NASA has announced the first detection of possible biosignatures in a rock on the surface of Mars. The rock contains the first Martian organic material decisively detected by the Perseverance rover, as well as curious discolored spots that could indicate past activity of microorganisms.

Ken Farley, project scientist on the mission, called the rock “the most puzzling, complex and potentially important rock ever studied by Perseverance.”

Perseverance is part of Mars 2020, the first mission since Viking to be explicitly designed to search for life on Mars (officially, to “search for potential evidence of past life using observations of habitability and preservation as a guide”). It’s safe to say that this goal has now been achieved: potential evidence of past life has been found. But there’s still a lot of work to do to test this interpretation of the data. Here’s what we know.

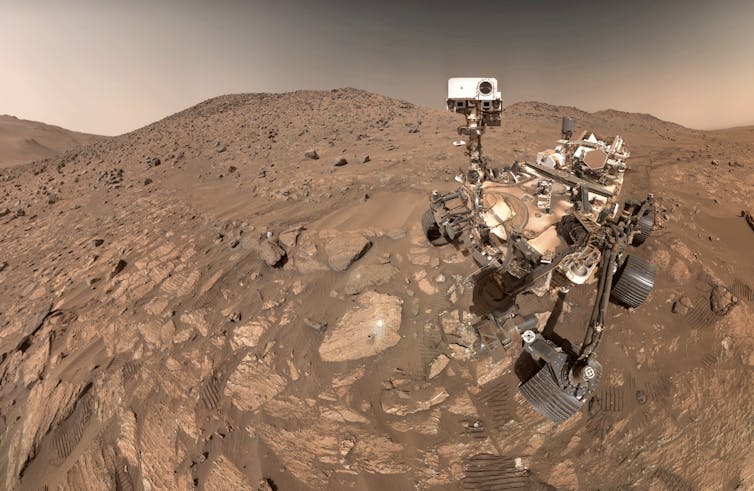

Since landing in Jezero Crater a few years ago, Perseverance has been traversing a series of rocks formed nearly four billion years ago. Back then, Mars was far more habitable than today’s cold, dry, toxic Red Planet.

There were thousands of rivers and lakes, a thick atmosphere, temperatures and chemical conditions conducive to life. Many of Jezero’s rocks are sedimentary: mud, silt and sand washed down by a river flowing into a lake.

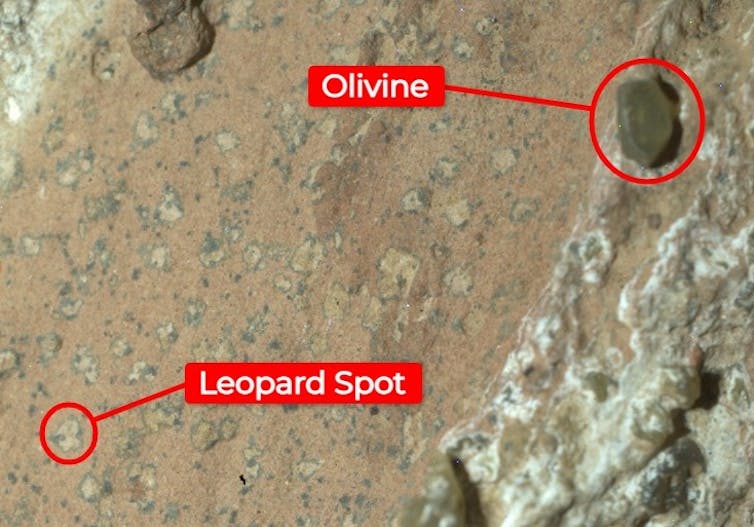

The new discovery concerns one of these rocks. Colloquially called “Cheyava Falls” (a waterfall in Arizona), it is a small reddish block resembling clay, enriched with organic molecules. The rock is also dotted with parallel white veins. Between the veins are whitish spots on the scale of millimeters with dark edges. For an astrobiologist, all these features are intriguing. Let’s examine them one by one.

First, “organic molecules” are made of carbon and hydrogen (usually also sulfur, oxygen, or nitrogen). Examples include proteins, fats, sugars, and nucleic acids from which all life as we know it is built.

Organic matter is abundant in Earth’s rocks, much of it from the remains of ancient organisms. But the term “organic” is slightly misleading: such molecules can also be produced by non-biological reactions (in fact, we know this was happening four billion years ago on Mars).

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Simple, non-biological organic molecules are common in the universe, and NASA’s Curiosity rover has already detected them in clay rocks in Gale Crater. They were also reportedly detected by Perseverance in Jezero Crater last year.

Still, Farley calls the new observation the first “convincing detection” of organic compounds by Perseverance. NASA hasn’t told us what types of organic molecules are actually present in Cheyava Falls, so it’s hard to gauge where they’re coming from. They could be biological, but a full laboratory analysis on Earth would be needed to decide that.

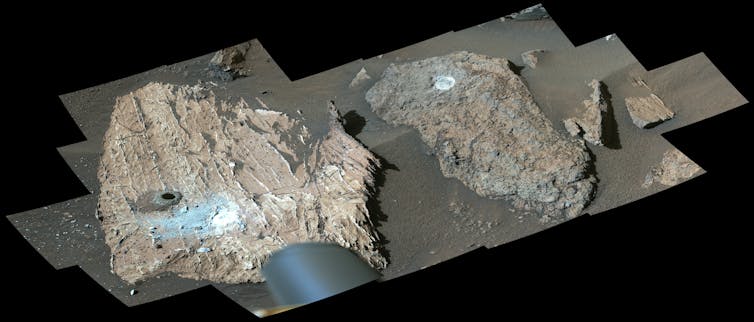

Next, the veins. These are composed of calcium sulfate, which precipitated like limestone when liquid water flowed along fractures in the subsurface. Veins like these are common in Martian sedimentary rocks (Curiosity has seen many), and of course, they are not “biosignatures,” even though they normally represent habitable conditions.

My own work has shown that microorganisms living in underground fractures can produce chemical fossils that become trapped in veins of calcium sulfate. Interestingly, the veins at Cheyava Falls also contain olivine, an igneous mineral. This could suggest that the water was injected at temperatures too high for life. We need more data to know.

Finally, what about those whitish, discolored spots? They look like the “reduction spots,” also called “leopard spots,” commonly seen on Earth’s red sedimentary rocks. These rocks are rusty red because they contain an oxidized form of iron. When chemical reactions change the iron to a less oxidized state, it becomes soluble. Water washes away the pigment, leaving behind a bleached spot.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

On Earth, these reactions are often driven by bacteria living below the surface. They use oxidized iron as an energy source, much as you and I use oxygen from the air. On Mars, bacteria-like organisms could have used organic matter in the rock to complete the reaction (much as we use glucose from the food we eat).

Reduction spots have never been seen before on Mars, although the whitened linear “halos” observed by Curiosity in Gale Crater are somewhat similar. As one of the few astrobiologists to have studied reduction spots on Earth—and found evidence of biological processes within them—I am personally thrilled. But as always, caution is advised.

Potential nonbiological causes need to be explored and eliminated. Iron dissolution reactions can and do occur in lifeless sedimentary rocks. The dark margins of the Cheyava Falls patches are enriched in both iron and phosphate, an association that may have occurred around some calcium sulfate veins on Mars. This observation is consistent with life, but also with chemical reactions driven by acidic fluids.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Still, the new findings will encourage those calling on NASA and the European Space Agency to continue the multibillion-dollar sample-retrieval program that Perseverance was supposed to launch. The rover has now extracted a chunk of rock from Cheyava Falls. If current plans come to fruition — which is a big if — then a future spacecraft will retrieve that chunk (and others) and bring it back to Earth.

The results will then be analyzed in state-of-the-art laboratories that are far more powerful than Perseverance’s instruments. In the meantime, we can’t be certain that Perseverance has actually found fossils of ancient life on Mars. The evidence so far isn’t definitive, but it’s certainly fascinating.