Researchers believe Order it It may have swum upside down to retrieve food from the many spines along its legs. Credit: Illustrated by Danielle Dufault. Royal Ontario Museum

A new study, led by paleontologists at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), helps unravel the evolution and ecology of Odaraia, a taco-shaped marine animal that lived during the Cambrian Period.

Fossils collected by the ROM reveal that Odaraia had mandibles. Paleontologists are finally able to place it among the mandibles, ending its long and enigmatic classification among arthropods since its first discovery in the Burgess Shale more than 100 years ago and revealing more details about early evolution and diversification.

The study “The Cambrian Odaraia alata and the colonization of nektonic suspension feeding niches by the first mandibles

” was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

The study authors were able to identify a pair of large, jagged-edged appendages near its mouth, clearly indicating mandibles, which are one of the key and distinguishing features of the mandibulated group of animals.

This suggests that Odaraia was one of the earliest known members of this group. The researchers made another surprising discovery: a detailed analysis of its more than 30 pairs of legs revealed a complex system of small and large spines. According to the authors, these spines could intertwine, capturing smaller prey like a fishing net, suggesting how some of these early mandibles left the seafloor and explored the water column, laying the foundation for their future ecological success.

“Odaraia’s cranial shield envelops almost half of its body, including its legs, almost as if it were enclosed in a tube. Previous researchers have suggested that this shape may have allowed Odaraia to herd its prey, but the capture mechanism has eluded us until now,” says lead author Alejandro Izquierdo-López, who was based at the ROM during this work as a PhD student at the University of Toronto.

“Odaraia had been beautifully described in the 1980s, but given the limited number of fossils at that time and its bizarre shape, two important questions remained unanswered: Is it really a mandible? And what did it feed on?”

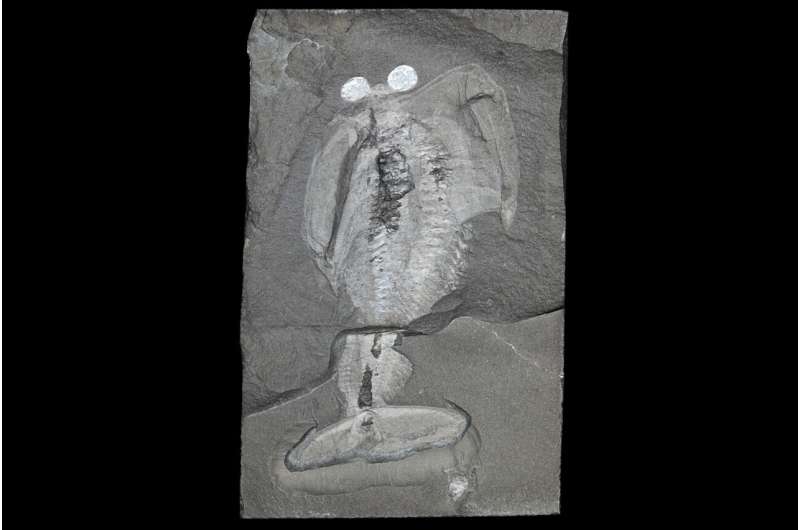

Photos of the Odaraia fossil, ROMIP 60746. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron, Royal Ontario Museum.

Measuring nearly 20 cm, early mandibles like Odaraia were part of a community of large animals that may have migrated from the bottom marine ecosystems characteristic of the Cambrian period to the upper layers of the water column. These types of communities could have enriched the water column and facilitated a transition to more complex ecosystems.

Cambrian fossils provide evidence of the major divergence of animal groups that emerged more than 500 million years ago. This period saw the evolution of countless innovations, such as eyes, legs, and shells, and the first diversification of many animal groups, including mandibles, one of the major groups of arthropods (animals with jointed limbs).

Mandibles are an evolutionary success story, making up more than half of all living species on Earth. Today, mandibles are everywhere—from marine crabs to millipedes that lurk in the underbrush to bees that fly over grasslands—but their beginnings were more humble. During the Cambrian period, the first mandibles were marine animals, most with distinctive skull shields or shells.

Odaraia fossil ROMIP 952413_1. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron, Royal Ontario Museum

“The Burgess Shale is a veritable goldmine of paleontological information,” says Jean-Bernard Caron, Richard Ivey Curator at the Royal Ontario Museum and co-author of the study.

“Thanks to the work we’ve done at the ROM on amazing fossil animals like Tokummia and Waptia, we already know a lot about the early evolution of mandibles. However, other species have remained quite enigmatic, like Odaraia.”

The Royal Ontario Museum is home to the world’s largest collection of Cambrian fossils from the Burgess Shale, a region of British Columbia that is renowned worldwide. The Burgess Shale fossils are exceptional because they preserve structures, animals and ecosystems that, under normal conditions, would have decayed and disappeared entirely from the fossil record.

Mandibles are, however, generally rare in fossils. Most fossils preserve only the hard parts of animals, such as the skeletons or mineralized cuticles of the well-known trilobites, structures that mandibles lack.

For over 40 years, the Odaraia has been one of the Burgess Shale’s most iconic animals, with its distinctive taco-shaped shell, large head and eyes, and a tail that resembles a submarine’s keel. Odaraia specimens are on display for the public at the Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, at the Royal Ontario Museum.

More information:

Cambrian Odaraia alata and the colonization of suspension feeding nektonic niches by early mandibles, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2024.0622. royalsocietypublishing.org/doi….1098/rspb.2024.0622

Provided by the Royal Ontario Museum

Quote:Taco-Shaped Arthropod Fossils Provide New Insights into Early Mandible History (2024, July 23) Retrieved July 24, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-taco-arthropod-fossils-insights-history.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.