Rashida Jones had a disturbing encounter with a Furby in the 1990s.

Her sister’s talking bird toy suddenly started saying lines that didn’t match what it was programmed to repeat. Frightened, they threw the colorful ball of fur outside. The idea of having a seemingly sentient robot around still unsettles Jones.

“I don’t have Siri or Alexa,” she said. “I’m sure they’re listening to me anyway, but I’m not ready to invite a full-fledged computer into my home with access to all of these information-gathering tools just yet.”

Ironically, that’s exactly what her character, Suzie Sakamoto, reluctantly does in the near-future dark comedy “Sunny,” an A24-produced series that premieres Wednesday on Apple TV+.

In “Sunny,” Suzie Sakamoto (Rashida Jones) learns that her husband, Masa, and their son were on a plane that crashed.

(Apple TV+)

Suzie, an American living in Japan, learns that her engineer husband Masa (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and their young child are likely victims of a plane crash. Grieving alone in the historic city of Kyoto, she is visited by one of Masa’s colleagues, who delivers Sunny, a cheeky robot Masa designed specifically to anticipate her emotional needs, and reluctantly accepts her. The more time Suzie spends with Sunny, the more revelations about her origins surface.

“Sunny” was adapted from Colin O’Sullivan’s 2018 novel “The Dark Manual,” and showrunner Katie Robbins was intrigued by how the protagonist, for whom human connection has caused so much heartache, might find a kind of security blanket in an android companion.

One of Robbins’ first changes to the series was to make the robot an ally rather than an antagonist. She also changed the gender of his voice from male to female.

“I’ve been doing research in this area of robotics called HRI, or human-robot interaction, which studies ways that robots can be emotional support systems for people,” Robbins said in a Zoom interview. “A robot is not going to break up with you, break your heart or die.”

For all the potentially beneficial uses artificial intelligence could have for humanity, Jones is concerned about how it already threatens the livelihoods of those in creative professions, including actors.

“Can a person be intellectual property? If a person can’t be copyrighted, you’re going to have to create an AI version of yourself and own that version,” Jones said, speculating on the scenarios. “There are a lot of questions about ownership and identity. It’s scary.”

Hidetoshi Nishijima, left, with Rashida Jones, who asked, “Can a person be intellectual property?”

(Yosuke Demukai / Apple+)

Five years ago, when Robbins began working on “Sunny,” AI wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is today. Robbins worked with an AI consultant early on in the process and remembers thinking some of the concepts she was learning were straight out of the world of science fiction. And then, as the show was being filmed, ChatGPT became available.

“As a species, we’re in a strange situation with artificial intelligence. It’s here to stay, and we have to decide are we going to let it improve our lives or are we going to let it take over?” Robbins said. “I’m a writer, so these questions are very close to my heart.”

Jones said humanity’s interest in AI is inevitable, even fatal, because we have always been obsessed with understanding what it means to be human. Every creative quest, she said, is about proving to ourselves and others that we are meant to be here and that we are special beings on this planet.

“We’re expressing our feelings about our own humanity by creating this thing that seems to resemble us,” Jones said. “It feels like a very dangerous therapy session.”

His on-screen partner, Nishijima, best known in the West for his starring role in the Oscar-winning film “Drive My Car,” said he would welcome a robot that could perform menial household tasks. But he doesn’t want AI to replicate human emotions or try to replace human touch.

“Do you invite just any stranger to your home?” Nishijima asked over Zoom in Japanese through an interpreter. “It’s basically the same thing. I’ll be more careful because I don’t want to spend intimate time with someone I don’t know.”

Nishijima said he identifies with Masa because he majored in engineering in college and because, in the 1980s, the actor’s father was a researcher studying the early stages of artificial intelligence.

“My father used to say that AI research is basically about trying to understand and study human beings,” Nishijima said. “Masa is trying to develop a robot, but what he’s really doing is trying to better understand the human mind and human relationships.”

Nishijima compared the desire to see humanity reflected in our creations to the way people have anthropomorphized toys. “Maybe when humans made the first doll a long time ago, even if it wasn’t great, they thought it had a soul,” he said. “That’s our nature.”

Jones said humans are programmed to feel empathy for humanoid entities like Sunny.

“There’s something interesting about the embodiment of AI, because right now we’re just interacting with intellectual concepts online and sending messages,” she said. “But as soon as we have something with big eyes that blinks and makes an expression, we very easily get the impression that this thing has sentience.”

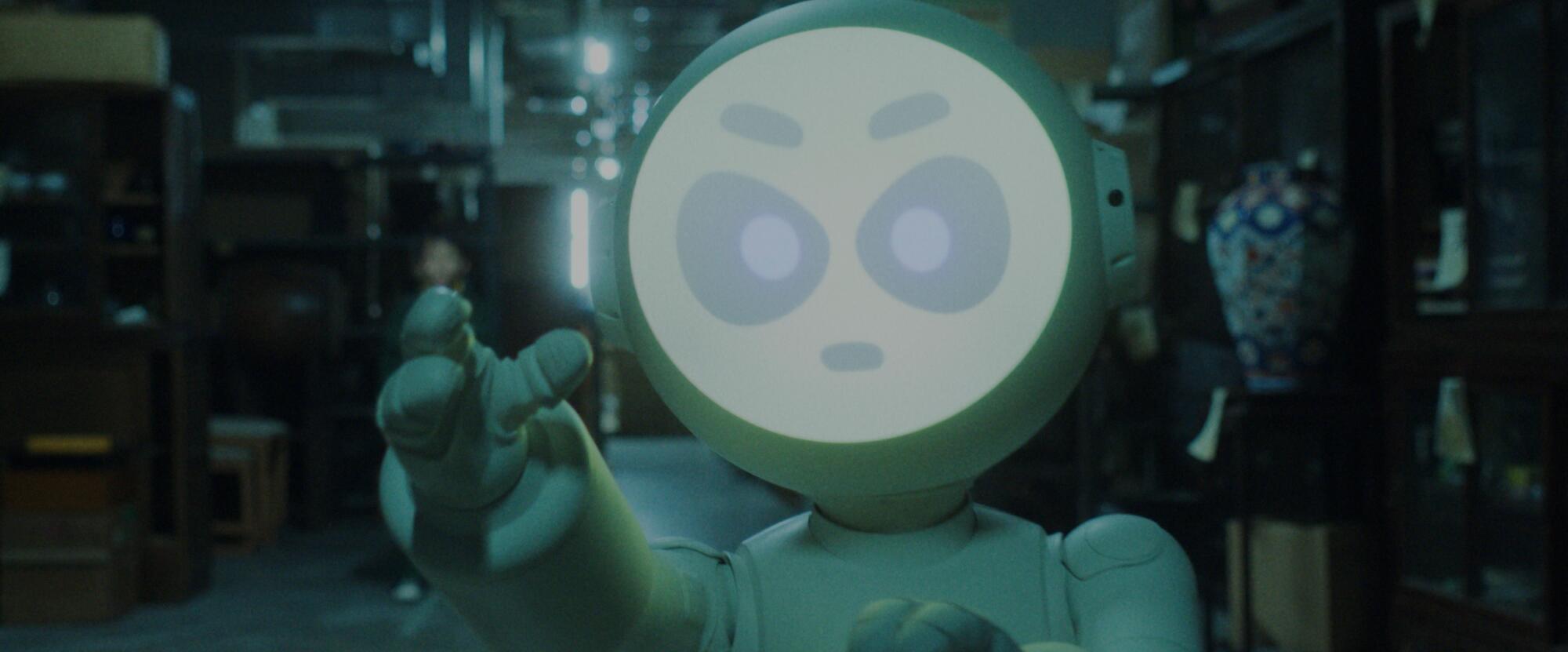

To avoid having the actors play a role that resembles a tennis ball or other Sunny stand-in, the production worked with Weta Workshop in New Zealand — the company of “Lord of the Rings” director Peter Jackson, who created the groundbreaking visual effects for the “Avatar” films — to create an animatronic Sunny puppet.

Tasked with playing Sunny, actress Joanna Sotomura was on set during filming and wore a high-tech helmet that allowed her to see the person she was playing via a camera in the animatronics. In turn, Sotomura’s facial expression was captured in real time and projected onto Sunny’s helmet-like face for the other performers to react to.

Actress Joanna Sotomura played the role of robot Sunny through a headpiece that also captured her facial expressions.

(Apple TV+)

“This show is about a relationship between a woman and a robot, so we wanted Rashida and the other actors to have a physical scene partner,” Robbins said. “It brought authenticity to all of these interactions.”

“If Sunny moved his head a little bit, it really touched me,” Nishijima said. “It really touched me as an actor, because I felt like Sunny really had a soul.”

The series also alternates between English and Japanese, and to bridge the language barrier, Robbins has the characters use an in-ear device, which did not exist in the source material, that allows for simultaneous translation. Suzie does not need to learn Japanese, and even though everyone understands her and vice versa, it keeps her isolated.

Such a device would have been useful in real life, Robbins said. The crew that worked on the series was American and Japanese, and the cast was mostly Japanese. The series used multiple performers on set, and translating the script required meticulous attention to tonal nuances.

“Even this small device reflects many of the themes we’re dealing with: technology is both a force for connection and something that keeps us apart,” she said.

Despite its positive applications, we still don’t know if artificial intelligence could develop its own consciousness independent of its programming. Could Sunny become a rebel? Jones thinks AI could prove to be as unpredictable as humans.

“Because of the desperation that Suzie faces when Sunny comes into her life, it’s like she has no choice but to accept it,” Jones said. “I wonder if that’s going to be the case for all of us. What’s the desperation that we’re going to face that’s going to make us say, ‘We need to have an AI in our house, and it needs to have a pretty face.’”

While Jones said she wouldn’t buy a robot like Sunny even if it were available, she admitted her position could change as AI becomes more ubiquitous, such as social media.

“It’s very possible that this version of me will disappear and then I’ll have to fit in,” Jones said. “I’ll see you again and say, ‘You know what’s funny? I have a robot housekeeper and we love each other so much.’”