Four Corners potato tubers in a basket. Credit: Alastair Bistoí

A new study shows that a native potato species was introduced to southern Utah by indigenous peoples in the distant past, making it the only culturally significant plant species to have been domesticated in the southwestern United States.

The team of researchers, led by the Red Butte Garden and the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) at the University of Utah, used genetic analysis to reveal how and where Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii) tubers were collected, transported and traded across the Colorado Plateau. The findings support the claim that the tuber is a “lost sister,” joining corn, beans and squash, commonly known as the Three Sisters, as a staple of crops ingeniously cultivated in this arid landscape.

“Transportation is one of the first crucial steps in the domestication of native plants into crops,” said Dr. Lisbeth Louderback, curator of archaeology at NHMU, associate professor of anthropology at the university and co-author of the study. “Domestication of a plant species can begin with the collection and replanting of propagules in a new location.”

The authors collected DNA samples from modern Four Corners potato populations near archaeological sites and from non-archaeological populations located within the potato’s natural range in the Mogollon Rim of central Arizona and New Mexico. The results indicate that the potato was transported and cultivated, likely by the ancestors of modern Pueblo (Hopi, Zuni, Tewa, Zia), Diné, Southern Paiute, and Apache tribes.

“The Four Corners potato, along with corn, cacao and agave, reflects the significant influence humans have had on plant diversity in the landscape over millennia,” said Dr. Bruce Pavlik, former conservation director at Red Butte Garden and lead author of the study.

The document appears in the American Journal of Botany.

S. jamesii contains twice as much protein, calcium, magnesium and iron as an organic red potato, and a single tuber can produce up to 600 small tubers in just four months. This nutritious crop would have been a highly prized and crucial trade item during the harsh winter months. While the Four Corners potato’s unique distribution surprised scientists and researchers, local tribesmen suspected it all along.

Solanum jamesii plant, the Four Corners potato. Credit: Tim Lee / NHMU

The Lost Sister

The Mogollon Rim region encompasses south-central Arizona and extends east and north to the Mogollon Mountains of New Mexico. Jagged limestone and sandstone cliffs break up the scattered ponderosa pine, pinyon pine, and juniper trees on the high-elevation terrain. S. jamesii is widespread on the Rim: the plants thrive in coniferous forests, and thousands of small tubers may grow under a single pinyon pine canopy. These “non-archaeological” populations are unrelated to artifacts, grow quite large, and are continuously distributed throughout the habitat.

In contrast, “archaeological populations” of potatoes occur within 300 meters of ancient habitation sites and tend to be smaller than in the species’ core range. The scattered and isolated populations of the Colorado Plateau have a genetic composition that can only be explained by human gathering and transport.

To reproduce sexually, that is, to create viable seeds, flowers must receive pollen from another plant with specific, compatible genetic factors. Without the right mate, plants will clone themselves by growing from underground stems to create a genetically identical daughter plant. Its cloning ability allows S. jamesii to persist even when conditions are less than ideal. It also provides a genetic fingerprint that marks the origin of each population. This signature is common in potatoes transported to places where there are few other individuals and persists for hundreds of generations.

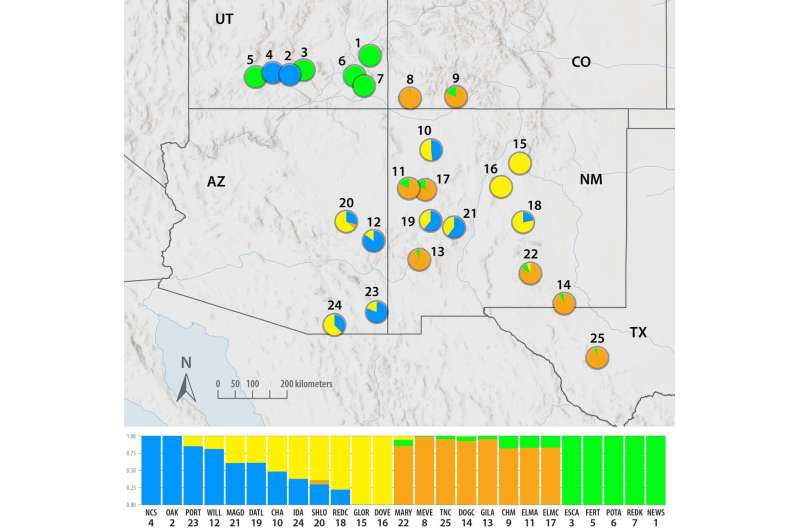

The researchers collected DNA samples from 682 individual plants in 25 potato populations from the Four Corners: 14 populations were near archaeological sites, while 11 were from non-archaeological areas of its natural distribution. The results showed that the most genetically diverse S. jamesii populations were concentrated around the Mogollon Rim. Conversely, populations from archaeological sites had reduced genetic diversity because the transported tubers may have contained only a fraction of the available genes.

In search of the origins of archaeological populations

The authors found that S. jamesii populations in the Escalante Valley of southern Utah have two different origins: one directly from the Mogollon Rim region and one linked to Bears Ears, Mesa Verde, and El Morro. These archaeological sites form a genetic corridor suggesting that ancient peoples transported the tubers.

Map showing genetic structure by ancestry. Each bar represents the genetic makeup of a given potato population and shows where the genes came from. Credit: American Journal of Botany (2024). DOI: 10.1002/ajb2.16365

Despite their geographic proximity, four archaeological populations around the Escalante Valley show distinct origins. Genetic signatures could indicate that people transported potatoes to new locations repeatedly in the distant past, in a pattern that likely corresponds to ancient trade routes.

“The potato is part of a larger set of goods that were traded across this vast cultural landscape,” Louderback said. “For millennia, people in the Southwest participated in the region’s social networks, migrations and trade routes.”

What is certain is that the species was transported and cultivated far from its natural center of distribution. Scientists at the USDA Potato Gene Bank have been sampling the genetics of the Four Corners potato for decades and have been intrigued by the diversity of genetic patterns along its geographic range.

“We’re wondering about the distribution patterns of genetic diversity in Solanum jamesii,” says Dr. Alfonso del Rio, a plant geneticist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Potato Gene Bank and a co-author of the study. “We weren’t sure that humans had changed its range, but now we have evidence that confirms it.”

The researchers interpret the transport of the Four Corners potato as the early stages of domestication. However, they plan to analyze specific genetic sequences to learn more about S. jamesii’s frost tolerance, taste and germination ability, among other things, to understand whether the potato was truly domesticated.

“We would like to study specific genetic markers for certain desirable traits, such as tuber size and frost tolerance,” Pavlik said. “It’s quite possible that indigenous people preferred certain traits and thus tried to encourage favorable genes.”

More information:

Bruce M. Pavlik et al., Evidence for the Human Founder Effect in Solanum jamesii Populations at Archaeological Sites: II. Genetic Sequencing Establishes Ancient Transport Across the Southwestern United States, American Journal of Botany (2024). DOI: 10.1002/ajb2.16365

Provided by the University of Utah

Quote:Genetics Reveal Ancient Potato Trade Routes Four Corners (2024, July 18) Retrieved July 20, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-genetics-reveal-ancient-routes-corners.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.