The most complete dinosaur fossil ever discovered in Mississippi, called “incredibly unusual” by state officials, remains 85 percent buried since its discovery in 2007.

Paleontologists have confirmed that the specimen was once a living hadrosaur: a family of vegetarian, duck-billed dinosaurs that existed more than 82 million years ago.

But hadrosaurs are a large family of giant herbivores — comprising at least 61 identified individual species, with perhaps hundreds of unique species once roaming the Earth, experts say.

Researchers recovered pieces of the specimen’s spinal vertebrae, parts of its forearm, feet and pelvic bones, but the rest proved difficult to unearth outside Booneville in the northeastern part of the state.

“This thing sat on hold for a while because we didn’t have anybody to work on it,” as state geologist James Starnes admitted.

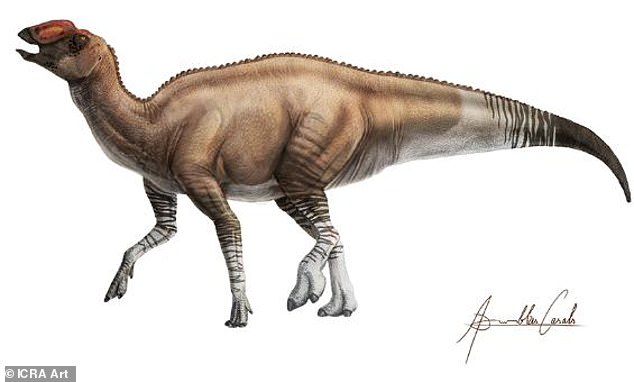

Hadrosaurs are a large family of giant, herbivorous dinosaurs, comprising at least 61 identified and individual species, with perhaps hundreds of unique species once roaming the Earth, experts say. The hadrosaurs above are an artist’s reconstruction of a Russian discovery

The most complete dinosaur fossil ever discovered in Mississippi is now known to belong to the hadrosaur family, but only 15 percent of it has been safely exhumed. Researcher Derek Hoffman (above) turns to 3D analysis of the bones to determine the exact species of hadrosaur

For nearly two decades, it was a mystery which of the many species of hadrosaurs discovered in the Booneville, Mississippi, area was actually the one.

But researchers are now turning to a 3D forensic bone analysis method to solve the puzzle before it is even fully discovered.

Derek Hoffman, a graduate student in geology at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM), is now analyzing the hadrosaur remains using this method, known in many scientific disciplines as “geometric morphometrics.”

“What geometric morphometrics does,” as Hoffman simplified it, “is it takes a form analysis approach.”

Key features or “landmarks” are determined for a given bone sample and their respective distances, as well as the ratios of these distances, are then compared via complex statistical models to confirm differences and similarities with known bones.

This method has also proven useful in anthropology as well as in studies of human evolution, particularly in comparisons between the brain cavities of modern humans and those of our Neanderthal ancestors.

But Hoffman’s search for answers about the hadrosaur fossil is made more difficult by the fact that some pieces of the creature are in the hands of private collectors.

Above, the upper arm bone of an ancient hadrosaur discovered in northeastern Mississippi

Hoffman’s work focuses primarily on bones held publicly by the Mississippi Museum of Natural Sciences.

“We have a good number of vertebrae,” George Phillips, the museum’s curator of paleontology, told the local Clarion Ledger newspaper. “We have a humerus.”

“We have an ulna. The ulna is the posterior part of the forearm.”

“We have some foot bones,” Phillips continued. “And then we have the pubic bone.”

The ulna of an adult hadrosaur is about 60 cm long and its humerus is about 45 cm long. And the foot bones of an adult hadrosaur can weigh over 25 kg alone.

But the dinosaur’s skull — the most unique identifying feature that helps differentiate hadrosaur species — has yet to be located, much to the frustration of researchers.

It is well known that different species of hadrosaurs evolved a wide and strange variety of crowns on their duck-billed heads, and even a soft material like a rooster’s red “comb.”

Paleontologists still debate what biological purpose these unusual and sometimes ostentatious features may have served, but their variety has contributed to the recorded diversity of the hadrosaur family.

USM’s Hoffman focused on the dinosaur’s pubis, a bone located at the front of the pelvis, as the best bet for identifying the fossil’s species.

Although the differences between the pubic bones of hadrosaur species are subtle, often too subtle for the naked human eye, their hidden distinctions can be revealed by rigorous mathematical approaches such as geometric morphometrics.

The USM geology graduate student hopes to at least narrow down the number of potential hadrosaur species that this Mississippi fossil could be.

Or: “What is the lowest level of taxonomy that we can take this hadrosaur to,” as Hoffman put it.

What is now known about this particular hadrosaur is that it was probably about 25 to 26 feet long and stood about 16 feet tall when perched on its hind legs.

According to Hoffman, hadrosaurs are “without a doubt the best-represented dinosaurs in the fossil record.” Pictured: An artist’s impression of another duck-billed dinosaur from this group, dating to 80 million years ago and discovered nearby in Texas

Although researchers believe the hadrosaur lineage began in North America, the herbivores eventually migrated across the globe, with fossils found in Asia, South America, Europe and North Africa.

“They are without a doubt the best-represented dinosaurs in the fossil record,” Hoffman said.

The name hadrosaurs derives from ancient Greek and means “robust lizard,” and the heavy animals actually ranged from approximately 2.2 to 4.4 US tons (or between 2,000 and 4,000 kilograms).

Many species of hadrosaurs lived between 75 and 65 million years ago during the late Cretaceous period.

Other examples of dinosaurs from the hadrosaur family include the Parasaurolophuswhich had a long, backward-curving crest on its head and appears in the 2022 film “Jurassic World Dominion,” and the Edmontosauruswho had the aforementioned crest made of soft tissue like a rooster.

James Starnes, a state official with the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality’s Geology Bureau, said the discovery of the hadrosaur in 2007 near Booneville was just a “‘incredibly unusual.’

“We don’t have a lot of skeletons,” Starnes said. “We have bits and pieces, but no skeletons.”

Starnes hopes that, despite the nearly two decades it took to unearth even a fraction of this hadrosaur fossil, the project will one day be completed.

“We’re continuing to extract more from this specimen,” Starnes said.