yes-hip

Written by Sam Kovacs

Introduction

Last Sunday, I published an article on Seeking Alpha titled, “If I Had to Retire With 10 Dividend Aristocrats, These Would Be The Ones.”

AI Art by the Author

Those who read the article understood the message, but Others jumped into the comments section to ask me, “Why the hell would you want to retire with just these 10 Dividend Aristocrats?”

The answer, of course, was that I wouldn’t. For one thing, I’m not entirely convinced by the assumption that a quarter-century of uninterrupted dividend growth is necessarily a positive signal.

One only has to look at 3M (MMM), Walgreens Boots Alliance (WBA) and AT&T (T) over the past few years to realize that even the safest “dividend aristocrats” can fall apart and collapse.

I believe that while dividend growth history is an important metric to consider when evaluating dividend security is only a secondary input.

The ability and willingness to increase the dividend comes much higher in the selection process.

Still, the exercise of narrowing down the Dividend Aristocrats list to a list of stocks I’d be willing to buy was a good one, because it really narrowed the list down to 10 picks.

- NextEra Energy (NEE)

- Lowes (BAS)

- McDonald’s (MCD)

- PepsiCo (PEP)

- Chevron (CVX)

- Aflac (AFL)

- AbbVie (ABBV)

- Automatic data processing (ADP)

- IBM (IBM)

- Real estate income (O)

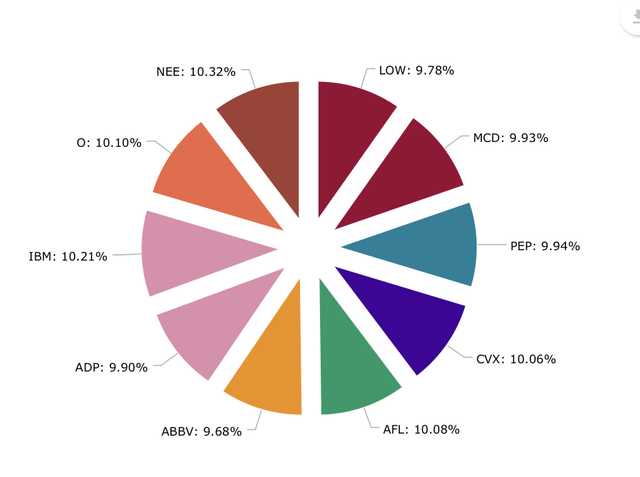

I thought it would be helpful to show you what a portfolio of these stocks would look like, so I’ve created an illustrative portfolio to walk you through the process.

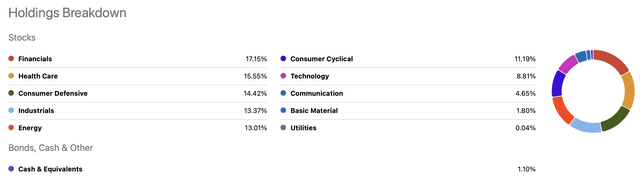

Portfolio diversification

The upside right off the bat, assuming we create a $10,000 position in each of these 10 stocks, is that you would be pretty well diversified. You would be overweight in the technology and consumer discretionary sectors, which is perhaps not the orientation I would want to have in today’s market.

Additionally, we would be missing exposure to the industrials, communications and materials sectors. There is nothing wrong with not having exposure to all sectors, but this approach would not allow us to achieve that. By definition, we were not going to be able to have exposure to all 11 sectors with only 10 stocks.

Dividend Freedom Tribe

These would also be very different from the components of Schwab’s US Dividend ETF (SCHD). The ETF does not include any utilities or REITs. I’m sure everyone would agree that with the Fed poised to cut rates, underexposure to the two most interest rate-sensitive sectors could be a mistake.

Looking for Alpha

But my problem with such a portfolio is not that I only own 10 stocks. While I prefer to own more than 10, thinking that 30 is a good minimum for investors, and I personally prefer the 40-70 range, I can admit that if chosen with extreme caution, a 10-stock portfolio could work.

No, my biggest problems come from the dividend potential of such a portfolio.

Dividend profile

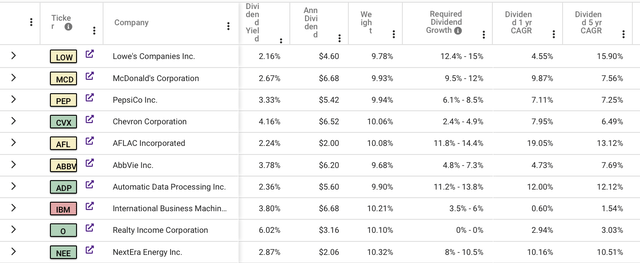

In the table below, you will see for each of these actions whether I consider it a “Buy”, a “Hold” or a “Sell” based on the color code of the labels.

This is part of the problem I would run into if someone were determined to buy 10 dividend aristocrat stocks at current prices. In most cases, they would do so by investing in stocks that are not attractively priced to buy.

Dividend Freedom Tribe

As a reminder, my framework is quite simple:

- There are prices at which a stock is undervalued relative to its peers, its fundamentals and, most importantly, its dividend profile.

- There are prices at which a stock is overvalued and should be sold gradually in order to be able to reinvest in other undervalued names.

- There are prices at which a stock should be held or, if not held, monitored.

This is the essence of our Buy low, sell high, get paid to wait mantra.

Investors would be well served to follow this because, as you can see, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year dividend growth rate columns above are mostly below my required return on each of these positions.

If you want your dividends to grow at an attractive rate, you need to buy stocks at the right price.

If you ended up with this portfolio of stocks over time, waiting to buy those stocks when they were cheap, you’d probably do fine, but today you’d be getting standard stock market returns.

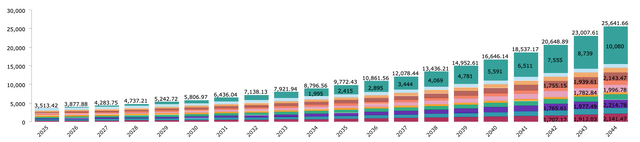

The chart below shows a 20-year income projection from this $100,000 portfolio.

I assumed the dividend growth rates as projected for each of the stocks in my previous article, which I have copied here for clarity:

- AFL: 12%

- GVA: 4.5%

- ADP: 12%

- CVX: 6%

- IBM: 2%

- LOW: 12%

- MCD: 7.5%

- NEE: 10%

- PEP: 6.5%

- O: 3%

The portfolio has a yield of about 3% and a weighted growth rate (relative to yields and weights) of 7%. So I assume dividends are reinvested at this yield and growth rate.

In 10 years, the portfolio would generate annual income of $8,801 and $25,600 per year in 20 years.

Dividend Freedom Tribe

This does not require any additional capital contribution for reasons of simplicity.

In 10 years, the portfolio would therefore return 8.8% of the initial investment, and after 20 years, this return would climb to 25.6% of the initial investment.

While this beautifully demonstrates the power of compounding and shows the power of dividend reinvestment combined with diversification, I think investors would settle for less than they could get.

I would like to see 8-10% of initial income projected over 10 years and 25% over 20 years as a minimum target. And this portfolio exceeds the minimum target.

This also shows how the stock mix works. Add 6% real estate income growing at 3%, to 2% ADP growing at 12%, and the combined result is a 4% yield growing at 5% per year.

But dividend investors who want to maximize their dividend income should take a differentiated approach.

Conclusion: Here’s what you should do instead.

The point of this article, and the previous one, was to demonstrate that the Dividend Aristocrats only guarantee past success, not future success, especially if you want to do better than “good enough.”

If you want to do much better, you have to take a better approach than just buying flagship stocks at any price. You have to know how to manage your timing.

I will conclude this article by explaining how I approach the markets and how I suggest dividend investors do so:

- Don’t get attached to any stock. There is no reason to “like” companies, they are only a means to an end.

- Don’t pay too much attention to dividend history. I like to see a history of consistent dividend growth, but payout ratios, top-line and bottom-line growth, management’s vision all play a much bigger role in determining future dividends than history.

- Charlie Munger said he would rather buy a great business at a fair price than a fair business at a great price. I want both. Give me the great business and the great price. Patience pays off in investing. Find stocks that are clearly undervalued because you can’t change the growth rate you’ll get on your dividends, but you can change the yield by waiting and buying at the right time. The pendulum always swings.

- Let the stock bottom out. In your quest for maximum return on a given stock, you may end up fishing at the bottom. This is a fool’s play. Wait for the stock to bottom out, let it show signs of reversing and regaining momentum before you open the position. You still get most of the profit, and almost none of the pain.

- Hold your shares as long as business is normal, growth is meeting your targets and there is no suggestion that you should sell.

- But if your dividend stocks are extremely overvalued, it makes sense to sell them and reinvest in something undervalued. If you buy a stock that yields 4%, sell it when it yields 2%, and buy another stock that yields 4%, you’ve doubled your income.