Designing for the human experience is at the heart of architects’ intentions and motivations. While traditional processes are proving beneficial, the industry is scanning the boundaries for opportunities to collaborate with other design fields and disciplines. New approaches have emerged with architects collaborating with service designers and even psychologists to create more human-centered spaces. A new intersection is capturing the attention of practitioners, most recently with a recent installation at Salone de Mobile: neuroarchitecture. ArchDaily explores the scope and potential of this new field with Federica Sanchez, an architect and neuroscience researcher at Italian firm Lombardini22, responsible for the Salone’s renovation.

Neuroarchitecture positively influences traditional practices, often focused on aesthetics, functionality, and code compliance, by emphasizing well-being in design considerations. Essentially, this hybrid approach recognizes that the human brain is intimately connected to the environments in which it operates. “Our body and brain are in constant communication. Interactions between external stimuli and sensory organs are converted into electrical signals, and the body sends sensory information to the brain,” explains Sanchez. This emerging discipline bridges neuroscience and spatial design to challenge perceptions of how a building influences human emotions, thoughts, and actions.

“Traditionally, spaces were designed based on artistic concepts, and then the effects on human perception and behavior were observed. Neuroarchitecture reverses this approach by first understanding how the brain processes the built environment, and then using this knowledge to consciously develop evidence-based designs supported by empirical data,” Sanchez emphasizes. While architectural training can instill a particular theoretical perspective, neuroarchitecture considers how diverse individuals subjectively perceive spaces, avoiding bias. Harnessing neuroscience enriches design intuition rather than diminishing it. With this new understanding, prioritizing human-centered design becomes an ethical imperative that architects cannot ignore.

Related article

How environmental neuroscience is shaping architecture and urban planning

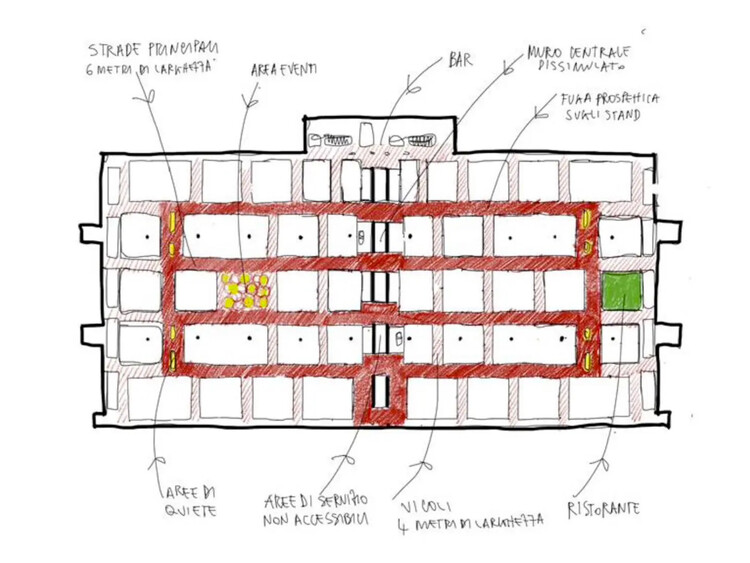

At Salone del Mobile 2024, Lombardini22 designed the exhibition layout in collaboration with neuroscientists. Drawing on their understanding of how grid floor plans influence visitor fatigue and disorientation, the team proposed an evidence-based layout that facilitated natural movement by applying research on human navigation, spatial memory formation, and cognitive mapping of environments. The design aimed to align spatial and temporal experiences to shape visitor journeys. Iterative virtual reality experiments informed the design process, while on-site data collection after implementation demonstrated that the neuroscience-driven layout improved visitor orientation and recall, and reduced cognitive strain.

In early 2019, Lombardini22 launched a research project in collaboration with a team of neuroscientists to study the effects of architectural space on underlying human emotional states and social cognition. The study found that open and spacious spaces promote relaxation and positive feelings, while cramped or confined environments can trigger physiological stress and negativity. This highlights the profound implications of designing spaces that promote empathy, attention, and positive social interactions, making a strong case for neuroarchitecture.

Longoni points to the broad applications of neuroscience in architecture, from hospitals designed to speed patient recovery to office spaces that enhance cognitive performance. Neuroarchitecture holds particular promise in spaces inhabited by vulnerable populations, such as prisons, where design choices can have a significant impact on rehabilitation outcomes and recidivism rates. For example, the renovation of an Italian prison required architects and psychologists to work together to unpack the phenomenological experience of inmates and staff. By isolating the spatial features that elicit specific emotional and behavioral responses, the design team was able to focus their strategies on creating an environment that fosters rehabilitation and personal growth. “The integration of neuroscience is more than just a tool; it’s a paradigm shift that places human experiences and well-being at the heart of the design process,” Sanchez says.

The successful integration of neuroscience into architectural practice relies on effective collaboration between architects and scientists. However, this interdisciplinary exchange is not without its challenges. Differences in methodologies, timelines, and communication styles between the two disciplines can create barriers to the smooth translation of knowledge. Sanchez notes that “generalizability is always a limitation to the translation of scientific findings into design practice: the ability to recreate experimental conditions in other contexts and ensure that the effects will be the same as those obtained in previous studies.”

On the one hand, the scientific process is rigorous and methodical, relying on extensive experimentation, data collection, and peer review to validate findings. On the other hand, architectural design often follows a more intuitive and creative trajectory, shaped by conceptual visions and aesthetic sensibilities. Barriers to knowledge exchange have also been identified as significant challenges. Traditional academic culture, where research findings are shared openly, is known to contrast with the competitive nature of the private sector, in which proprietary knowledge is often closely guarded. Collaboration between neuroscientists and architects requires a collaborative environment that benefits both disciplines.

Additionally, the disconnect between the time required for structured scientific studies and experiments and the usual pace of design processes familiar to architects and clients is a concern. However, the upfront investment of time to test design options could potentially lead to cost savings for property owners once projects are completed. Balancing these different approaches requires open-mindedness, patience, and a willingness to embrace new perspectives on both sides.

Neuroarchitecture offers strong opportunities to radicalize architectural design by grounding it in empirical data and a deeper understanding of human cognition and behavior. The interdisciplinary approach allows architects to proactively design spaces based on how architectural components affect people, leading to more conscious and evidence-based design. Informed design decisions prioritize human well-being to positively impact perception, emotional states, and behavior.

The growing connection between neuroscience and architecture reflects a broader societal trend: the shift toward evidence-informed decision-making. This dialogue reinforces architecture’s position as a rigorous and innovative discipline that prioritizes human well-being. To realize its full potential, architects must facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration across disciplines. By integrating insights from neuroscience, psychology, anthropology, sociology, and behavioral sciences, architecture is revolutionizing its approach, making human experience the primary focus of design and creating built environments that support the intricacies of human life.