Getty Images

Until now, even AI companies have struggled to find tools that can reliably detect when a text was generated using a large language model. Now, a group of researchers has developed a new method to estimate LLM usage in a large set of scientific literature by measuring which “excess words” began appearing much more frequently during the LLM era (i.e., in 2023 and 2024). The results “suggest that at least 10% of abstracts in 2024 were treated with LLMs,” the researchers said. In a preliminary paper published earlier this month, four researchers from Germany’s University of Tübingen and Northwestern University said they drew inspiration from studies that measured the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by looking at excess deaths compared to the recent past. Looking similarly at “excessive word usage” after LLM writing tools became widely available in late 2022, the researchers found that “the advent of LLMs led to a sharp increase in the frequency of certain style words” that was “unprecedented in both quality and quantity.”

Dive into

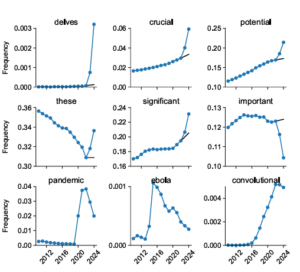

To measure these vocabulary changes, the researchers analyzed 14 million abstracts of articles published on PubMed between 2010 and 2024, tracking the relative frequency of each word as it appeared each year. They then compared the expected frequency of these words (based on the pre-2023 trend line) to the actual frequency of these words in abstracts from 2023 and 2024, when LLMs were in widespread use.

The results revealed a number of extremely rare words in these pre-2023 scientific abstracts that suddenly gained popularity after the introduction of LLMs. The word “excavation,” for example, appears in 25 times more articles in 2024 than would be expected from the pre-LLM trend; words like “presentation” and “underscore” also increased ninefold. Other previously common words became significantly more common in post-LLM abstracts: the frequency of “potential” increased by 4.1 percentage points; “findings” by 2.7 percentage points; and “crucial” by 2.6 percentage points, for example.

Of course, these types of changes in word usage could occur independently of LLM usage: the natural evolution of language means that words sometimes come in and out of fashion. However, the researchers found that in the pre-LLM era, such massive and sudden year-on-year increases were only observed for words related to major global health events: “ebola” in 2015; “zika” in 2017; and words like “coronavirus,” “lockdown,” and “pandemic” for the period 2020 to 2022.

However, after the LLM, researchers found hundreds of words whose scientific usage increased suddenly and sharply, but which had no connection to world events. In fact, while the words in excess during the COVID pandemic were overwhelmingly nouns, researchers found that the words that increased in frequency after the LLM were overwhelmingly “words of style” like verbs, adjectives and adverbs (a small sample: “across, additional, comprehensive, crucial, enhancement, exposed, insights, especially, especially, within”).

This is not a completely new finding – the increased prevalence of “delve” in scientific articles has, for example, been widely noted in recent times. But previous studies typically relied on comparisons with “verifiable” human writing samples or lists of predefined LLM markers obtained outside the study. Here, the pre-2023 set of summaries acts as its own effective control group to show how vocabulary choice has changed overall in the post-LLM era.

A complex interaction

By highlighting hundreds of “marker words” that have become much more common in the post-LLM era, the telltale signs of LLM usage can sometimes be easy to spot. Consider this example of an abstract line that researchers have discussed, with the marker words highlighted: “A complete understanding of the complex interaction between (…) and (…) is pivot for effective therapeutic strategies.

After running some statistical measures of the appearance of keywords in individual articles, the researchers estimate that at least 10% of the articles published after 2022 in the PubMed corpus were written with at least some LLM assistance. That figure could be even higher, the researchers say, because their set may be missing LLM-assisted abstracts that don’t include any of the keywords they identified.

These measured percentages can also vary significantly across different subsets of items. The researchers found that articles written in countries like China, South Korea, and Taiwan showed LLM marker words in 15 percent of cases, suggesting that “LLMs could…help non-natives edit English texts, which could justify their intensive use. On the other hand, the researchers suggest that native English speakers “might (simply) be better at noticing and actively removing unnatural style words from LLM results”, thereby hiding their use of LLM from this type of analysis.

Detecting LLM usage is important, the researchers note, because “LLMs are notorious for fabricating references, providing inaccurate summaries, and making false claims that appear authoritative and convincing.” But as knowledge of the telltale LLM keywords begins to spread, human editors may become more effective at removing these words from generated text before it is shared with the world.

Who knows, maybe future big language models will perform this type of frequency analysis themselves, decreasing the weight of marker words to better mask their results as human-like. Before long, we may need to call on Blade Runners to spot the AI generative text lurking among us.