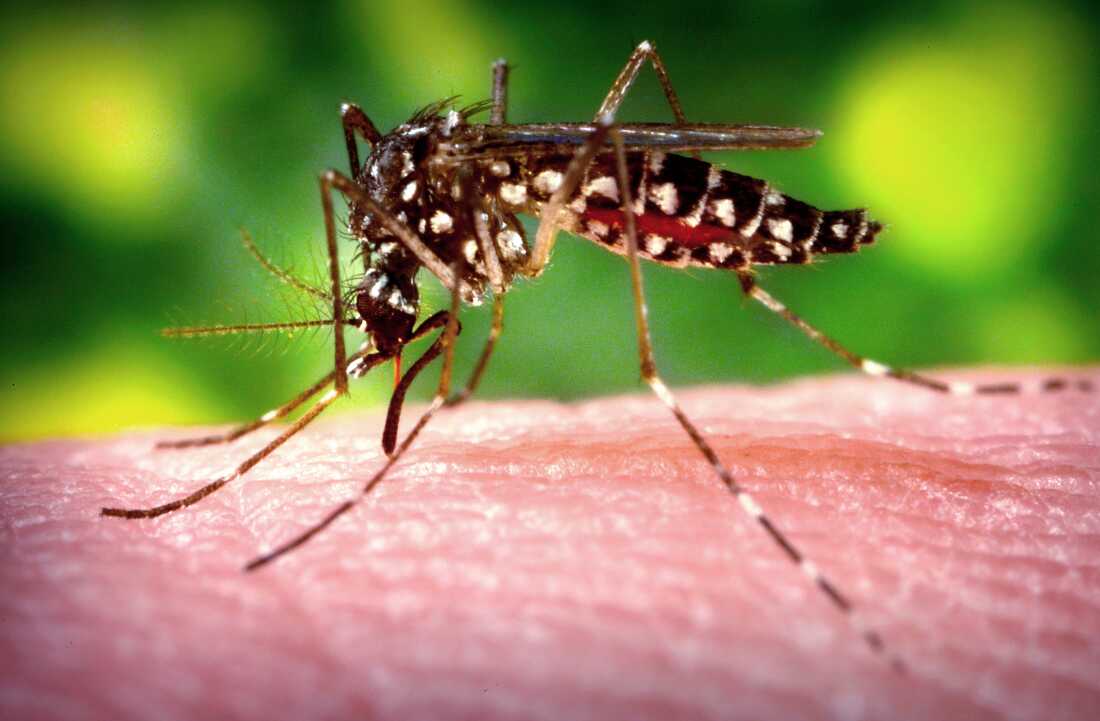

A female Aedes aegypti The mosquito, the species that transmits dengue fever, feeds on the blood of a human host.

James Gathany/CDC

hide caption

toggle caption

James Gathany/CDC

It’s already a record year for dengue infections in Central and South America, with nearly 10 million cases diagnosed so far.

Now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is warning of an increased risk of virus transmission from mosquitoes in the United States as summer temperatures and holiday travel heat up.

This week, the CDC asked health care providers to be vigilant and test for cases, especially among people with fever who recently returned from places where dengue fever is prevalent.

“Currently, there is no evidence of an outbreak in the continental United States,” said Gabriela Paz-Bailey, chief of the CDC’s Dengue Branch, based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. “But around the world, dengue cases have been increasing at an alarming rate.” “During the summer months, we expect people to travel more to areas where dengue is common, which could lead to greater local transmission in the United States. »

The United States has recorded around 2,200 cases this year. And about 1,500 of those cases were acquired locally, primarily in Puerto Rico, where the dengue virus is considered endemic, meaning in constant and continuous circulation.

Puerto Rico declared a public health emergency over dengue fever in March after cases rose rapidly at an unusually early time. Locally acquired cases have also been reported this year in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Florida, Paz-Bailey said.

To be clear, the CDC does not expect to see large outbreaks in the United States this summer. Instead, the agency expects more travel-related cases and small chains of local transmission linked to those cases, Paz-Bailey says. These chains can appear in any state with an established population of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the species most associated with their transmission in the Americas.

In recent years, local cases of dengue have been observed in Arizona, California and Texas. “With the rising temperatures, we need to continue to prepare and strengthen the surveillance system so that we can monitor the emergence of dengue in new areas,” Paz-Bailey said.

Why is the dengue virus exploding now?

A few intersecting factors related to weather, waning immunity and human behavior are contributing to “the explosive epidemic that has evolved over the last year,” says Dr. Albert Ko, a professor of public health at Yale University who has worked with dengue patients in Brazil for 30 years.

First, it’s been a hot and humid year in South America, creating ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes. Populations of potential dengue vectors are booming. This year, mosquitoes have brought the disease to areas of southern Brazil and Argentina where it had never been detected before, “a testament to climate change,” which is expanding the insects’ range, Ko says.

Second, dengue outbreaks tend to be cyclical. Large outbreaks occur every few years, with the last one occurring in 2019. The cyclical pattern of dengue outbreaks is related to how population-level immunity rises and falls, Ko says.

There are four distinct strains of dengue, and a person who recovers from one type is protected against all of them for a few years. But that immunity wanes over time, “and then you become susceptible to the other three,” Ko says. At the population level, immunity is high after a major outbreak, then wanes in the years that follow, setting the stage for a new wave of dengue infections.

And third, the dengue virus preys on human travelers, who will see family, friends and places they missed when travel was halted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Human mobility, whether short or long distance, plays a significant role in moving the virus,” says Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, an environmental scientist and global health researcher at Emory University. “Humans are the vector, the ones who move the virus. They carry the virus even further than mosquitoes. They get bitten by mosquitoes that have dengue and, often inadvertently, bring it to where they go next.”

About 75% of people infected with dengue have mild or no symptoms. “So this could result in a person traveling to an area where there is active transmission of dengue, contracting dengue, returning home and then transmitting dengue to a mosquito,” all without knowing that “she carries the dengue virus,” explains Paz-Bailey. This mosquito could bite other people, potentially triggering a local chain of transmission.

If most people are asymptomatic, how serious can dengue be?

In a quarter of cases, people infected with dengue feel very unwell. “About three to four days after being bitten, the virus spreads in the body, causing systemic illness,” says Ko, who has treated thousands of dengue patients. “Symptoms (include) fever, very severe body aches, joint pain and very, very severe headache.”

A few patients will develop severe dengue, which can include a condition called capillary leak syndrome. “It causes our blood vessels to leak, and people become dehydrated and go into shock … they need urgent medical care, like resuscitation with intravenous fluids, to save their lives,” says Yale’s Ko. People with fever and headaches due to dengue should stick to Tylenol or acetaminophen, he says, and avoid aspirin, because aspirin thins the blood and can exacerbate the bleeding effects of the disease.

Dengue fever can be serious and deadly whether a person contracts it for the first, second, third or fourth time. But there’s a particularly pronounced risk of severe illness the second time around, says the CDC’s Paz-Bailey. This is due to a phenomenon associated with dengue known as antibody-dependent enhancement, in which a first infection with dengue can prime a person’s immune system to help the virus more easily infect cells when ‘a second infection.

The groups most at risk of serious illness are infants, pregnant women and the elderly.

What precautions can be taken?

People can protect themselves from mosquito bites by wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants and using EPA-registered insect repellents, says the CDC’s Paz-Bailey.

They can also help reduce the buzz of mosquitoes in and around their homes by “draining standing water, using mosquito nets and, if possible, using air conditioning, as this helps keep mosquitoes out,” she says.

People with fever, severe headache, or other symptoms consistent with dengue fever should seek medical attention, and health care providers should be prepared to assess their symptoms and travel history and, if necessary, test their blood for dengue fever.

Dengue is a nationally notifiable disease; any cases detected must therefore be reported to local health authorities. This will help determine where the virus is spreading and could boost local education and mosquito control efforts, Ko says.

A dengue vaccine has been stopped

A dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia, is approved for use in the United States where the virus is endemic, such as Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. However, the three-dose vaccine, which requires multiple blood tests and repeated visits to the doctor’s office, has been difficult to administer and slow to uptake. Sanofi-Pasteur has stopped making the vaccine, citing a lack of demand, and the last remaining doses will expire in 2026, Paz-Bailey said.

According to Yale’s Ko, the hope for the future is twofold: better mosquito control measures that reduce dengue transmission and better vaccines that protect the unexposed population.

“The downside of decreasing transmission is that people become vulnerable because they haven’t been infected,” he explains. “But if we have both a vaccine and (better) vector control methods, we mitigate that risk.” »

Ko sees progress on both fronts — citing developments involving bacteria that can interfere with mosquito breeding and another dengue vaccine that has been approved in some countries but not in the United States.

With better interventions that tackle mosquito-borne diseases from different angles, Ko says, the country’s response to diseases like dengue could become “substantially effective” and many more people could be saved.