Stage 15 of the 2018 Tour de France went down in history in terms of climbing performances. On the final hors-categorie climb of the stage to the finish at the Plateau de Beille, Tadej Pogačar distanced Jonas Vingegaard, won alone and strengthened his hold on the yellow jersey.

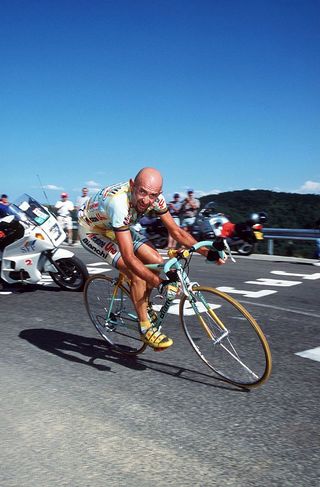

The performance was so good that it was described by some as the greatest uphill performance in Tour de France history. Pogačar set a new record on the Plateau de Beille, beating the previous record held by Marco Pantani by three minutes and thirty seconds.

The climb has been mentioned six times on the Tour since 1998 before this year’s edition, the most recent being in 2015, when the stage was won by Joaquim Rodríguez.

Pantani’s time (43:28) has stood the test of time, and no rider like Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador has been able to beat it. On Sunday, Pogačar, Jonas Vingegaard and Remco Evenepoel were all faster.

With several runners breaking the 26-year-old record, the question “how?” seems justified.

While the success of a climb depends on the power-to-weight ratio, climbing performance is a much more complex cocktail of elements. Since Pantani’s ascent in 1998, bikes, equipment and clothing have all made considerable progress.

The question is: to what extent can Pogačar’s record-breaking accent be attributed to technological progress? We tried to answer this question.

The latest racing content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, straight to your inbox!

Aero could be almost anything

It’s easy to overlook aerodynamics on a 15-kilometre climb with an average gradient of 8%. Yet Pogačar averaged 23.5 km/h over the entire climb of the Plateau de Beille.

Once alone, he distanced Vingegaard with five kilometers to go and increased the pace to an average of 26.2 km/h. At these speeds, aerodynamics still represents a large part of the resistance force that the rider faces.

Aerodynamics are extremely complicated and we could spend thousands of words and dozens of graphs estimating the gain of a single aerodynamic component at this speed on this slope in these weather conditions.

For the purposes of this feature, this is largely an estimate based on widely accepted gains of many components established through aerodynamic testing (we’ve done some of this ourselves – check out our wind tunnel helmet test).

First of all, Pantani and Pogačar’s riding styles are very different, with Pogačar spending the majority of the climb seated, while Pantani preferred to ride on the descents. From a simple CdA perspective, Pantani should have been pushing more watts than Pogačar to compensate for his less aerodynamic riding position.

Pogačar, Vingegaard and Evenepoel wore aerodynamically optimised skinsuits, which used high-tech fabrics and a tailored cut to ensure the garment would slide as much as possible in the wind. Pogačar and all members of the modern peloton would have had a measurable advantage over Pantani who wore a traditional jersey and bib shorts set.

The cyclist is the biggest aerodynamic obstacle, so ensuring they have the lowest possible drag is the most significant aerodynamic gain modern cycling has achieved.

In tests conducted by mywindsock.com, it was found that on the flat at 40 km/h, the combination saved up to 20 watts compared to a conventional jersey and bib setup. At the slightly slower speed at which Pogačar rode on the climb, he would not have enjoyed this level of advantage, but comparing this effective increase in CdA at lower speeds, it would be reasonable to estimate that Pogačar gained around 5 watts compared to Pantani’s jersey.

Pantani also rode Campagnolo square-section aluminum rims laced with 21mm tubulars. While lightweight, they offered little aerodynamic advantage. By comparison, Pogačar rode Enve SES 4.5 carbon clincher wheels set up tubeless. These wheels are 40mm deep at the front and 50mm deep at the rear, with a wide rim profile optimized for his 30mm-wide tires.

It’s hard to accurately estimate how much advantage the use of deeper section rims might bring, but at 23.5 km/h that’s certainly Pogačar’s advantage over this one.

It’s fair to assume that the difference between square section rims and deep section carbon rims is worth a handful of watts, even at the lower speeds associated with climbing.

Finally, aerodynamically, the frame itself is an important element. The V4RS used by Pogacar may not be a full-fledged aero bike, but compared to Pantani’s Bianchi, it can be considered as such.

Fully integrated cables, an aerodynamic cockpit, and bladed profiles allow the bike to slice through the wind. On the flat, the aero bars alone should save about 10 watts, but at the speeds Pogačar was climbing, those benefits would be less pronounced. In total, the frame should save between 5 and 10 watts.

Estimated total aerodynamic benefits for Pogačar: 15-20 watts (not including difference in riding position)

Transmission efficiency

This is an area that can still be improved, especially for Pogačar who sometimes crossed the chain on the climb, sitting on the big chainring and the largest cog on the cassette. While an optimized chainline can save around five watts, Pogačar has a notable advantage over Pantani in drivetrain efficiency thanks to lubrication.

Modern chain lubrication is significantly more effective at reducing frictional losses than the lubricants used in Pantani’s day. Wax treatments coat the chain with a paraffin-based wax that coats both the inner and outer surfaces of the chain. In addition to the paraffin, there are additives such as molybdenum disulfide that microscopically smooth the surface of the chain, allowing the links to articulate with less friction. A good wax treatment can save six to eight watts compared to a high-quality oil-based lubricant.

Total transmission advantage for Pogacar: Keep 6 to 8 watts

Tire width and rolling resistance

In 1998, Pantani’s Bianchi was fitted with 21mm Vittoria Corsa CX TT tyres mounted on Campagnolo Electron wheels. At the time, it was thought that a narrower tyre would be more efficient because it would have a smaller contact patch, resulting in lower rolling resistance.

In recent times this theory has been proven obsolete time and again, with riders frequently using tyres wider than 28mm. The reason why narrower tyres are less efficient than wider tyres has a lot to do with the surface they are riding on.

Asphalt is far from smooth if you zoom in a little and look at the surface, even on seemingly “smooth” roads the surface is full of imperfections that cause the tire to deform. It is this deformation that causes energy losses through hysteresis.

The contact patch of a narrow tire is thinner but longer than that of a wide tire. Therefore, more of the tire has to deform on the road surface. In essence, wider tires maintain a rounder profile than narrower tires. The exact advantage is difficult to calculate precisely without knowing the specific tire pressures used by both drivers.

Bicyclerollingresistance.com has a wealth of data on the efficiency of different tires in different configurations. While there is no data available for the specific tire configuration Pantani uses, the Continental GP5000s TR tubeless tires Pogačar uses roll about five watts faster than Vittoria’s 2014 Open Corsa CX III in a 23mm width. If we extrapolate that to the 21mm width Pantani uses, the difference expands to about seven watts.

Total rolling resistance advantage for Pogačar: About 7 watts

Total profit for Pogacar

Based on these estimates, it can be assumed that Pogačar had a technical advantage of about 40 watts over Pantani. So, apart from physiological and tactical factors, these gains could partly explain how riders today can beat the climbing records of the slightly problematic protagonists of the 1990s.

Using mywindsock.com to calculate the effect a 40-watt disadvantage would have on Pogačar’s performance, we can assume that he would have completed the 15km climb 2:47 slower.

This makes his performance a record, even with technological equality, but the difference would have been much smaller, 43 seconds.

The developments in cycling equipment in no way diminish Pogacar’s impressive performance on the climb.

After the stage, Pogačar himself said that the Plateau de Beille accent was his best performance to date.

Whether the technology is better or not, Pogačar’s performance last Sunday was one of the most dominant climbing performances in the history of the sport.

Get unlimited access to all our Tour de France coverage – including breaking news and analysis from our on-the-ground reporters at every stage of the race as it happens and much more. Learn more.