Now that summer is in full swing, mosquitoes have appeared all over the United States. Using mosquito repellents can protect both your health and your sanity this summer.

Mosquitoes leave annoying and irritating bites on your skin, but they can also pose a serious, even deadly, risk to your health. When a mosquito bites you, it can transmit dangerous pathogens that cause dangerous diseases like malaria, dengue fever, Zika virus, and West Nile virus.

Avoid mosquito bites

Female mosquitoes bite people to get essential nutrients from our blood. They then use these nutrients to make their eggs. A single blood meal can produce about 100 mosquito eggs that hatch into wriggling larvae.

There are several ways to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes, such as wearing long, loose clothing and limiting time spent outdoors, placing screens on your windows, and eliminating standing water that mosquitoes could use to breed.

However, one of the best ways to protect yourself when you’re traveling to a place where hungry mosquitoes are buzzing is to use mosquito repellents.

Our team at the Molecular Vector Physiology Lab at New Mexico State University has been studying different types of mosquito repellents and their effectiveness for over a decade. Here’s what you need to know to protect yourself this summer:

All about repellents

The use of mosquito repellents goes back a long way in history, and certainly predates written historical accounts. Some of the earliest evidence of the use of mosquito repellents dates back to the time of ancient Egypt and Rome. At that time, the smoke from fumigation fires was often used to repel mosquitoes.

Today, we have more options than our ancestors when it comes to choosing the type of mosquito repellent to use: sprays and lotions, candles, coils and vaporizers, to name a few.

These repellents interfere with mosquitoes’ senses of smell, taste, or both. The repellent blocks or overstimulates these senses. Scientists understand how some repellents like DEET work at the molecular level, but for many, it’s still unclear exactly why they repel mosquitoes.

Testing repellents

We conducted a variety of scientific experiments in the lab and field tests to determine what works. For some products, the tests simply involved placing a volunteer’s treated arm in a cage with 25 mosquitoes and waiting for the first mosquito bite.

For others, like citronella candles, we used a low-speed blower and placed a candle or device between a person and a mosquito cage. Depending on how effective the device was at repelling mosquitoes, they would either fly toward the person or away. Another experiment we ran was the Y-tube choice test, where mosquitoes would choose to fly toward someone’s hand or, if repelled, fly toward the empty option.

Mosquito Repellents That Don’t Work

Bracelets are not effective. Department stores and drugstore chains sell hundreds of different varieties of bracelets. They are marketed as “mosquito repellent” bracelets, wristbands, and watches, and their materials can range from plastic to leather. Even if they are loaded with repellent, they cannot protect your entire body from mosquito bites.

Ultrasonic repellents don’t work. They come in the form of electrical plugs, stand-alone models, or watch-like accessories that claim to emit a high-frequency sound that deters mosquitoes by mimicking bats. However, scientific studies have shown that ultrasonic repellents fail to repel mosquitoes. In fact, when our lab tested one of these devices, we saw a slight increase in mosquito attraction to the wearer.

Dietary supplements – vitamin B, garlic, etc. – are not effective. There is no scientific evidence that these supplements protect against mosquito bites.

Light-based repellents don’t work. These devices come in the form of colored bulbs and don’t attract insects that fly toward white light. This approach works well on moths, beetles, and stink bugs, but not on mosquitoes.

Effective mosquito repellents

And here’s our ranking of what works, starting with the best repellent/active ingredient.

-

DEET is effective. DEET, whose chemical name is N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide, was developed in the 1950s by the U.S. military and is a well-established mosquito repellent that has been in use for a long time. The higher the percentage, the longer the protection, up to six hours.

-

Picaridin is effective. This synthetic repellent can protect for up to six hours at a concentration of 20%. This repellent is a promising alternative to DEET.

-

Oil of lemon eucalyptus, or OLE, is effective. OLE, whose active ingredient is PMD, is a plant-based alternative to DEET and picaridin. Its repellent properties can last up to six hours.

-

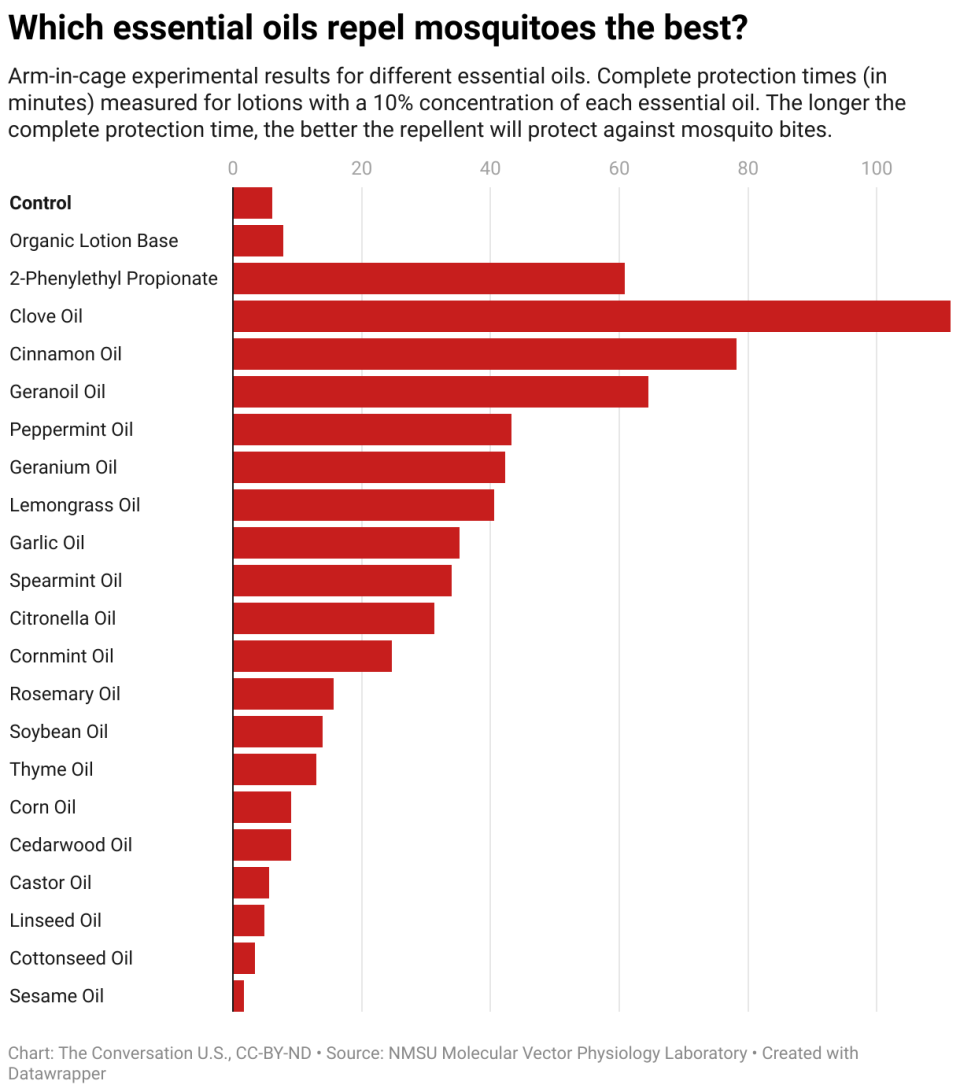

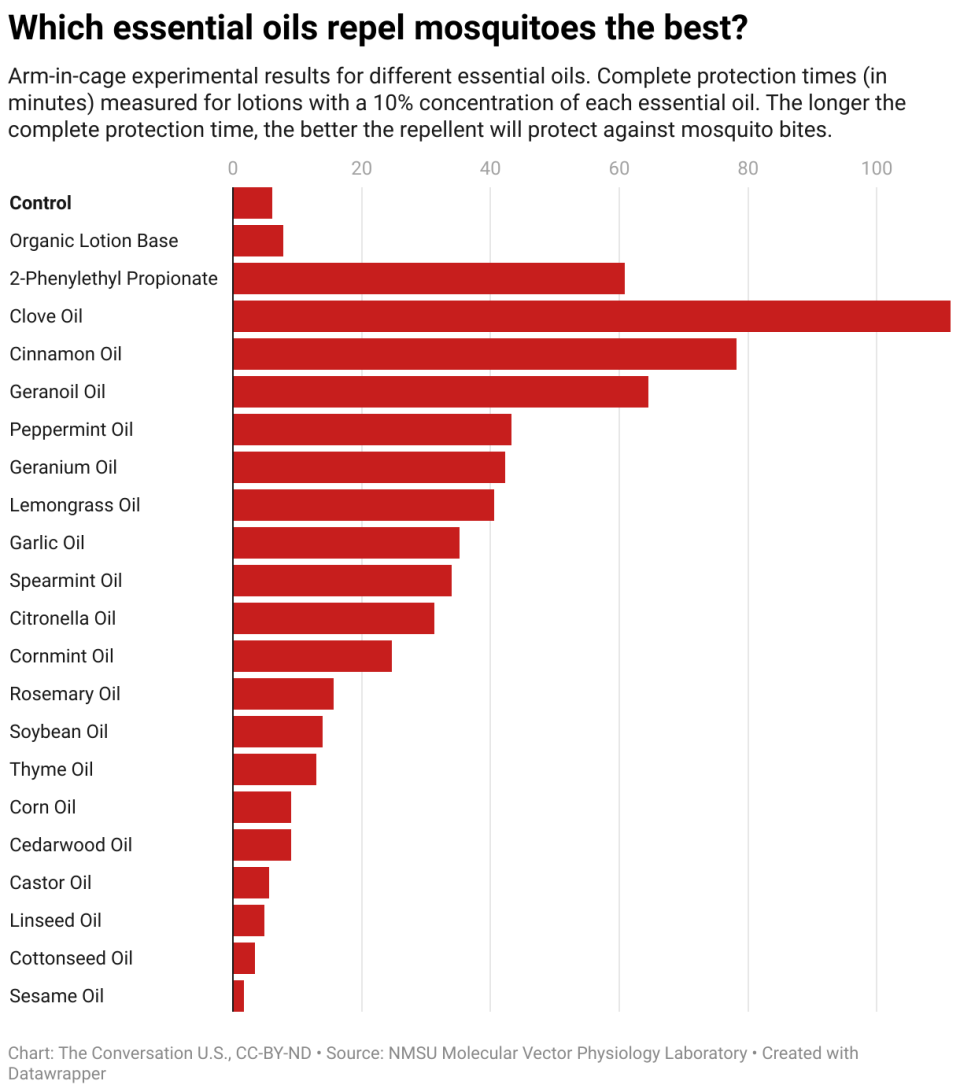

Other essential oils – some work, some don’t. We applied 20 different essential oils in a 10% essential oil lotion blend to the skin of volunteers. Here’s what we found:

Clove oil is effective. This oil, which has the active ingredient eugenol, can protect against mosquito bites for over 90 minutes at a 10% concentration in a lotion. Cinnamon oil is effective. This oil, which has the active ingredients cinnamaldehyde and eugenol, can protect against mosquito bites for over 60 minutes at a 10% concentration in a lotion. Geraniol and 2-PEP, or 2-phenylethyl propionate, work for about 60 minutes at a 10% concentration in a lotion. Citronella oil is effective, but not as effective. We found that 10% citronella oil only protected against mosquito bites for about 30 minutes.

If you’re planning on making your own herbal mosquito repellent this summer, keep in mind that essential oils are complex mixtures of chemicals made from plants that can cause skin irritation at high concentrations.

Based on our research, we recommend using repellents containing the active ingredient DEET if you live in or travel to areas with a high risk of vector-borne disease transmission. However, herbal repellents will work very well to prevent bites from harmful mosquitoes in low-risk areas, as long as you reapply them as needed.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization that brings you trusted facts and analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Immo A. Hansen, New Mexico State University and Hailey A. Luker, New Mexico State University

Learn more:

Immo A. Hansen receives funding from the National Institute of Health.

Hailey A. Luker receives funding from the National Institute of Health.