An old, dilapidated barn, slated for demolition, held a treasure trove for a researcher.

On a tip from his department chair, Andrew Margenot, a soil scientist at the University of Illinois, visited the campus’s agricultural research farm in the summer of 2018.

Even in broad daylight, he had to wear a headlamp to find his way in the dark barn.

“I realized, five minutes into walking through these cobwebs and these very dark hallways, that there were rows and shelves of soil,” Margenot recalls. “And that these were the original soils taken from the mapping of this state.”

The barn contained thousands of soil samples, stored in Mason jars and other sealed containers, from nearly every county in the state. Some of the samples dated back to the 1860s, while the bulk of the collection dated to the early 1900s.

Jim Meadows

/

Harvest Public Media

Margenot said his mind was boggled by the research possibilities.

“I didn’t sleep for about two nights because I was so excited about all the things we could answer,” he said.

Research using soil archives is an emerging field of study, with the number of published papers increasing steadily since the 1980s. While agricultural scientists have been systematically collecting soil samples for decades, the University of Illinois soil archives offer a rare opportunity to track soil changes over the course of a century.

Most soil records only go back three or four decades.

“What’s amazing is that we have a very limited understanding of how soil changes over generations,” said Mark Liebig, a soil scientist who studies soil conditions in the Great Plains states at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory in North Dakota.

“The average human life expectancy today is about 73 years. Except for a few places around the world where soil samples have been collected and sites maintained for research purposes, we don’t really know how the soil changes over that time.”

Liebig believes that some older soil records that existed have been lost. Some may have been thrown away.

But others may have been lost to their institutions, waiting to be rediscovered.

What we can learn from the soil

At Penn State University, soil samples dating from 1915 and 1933 were found in a storage closet at the university’s research farm four years ago.

The collection of 53 clay pots is now housed in the Pasto Agricultural Museum at Penn State.

“I think one of the things that has intrigued me the most about these samples is the conversations between the wide variety of research fields,” said director Rita Graef, “anthropologists, microbiologists and atmospheric scientists who are curious and wondering what we might discover about the contents of each of these jars?”

Pennsylvania State University

/

Creative Commons License

The samples come from a long-running soil fertility study known as the Jordan Soil Fertility Plots, which were active at Penn State from 1881 to the 1950s. Graef said much can be learned from old samples using new techniques, even reviving dormant soil microbes to study their DNA.

“We need to preserve these collections,” Graef said, “because in the future there may be technologies that will allow us to better understand what was happening in the soil at that time, so we can make decisions for the future.”

Today, a parking lot sits on much of what was once Jordan’s plots, making it unlikely that new soil samples will be taken. But these samples are valuable because they contain detailed records of farming practices used over the years.

Todd Lorenz, an agronomist at the University of Missouri, sees an advantage in analyzing soil samples from test plots, where detailed information about farming practices exists.

“You’d almost have to have a crystal ball if you didn’t have the data over time to know what’s going on,” Lorenz said. “So you’d just be guessing.”

Revolutionary research

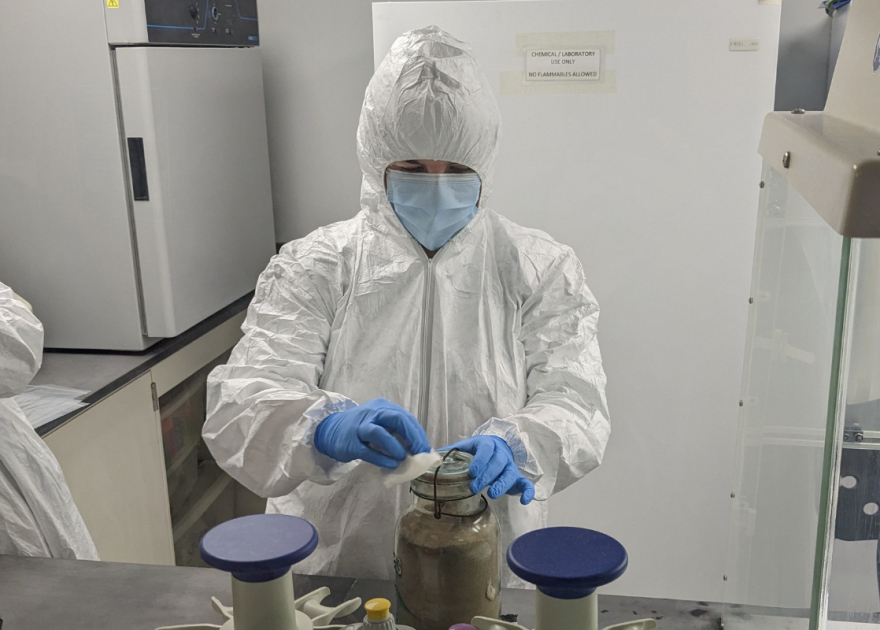

The University of Illinois’ soil sample collection, which includes some 14,000 jars, is now housed in a much newer barn. Margenot said it took him years to get the collection in order and secure funding for research that uses it.

“In terms of the largest and longest archives, this is a gem,” Margenot said, surveying the shelves.

The university lost track of its vast soil archive after the death in 2003 of agronomist Theodore “Ted” Peck, who had built shelves for the thousands of soil samples and installed them in the barn where Margenot found them six years ago.

Margenot is now using location data from more than 450 samples to try to collect new samples from the same locations. He is trying to compare soil samples over a period of up to 120 years across an entire state, which is groundbreaking research.

“What’s unique is the distance covered in time and the vast extent of the area involved, particularly with respect to resampling,” he said.

Jim Meadows

/

Harvest Public Media

So far, he’s been able to collect 60 new soil samples with permission from landowners across the state. A hydraulic probe attached to a tractor takes multiple samples at each site, digging a little more than a meter deep into the soil and collecting samples about two inches in diameter.

Margenot hopes to understand how soil fertility has changed by looking at micronutrients, how much erosion has occurred over long periods of time and how much loss of soil organic matter – which is mostly carbon – has occurred.

“The fundamental question is how much organic matter have we lost over the last 120 years of agriculture. And that can be broken down by soil type. So it’s not just a general question, we can even get a more specific answer at the county level,” Margenot said.

Some farmers are eagerly awaiting its findings.

The collection includes samples from Brad Shippert’s family farm near Dixon, Illinois. Earlier this year, researchers collected new samples from land the family has owned since 1864.

Shippert hopes the results of the new sample analysis can help guide his farming practices.

“If there was a dramatic change in organic matter, for example, you could look at changing tillage practices or crop rotation,” he said. “There are all sorts of small changes that could be made, you know. Are we mixing the soil layers by tilling too deep? You should be able to tell that from those kinds of things as well.”

John Kiefner, who farms near Manhattan, southwest of Chicago, is eagerly awaiting analysis comparing recent samples taken from his land to those from more than six decades ago.

“I see this as a way for me to educate myself more and become a little smarter,” Keifner said. “I’m really curious to see how this soil has changed from 1957 to 2024.”

Kiefner and his father adopted no-till farming more than 30 years ago. He hopes to find that the change has actually improved his soil, or at least not damaged it.

According to Margenot, soil science has a lot of catching up to do compared to other sciences.

He said physics and algebra were studied by the ancient Greeks, while the study of soils is only 100 years old, “if you’re generous and round up.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Mediaa collaboration between public media newsrooms across the Midwest. It covers food systems, agriculture and rural issues.