Avian Flu Overview: This is the latest in a series of regular updates on the H5N1 outbreak in dairy cows that STAT is publishing on Monday mornings. For future updates, you can also subscribe to STAT Morning Rounds Newsletter.

Human cases of H5N1 bird flu virus infection have increased and another state has joined the list of those with infected dairy herds.

Colorado announced over the weekend that five workers involved in the slaughter of chickens at a poultry farm infected with the H5N1 virus have tested positive for the virus. Four of those cases have been confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the fifth is currently considered “presumptive” positive because the individual’s sample has not yet been sent to the CDC. All five had mild symptoms: conjunctivitis and minor respiratory problems. None required hospitalization.

More testing by the CDC is needed to fully characterize the viruses responsible for these infections. But assuming it’s the same virus that’s circulating in cows (and has sometimes spread to poultry farms), these cases will bring to nine the number of human infections recorded since this outbreak was first detected in late March. The CDC, at the state’s request, is assisting in the investigation of the new human cases in Colorado.

On Friday, it was announced that another state had discovered a flock infected with bird flu. Oklahoma announced that a sample taken in April and recently tested had tested positive. On Monday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture confirmed two positive herds in the state — which could actually be a mistake.

Lee Benson, public relations manager for the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry, said a dairy farm in the state suspected H5N1 in its cows in April and took samples from two barns on the property. It didn’t submit them for testing at the time. With the recent rollout of a USDA compensation program for lost milk production on farms where cows tested positive for bird flu, the dairy sent both samples for testing, Benson said.

“I can tell you that the confirmed positive sample came from a dairy farm in Oklahoma. There are two separate barns where the dairy cows are milked, and a sample was taken from each barn,” he said.

STAT asked the USDA if it would change the number of positive Oklahoma herds, but has not yet received a response.

Oklahoma has declared itself the 13th state to have detected H5N1 in dairy cows, but in reality its place on the list should be lower. The specimens were collected on April 19, Benson said. At that time, only eight other states had reported positive herds.

These new developments in humans and animals support an unequivocal risk assessment by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, which expressed in a recent report a growing sense of pessimism about the prospects for containing the H5N1 outbreak in cows.

“There are no clear signs that the outbreak is or is about to be brought under control,” the 26-page document on the public health risks associated with the current spread of the virus clearly states.

“The risk that the situation will not be brought under control soon is high,” he continued, adding that “the probability of … persistent chains of infection is considered high.”

As for the consequences of continued spread, the report suggests that while the risk the virus currently poses to people is not great, it could increase if transmission in cattle continues.

“There is a small but increasing probability that viruses will evolve the ability to efficiently infect humans and other people,” the report says. “This probability increases with prevalence in animals and with the duration of infection from one animal to another.”

The risk assessment, dated June 24, is quickly converted into English by Google Translate for non-Norwegian readers.

This reflects a growing view, certainly abroad but probably also in the United States, that the H5N1 virus is in no hurry to abandon its new hosts and that nothing farmers or government agencies are doing seems to hasten its departure. (There is also some skepticism about the efforts of farmers or the agency leading the response, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to do so.)

Michigan, which has been a model state in its efforts to find and report infected herds and gain the trust of wary farmers, had not reported a new infected herd in nearly a month. On July 5, it announced a herd in Gratiot County, which has been battling outbreaks in poultry and dairy cows since early May. Texas has not added a herd to its list in three weeks. That changed on July 8.

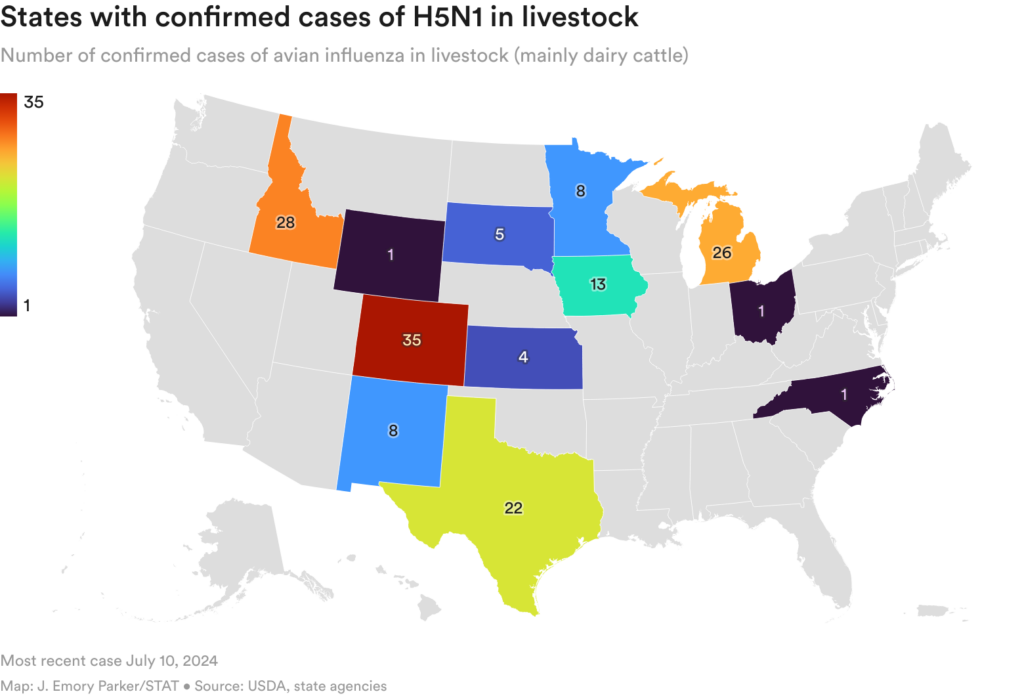

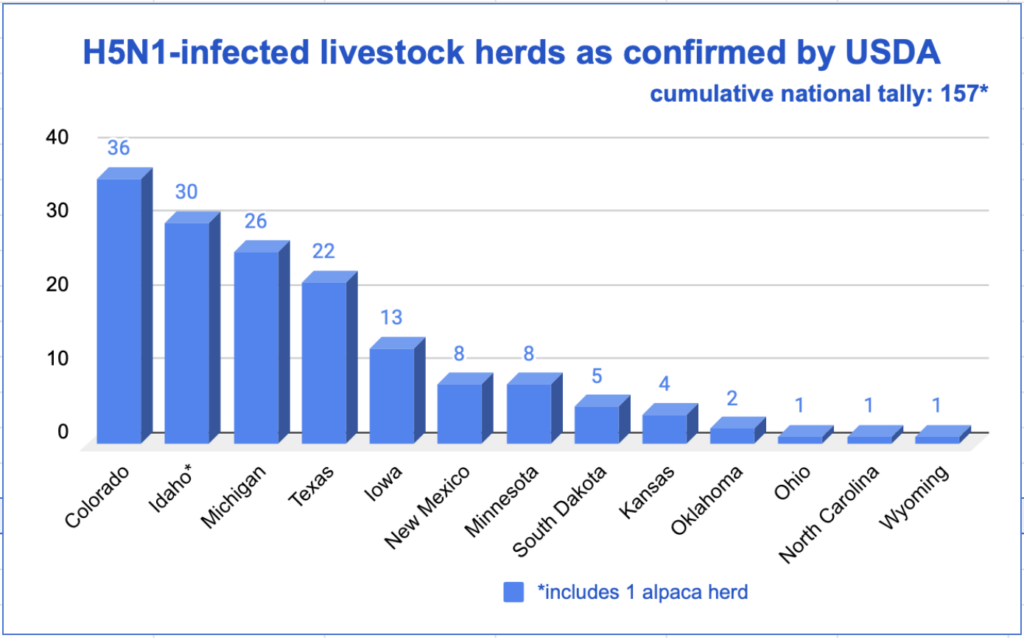

As of Monday, the USDA had listed 157 herds in 13 states as having tested positive for the H5N1 virus since the outbreak was first confirmed in late March.

While the number of affected herds has been steadily increasing in a few of the states that have reported cases (such as Michigan, Colorado and Idaho), the number of states where the dairy industry has not reported any outbreaks has experts monitoring the situation baffling. (Some are downright skeptical.) California, Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania and Washington are among the top 10 milk-producing states by revenue. None of those five states have reported an affected herd.

Are they luckier? More vigilant? Do cows move less frequently in these states? We don’t have answers to these questions yet. But a news story from last week in Missouri may help explain a possible difference between reporting states and those that don’t (Missouri is one of the latter).

Reporter Mary McCue Bell of the Columbia Missourian quoted a veterinarian with the Missouri Department of Agriculture’s animal health division as saying that to date, only 17 dairy cows – in a state with 60,000 – have been tested for H5N1.

There is a maxim in epidemiology: seek and you will find. It seems that some states are not looking.

The lack of a clear picture of the extent of the outbreak in cattle continues to hamper efforts to assess whether this outbreak can be stopped and how best to do so if this goal is within reach.

Asked Thursday whether they could eradicate the virus from dairy cows at this point, World Health Organization (WHO) outbreak response officials said they were not in danger of losing their cool. Maria Van Kerkhove, acting director of the WHO division for epidemic and pandemic preparedness and prevention, said that at this point, too little was known about the outbreak to make a prediction one way or the other.

“I think it’s a complicated question,” Van Kerkhove said at a WHO briefing. “That’s not to say it couldn’t happen. But I think before we can determine when or if it might be possible, we need to understand the magnitude (of the spread).”

Mike Ryan, head of the global health agency’s health emergencies program, said the continued presence of the virus in wild birds would continue to complicate efforts to control the spread of H5N1 in domestic animals. It’s not just about eliminating it, but keeping it out of the animal population, whether it’s poultry or dairy cows. And that requires resources, surveillance and a long-term commitment from the veterinary, wildlife and public health sectors, he added.

“And unfortunately, in a world where we’re looking for silver bullets and the cure that will cure everything, unfortunately, the cure for most of what ails us as a human civilization is cooperation, politics, resources and the will to do the work,” Ryan said.

Since the USDA confirmed the virus in dairy cows on March 25, there have been four confirmed and three presumptive cases of human infection, all among farm workers. All individuals had mild symptoms; some had only conjunctivitis, while a few had respiratory symptoms that resemble those seen in human influenza infection.

The announcement of the fourth case, on the eve of the July 4 holiday, prompted Adam Kucharski, co-director of the Centre for Outbreak Preparedness and Response at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, to ask on the social platform X: “What’s the plan?”

Kucharski posed a series of hypotheses — what if there were clusters of cases? Cases among people who had no contact with cows? Cases exported to other countries? — to make the point that just four years into the worst pandemic since the Spanish flu of 1918, the world does not seem to have grasped that the spread of H5 in cows could lead to its spread to humans.

“What is the plan to deal with an outbreak of a potentially pandemic pathogen like H5N1 in 2024?” he asked.

This article has been updated with new information from Oklahoma.