NASA announced Wednesday that it is ending the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) project. This is the second time in less than a decade that NASA has abandoned its planned lunar exploration mission in search of water ice, six years after the cancellation of a similar mission, Resource Prospector.

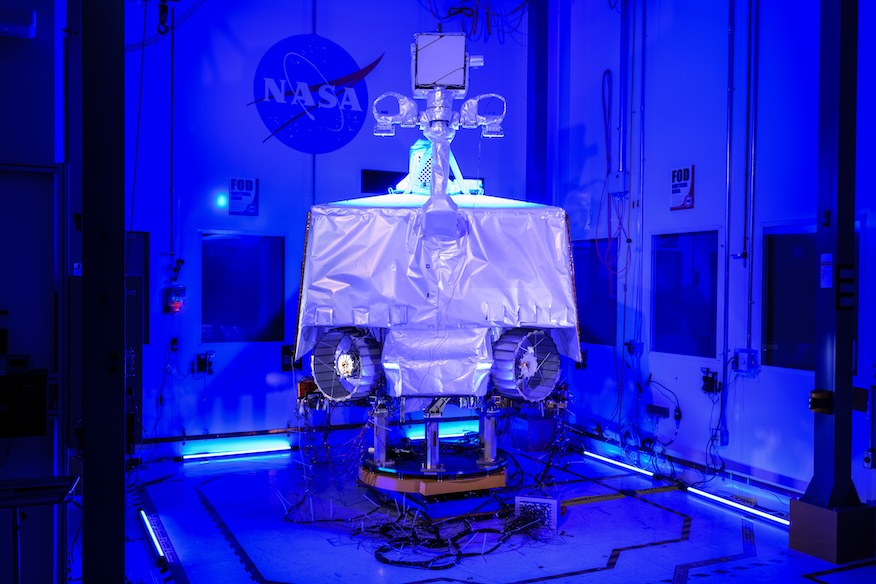

The 948-pound (430-kilogram) rover was designed to fly to the moon’s south pole aboard Astrobotic’s Griffin lander, the Pittsburgh-based company’s second planned lunar mission. Astrobotic’s first mission, the smaller Peregrine lander, ended prematurely in January when a propulsion problem prevented it from reaching the moon.

In a teleconference with members of the press, Joel Kearns, NASA’s associate deputy administrator for exploration in the Science Mission Directorate, pointed to rising costs as a major factor in VIPER’s cancellation.

“When we formalized the VIPER project, we told Congress that the project budget would be $433.5 million and that the landing would occur in late 2023,” Kearns said. “We had already made the decision to reschedule the landing to 2024 so that Astrobotic could conduct additional propulsion testing on the lander.”

“When we made that decision, we updated the VIPER work plan and reset the budget to $505.4 million with a landing in late 2024. But our latest estimate, done earlier this year, showed that because we were no longer planning to land VIPER in late 2024, but had to do it for the 2025 science window, the cost of the VIPER project was estimated at $609.6 million.”

Kearns said exceeding 30% of the original budget was a step too far and automatically triggered what he called a cancellation review, which took place in June. In 2019, when VIPER was first announced, NASA had originally estimated the gold-cart-sized rover at $250 million with a delivery to the moon in 2022.

In a blog post published in May 2024, VIPER project manager Dan Andrews noted that in April, the lander successfully passed a system test readiness review, allowing VIPER to move on to stress and environmental testing.

“These environmental tests are important because they require our rover to experience the conditions it will encounter during launch, landing, and in the thermal environment of operating at the lunar South Pole,” Andrews wrote in May. “Specifically, the acoustic tests will simulate the harsh, vibrating experience of a ‘rock concert’ during launch, while the thermal vacuum tests will expose VIPER to the hottest and coldest temperatures it will encounter during the mission, all while operating in the vacuum of space. It’s a challenging task, but we need to make sure we’re ready for it.”

In his comments Wednesday, Kearns said that at this point, VIPER had not completed system-level environmental testing, and some ground systems needed for the rover to operate on the moon were also not complete.

He said that by canceling VIPER, NASA would save at least $84 million, “which is the cost of continuing to complete the flight and ground systems route and then operate the mission, which now cannot occur in 2024.”

Asked why this decision was made when NASA has seen similar or larger budget increases and has not canceled programs, Kearns said they were not only bound by congressional budget constraints, but also that the estimates cited may not be the end of the story.

“One of our concerns was the immediate cost, which would have to be taken away from another piece of NASA science to prepare for the September 2025 landing, but another concern was that the landing would not happen in September 2025 and if it happened later than November, it would probably happen in 2026, which would probably require a similar amount of money to continue through 2026,” Kearns said.

A notable part of this concern about the schedule came from the fact that Kearns had said the Griffin lander would not be ready until September 2025.

“We also considered that it might be at least possible that the Griffin lander’s availability for launch could be delayed beyond September 2025. The Griffin lander itself would need to be ready for launch by November 2025, or it would miss the VIPER science operations window for this mission by 100 days after landing,” Kearns said. “VIPER can only take its measurements under special conditions at the South Pole, when there is a lot of sunlight available, what we call the South Pole summer, and also a way to communicate directly by radio with Earth.”

“That’s a challenge for any long-duration mission that goes to the South Pole and doesn’t use, for example, nuclear power for heat and electricity,” Kearns added. “You have to be very careful about how long the darkness lasts.”

What happens now?

NASA will maintain its $323 million contract with Astrobotic, which will allow Griffin Mission One to move forward toward a 2025 launch. Kearns said the lander will now travel to the moon with a mass simulator, which will weigh about the same as VIPER.

He added that Astrobotic may seek additional commercial payloads for the lander and, if necessary, the size of the mass simulator could be reduced to compensate.

“NASA has decided, given the magnitude, the schedule and the cost, the fixed price that we agreed to with Astrobotic for the Griffin mission, that we are not going to replace any additional science instruments on Griffin because we believe that if we did, it could cause schedule delays and increased costs to the government,” Kearns said. “So our current focus for Griffin is to get the data from the successful landing and how their propulsion system is working.”

When asked whether VIPER could switch to another NASA-reserved lunar lander, such as the cargo version of Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander, Nicola Fox, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said that could have negative budgetary impacts for other CLPS missions.

“It’s more of a financial risk and a threat to the rest of NASA’s program,” Fox said.

She said NASA had informed congressional officials of its decision and was awaiting their response.

In a post on X, formerly Twitter, Astrobotic said it aims to launch its Griffin lander in the third quarter of 2025. In April, the company announced it would launch its own shoebox-sized rover called CubeRover in partnership with the company Mission Control, as part of Griffin Mission One.

The lander will also carry the LandCam-X payload, designed on behalf of the European Space Agency and French startup Lunar Logistics Services. It is designed to “take photographs as it approaches the Moon to improve the accuracy and safety of future lunar landings.”

Astrobotic has not yet released a full list of its commercial customers.