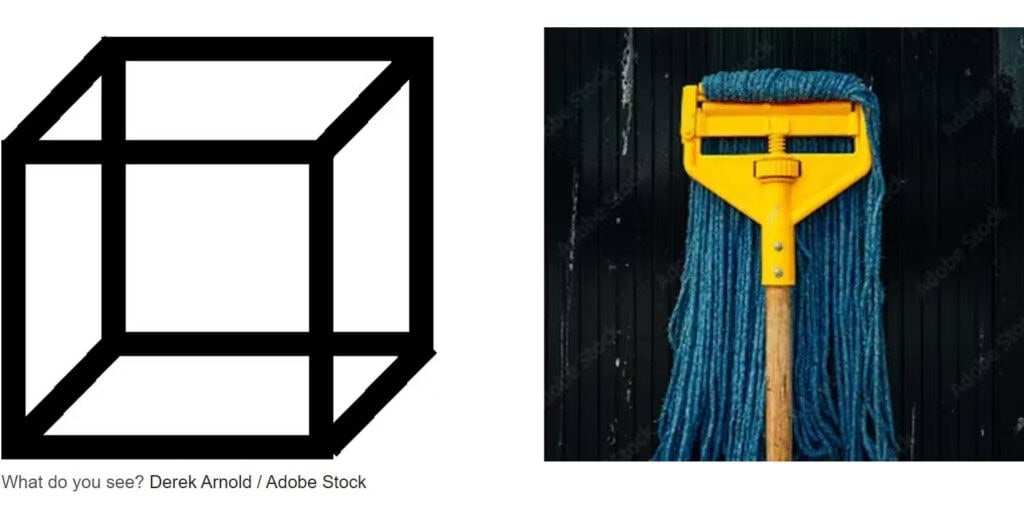

Look at these pictures. Do you see a cube on the left and a face on the right?

Can you imagine seeing things in your mind? Can you hear an inner voice when you think or read?

One of the authors, Loren Bouyer, can’t do any of this. To Loren, the image on the left looks like a jumble of two-dimensional shapes, and she sees only a mop on the right.

Loren cannot imagine auditory or visual sensations or hear an inner voice when she reads. She suffers from a disorder we describe as “profound aphantasia” in a new paper published in Frontiers in Psychology.

“A blind mind”

Both authors are aphantasiac: we are incapable of having imagined visual experiences.

Aphantasia is often described as “having a blind mind.” But often, we cannot have other imaginary experiences either. Thus, an aphantasiac may have a blind and deaf mind, or a blind and tasteless mind.

We are often asked what it feels like to be aphantastic. A few analogies may be helpful.

People have multilingual minds

Most people can hear an inner voice when they think. You may only speak one language, so your inner voice will “speak” that language.

However, you understand that other people can speak different languages. So you can imagine what it would be like to hear your inner voice speaking several different languages.

We can also imagine what our thoughts must be like. They can be diverse and be felt as inner visual or auditory sensations, or as an imaginary sense of touch or smell.

Our minds are different. Neither of us can imagine visual experiences, but Derek can imagine auditory sensations and Loren can imagine tactile sensations. We both experience our thoughts as a different set of “inner languages.”

Some aphantasics report not having any of them imagined sensations. What might their thought experiences be like? We think we can explain it.

Although Loren can imagine sensations of touch, she doesn’t have to. She must choose to feel them, and that takes effort.

We assume that your imagined visual experiences are similar. So what does it look like when Loren thinks, but chooses not to have imagined tactile sensations?

Our subconscious thoughts

Most people can choose to pre-listen to their speech in their head before speaking out loud, but this is often not the case. People can engage in conversation without listening to themselves.

For Loren, most of her thinking is like this. She writes without any prior experience with written content. Sometimes she stops, realizing she’s not ready to add more yet, and starts again when she feels ready.

Most of our brain operations are unconscious. For example, while we don’t recommend it, we think many of you have driven while distracted, only to suddenly realize that you were heading home or to the office instead of your intended destination. Loren believes that most of his thoughts are like these subconscious operations of your mind.

And planning? Loren can experience it as a combination of imagined textures, bodily movements, and recognizable states of mind.

There is a sense of completion when a plan is made. A planned speech is a sequence of imagined mouth movements, gestures, and postures. Her artistic plans are experienced as textures. She never experiences an imagined audio or visual list of her planned actions.

There are big differences between aphantasics

Unlike Loren, Derek’s thoughts are entirely verbal. He was unaware until recently that other modes of thought were possible.

Some aphantasics report occasional involuntary imaginary sensations, often related to unpleasant past experiences. None of us have ever had an imaginary visual experience, voluntary or involuntary, during our waking life.

This highlights the diversity. All we can do is describe our own particular experiences of aphantasia.

The frustrations and humor of misunderstandings

Aphantasics may be frustrated by others’ attempts to explain their experiences. Some have suggested that we may have imagined visual experiences but be unable to describe them.

We understand the confusion, but it may seem patronizing. We both know what it is like to have imagined sensations, and so we think we can recognize the absence of a particular type of imagined experience.

The confusion can go both ways. We were recently discussing an experiment. The study was too long and had to be shortened. So we thought about what imaginary visual scenario to cut.

Loren suggested doing a scenario asking people to imagine seeing a black cat with their eyes closed. We thought it would be difficult to see an imaginary black cat because of the darkness of closed eyes.

The only person in the room who could have imagined visual experiences laughed. Apparently, it’s easy for most people to imagine seeing black cats, even when their eyes are closed.

Deep aphantasia

Researchers believe that aphantasia occurs when activity in the front of the brain fails to stimulate activity in regions in the back of the brain. This “feedback” is thought to be necessary for people to have imaginary experiences.

Loren appears to suffer from a form of aphantasia that has not been described. Unsuccessful feedback in Loren’s brain appears to result in atypical experiences of real visual input. Thus she cannot see the cube at the top of this article, nor the face instead of a broom, nor have a number of other typical experiences of visual input.

We coined the term “profound aphantasia” to describe people like Loren, who not only are unable to have imagined sensory experiences, but also have atypical experiences of actual visual input.

Our goal in describing our experiences is to raise awareness that some aphantasics may have unusual experiences of actual visual seizures, like Loren. If we can identify these people and study their brains, we may be able to understand why some people can conjure up imagined sensory experiences at will, while others cannot.

We also hope that raising awareness of the different experiences people have when thinking might encourage tolerance when people express different thoughts.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.