A key protein called Reelin may help prevent Alzheimer’s disease, according to a growing body of research.

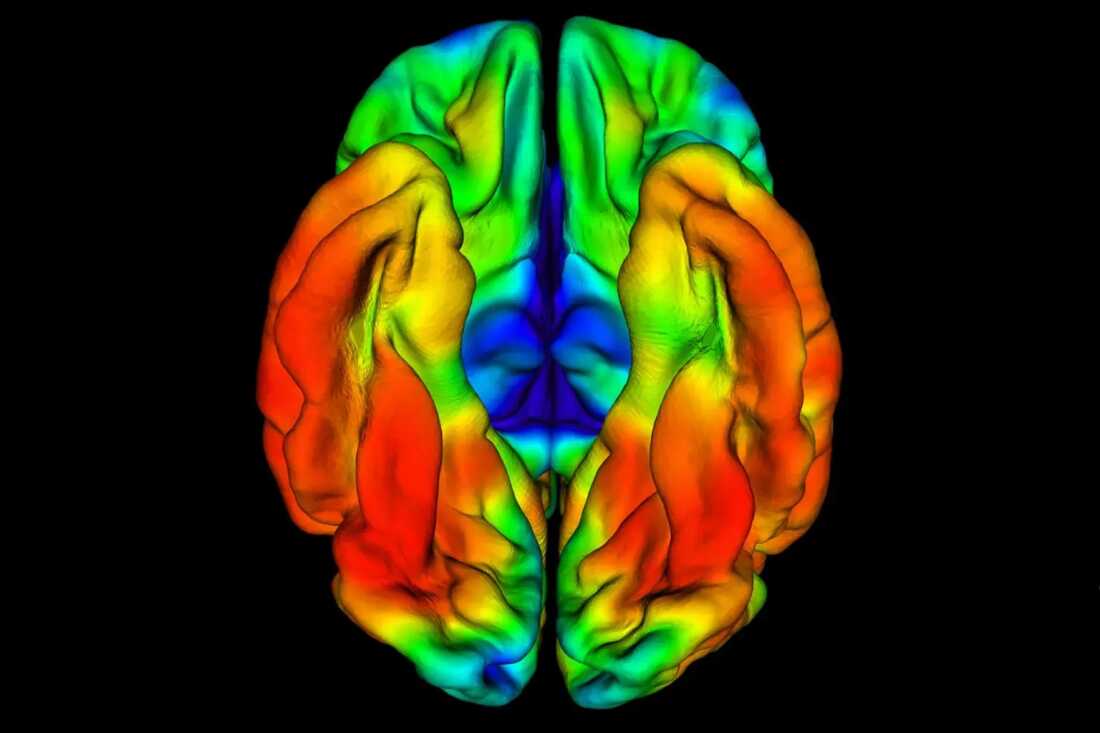

Images GSO/The Image Bank/Getty Images

hide legend

toggle caption

Images GSO/The Image Bank/Getty Images

A key protein that helps assemble the brain early in life also appears to protect the organ from Alzheimer’s and other diseases of aging.

Three studies published last year suggest that the protein Reelin helps maintain thought and memory in diseased brains, although exactly how it does this remains unclear. The studies also show that when Reelin levels drop, neurons become more vulnerable.

“There is growing evidence that Reelin acts as a ‘protective factor’ in the brain,” says Li-Huei Tsai, an MIT professor and director of the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory.

“I think we’re on the right track for Alzheimer’s disease,” Tsai says.

This research has inspired efforts to develop a drug that boosts Reelin, or helps it work better, to prevent cognitive decline.

“It doesn’t take a genius to know that the solution is to take Reelin,” says Dr. Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear. “And now we have the tools to do that.”

From Colombia, a very special brain

Reelin became something of a scientific celebrity in 2023, thanks to a study of a Colombian man who should have developed Alzheimer’s in middle age, but didn’t.

The man, who worked as a mechanic, was part of a large family that carries a very rare genetic variant called Paisa, in reference to the region of Medellin where it was discovered. Family members who inherit this variant are almost certain to develop Alzheimer’s disease in middle age.

This PET image shows the brain of a Colombian man whose memory and thinking remained intact in his late 60s, even though he carried a rare genetic variant that almost always causes Alzheimer’s disease in a 40-year-old.

Yakeel T. Quiroz-Gaviria and Justin Sanchez/Massachusetts General Hospital

hide legend

toggle caption

Yakeel T. Quiroz-Gaviria and Justin Sanchez/Massachusetts General Hospital

“They start to suffer cognitive decline around their 40s and develop full-blown dementia in their late 40s or early 50s,” Arboleda-Velasquez says.

But this man, despite this variant, remained cognitively intact until his late 60s and was not diagnosed with dementia until he was 70.

After his death at the age of 74, an autopsy revealed that the man’s brain was riddled with sticky amyloid plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Scientists also discovered another sign of Alzheimer’s disease: tangled fibers called tau, which can damage neurons. But curiously, these tangles were mostly absent in a region of the brain called the entorhinal cortex, which is involved in memory.

This is important because this region is usually one of the first to be affected by Alzheimer’s disease, Arboleda-Velasquez explains.

Researchers studied the man’s genome and discovered something that could explain why his brain was protected.

He carried a rare variant of the gene that produces the protein Reelin. A study in mice showed that this variant enhances the protein’s ability to reduce tau tangles.

Although the research focused on a single person, it had repercussions throughout the world of brain science and even caught the attention of the then-acting director of the National Institutes of Health, Lawrence Tabak.

“Sometimes the careful study of a single, truly remarkable person can lead to fascinating discoveries with far-reaching implications,” Tabak wrote in his blog post about the discovery.

Reelin Gets Real

After the Colombian man study was published, many researchers “started looking at Reelin,” Tsai says.

Tsai’s team had previously studied the protein’s role in Alzheimer’s disease.

In September 2023, the team published an analysis of the brains of 427 people. They found that people who retained higher cognitive functions as they aged tended to have more neurons producing Reelin.

In July 2024, the group published a study in the journal Nature which provided further support for Reelin’s hypothesis.

The study involved a very detailed analysis of the postmortem brains of 48 people. Twenty-six brains came from people who had symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. The rest came from people who appeared to have normal thinking and memory at the time of their death.

Interestingly, some of these apparently unaffected people had brains full of amyloid plaques.

“We wanted to know, ‘What’s so special about these individuals?'” Tsai says.

So the team conducted a genetic analysis of neurons from six different brain regions. They found several differences, including a surprising one in the entorhinal cortex, the same region that appeared protected from tau tangles in the Colombian men.

“The neurons most vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease neurodegeneration in the entorhinal cortex share a common feature,” Tsai says: “They highly express Reelin.”

In other words, Alzheimer’s disease appears to selectively damage neurons that produce Reelin, the protein needed to protect the brain against the disease. As a result, Reelin levels decline and the brain becomes more vulnerable.

The finding fits with what scientists learned from the experience of a Colombian man whose brain defied Alzheimer’s disease. He carried a variant of the RELN gene that appeared to make the protein more powerful. So that could have compensated for any Reelin deficiency caused by Alzheimer’s.

At the very least, the study “confirms the importance of Reelin,” Arboleda-Velasques says, “which, I have to say, had been overlooked.”

A breakthrough achieved thanks to a Colombian family

Reelin’s story might never have come to light without the cooperation of about 1,500 members of an extended Colombian family who carry the Paisa gene variant.

The first members of this family were identified in the 1980s by Dr. Francisco Lopera Restrepo, director of the Department of Clinical Neurology at the University of Antioquia. Since then, members have participated in numerous studies, including trials of experimental drugs against Alzheimer’s disease.

Along the way, scientists identified a handful of family members who inherited the Paisa gene variant but remained cognitively healthy well beyond the age at which dementia typically sets in.

Some appear to be protected by an extremely rare version of the APOE gene, called the Christchurch variant. Scientists now know that others appear to be protected by the gene that causes Reelin.

Both discoveries were possible because some members of the Colombian family were examined repeatedly in their own country, and even flown to Boston for brain scans and other advanced tests.

“These people agreed to participate in research, to have their blood taken and to donate their brains after they died,” Arboleda-Velasquez says. “And they changed the world.”