Nearly one in three Americans take multivitamins daily, with the primary motivation being to maintain or improve their health. Studying the effectiveness of multivitamins in the “real world” is complicated by the healthy user effect: People who take vitamins tend to eat healthier diets, exercise more, and smoke less. There is also the sick user effect, which may play a role, in that patients with a diagnosed illness may increase their multivitamin intake because of perceived benefits.

A new study examines the risk of death from daily multivitamin use by analyzing three different U.S. populations in which use was assessed repeatedly over an extended period of time, with health outcomes tracked. It was a massive study of more than 390,000 adults, and 164,000 deaths were reported.

The study

This was not a new clinical trial. It was led by Erikka Loftfield and researchers at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and was published on June 26, 2024 in JAMA Open network. Participants in this analysis were selected from the National Institutes of Health–AARP (NIH-AARP) Diet and Health Study cohort (initially, 550,596 AARP members aged 50 to 71 years); the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial cohort (65,577 participants, aged 55 to 74 years); and the Agricultural Health Study (AHS) cohort (57,333 participants aged 18 years and older). After exclusions based on data quality, further exclusions included individuals with extreme caloric intake or those with chronic diseases. The final population available for analysis was 390,124 adults, with trial entry as early as 1993! The median age was 61 years, and the cohort was 55% male.

In all three trials, participants were asked at baseline and at follow-up about their supplement use. Those who responded “Yes” were asked about the frequency of their multivitamin use using predefined categories. Multivitamin use categories were harmonized into three groups: nonusers, nondaily users, and daily multivitamin users.

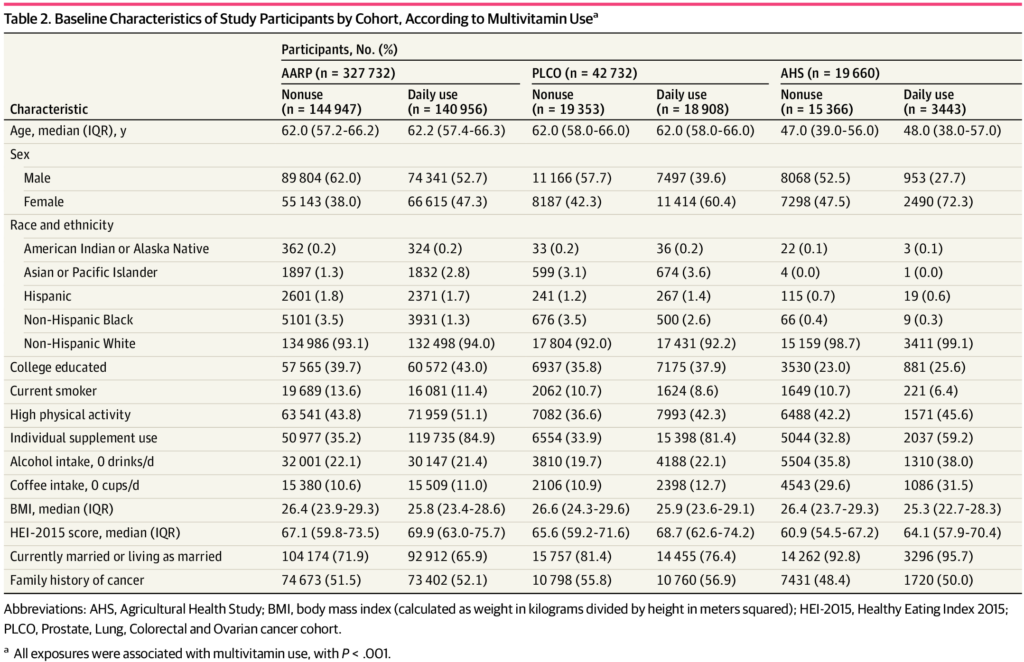

As I noted above, there are many potential confounders that the authors attempted to adjust for across studies, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, smoking status/intensity, BMI, marital status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, coffee consumption, use of other supplements, Healthy Eating Index, and family history of cancer.

Participants were followed from study entry until the date of death, loss to follow-up, or study period closure. Cause-specific mortality was determined from death certificates. The initial results of the three different studies were similar, so the pooled analysis formed the basis of the overall conclusions. Although confounding was minimized, since these were observational data, it is possible that there were unmeasured/unadjusted confounders that were not accounted for.

Results

Across all three cohorts, daily multivitamin users and nonusers were comparable with a few differences:

Participants who took multivitamins were more likely to use individual supplements, have lower BMIs, and have better diets than nonusers. Multivitamin use did not vary significantly by race/ethnicity or family history of cancer.

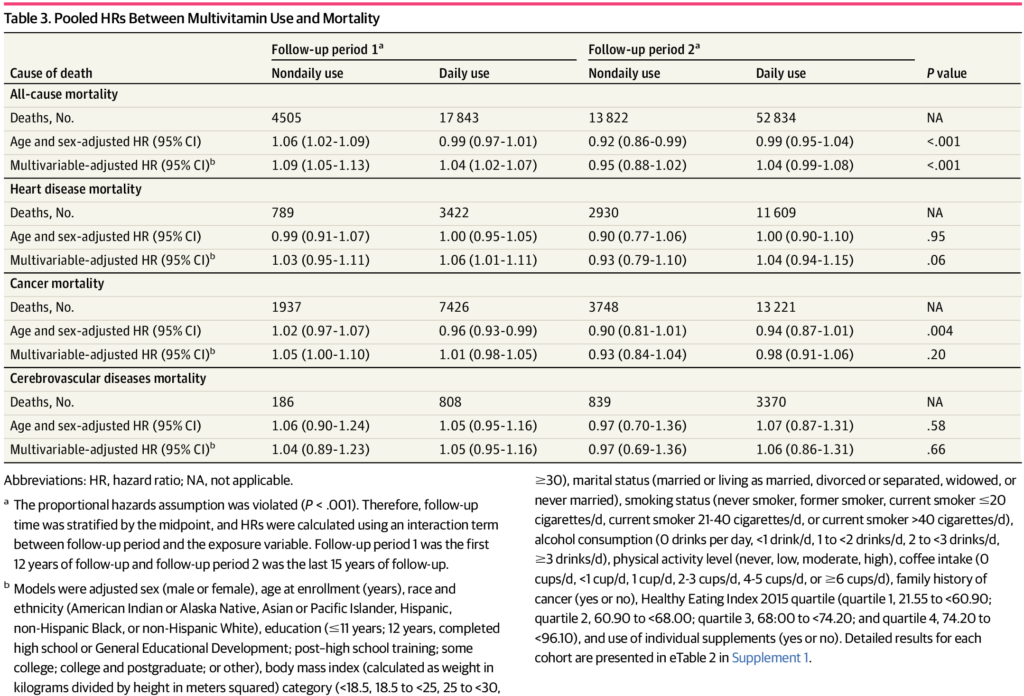

As for effectiveness? Daily use of multivitamins has been associated with a upper risk of mortality compared with non-users (hazard ratio 1.04, 95% confidence interval 1.02-1.07). That is, mortality was 4% higher among multivitamin users. No differences were observed in mortality for heart disease, cancer, and cerebrovascular mortality:

No Justification for Daily Multivitamins

There is no doubt that vitamins play a vital role in health. Supplementation is justified and evidence-based in certain circumstances, such as folate supplementation during pregnancy. However, supplementation is not always beneficial – look at the harm caused by beta-carotene or vitamin E supplements. multivitamin supplements Multivitamins have also been questioned for years. While many people take multivitamins as “insurance” against a diet that may not be optimal, there is no evidence that general multivitamins offer significant benefits.

Given how often Americans take multivitamins, it is important to understand their health effects. This massive study with over 20 years of follow-up showed that there is no clear rationale for routine multivitamin use in healthy adults. On the contrary, multivitamin users appear to be slightly more likely to die Vitamin supplements are less effective than non-consumer vitamin supplements. An accompanying editorial points out that mortality effects, such as those studied in this study, may be obscuring other health benefits, such as age-related macular degeneration, with specific supplements. While this is true, it reinforces the need for targeted, science-based supplementation when the evidence supports it, rather than indiscriminate multivitamins.

The dietary supplement industry has lied to consumers that vitamin and mineral supplements are beneficial to health and that more is better. None of this has been definitively proven to improve longevity. It is now clear that multivitamins as dietary “insurance” are a strategy that is at best useless and at worst, results in reduced life expectancy.