Geophysicist John Vidale noticed something striking while tracking how seismic waves travel from the Earth’s crust through its core.

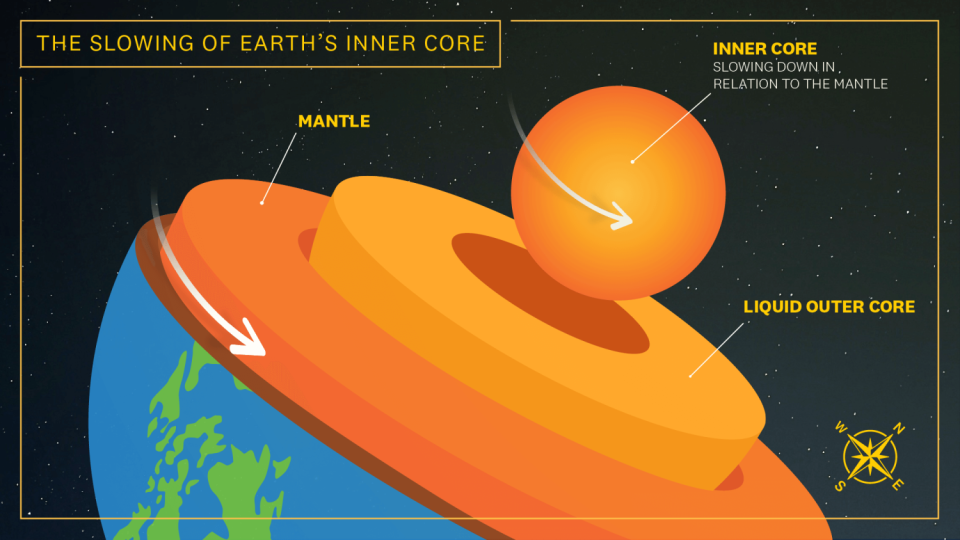

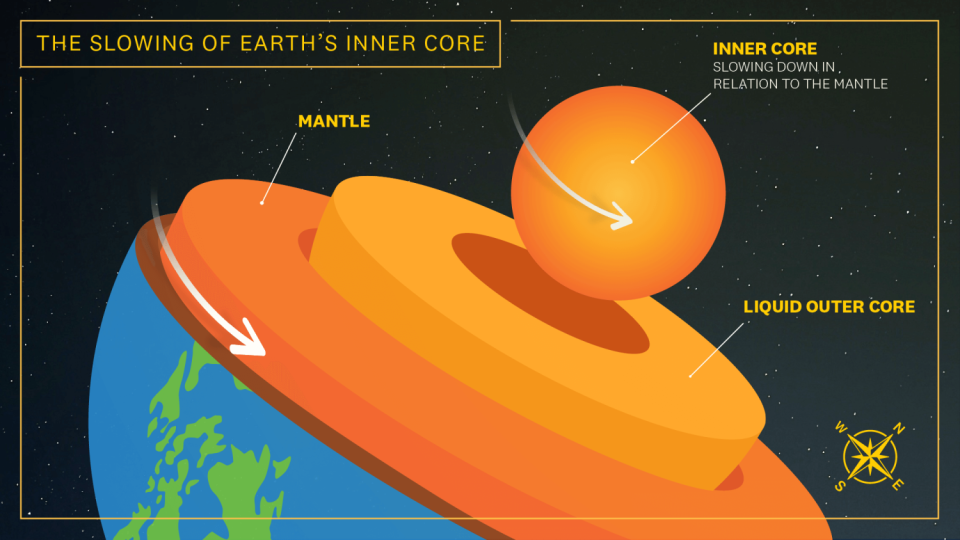

The center of the planet, a solid ball of iron and nickel floating in a sea of molten rock, appears to be slowing down relative to the motion of the Earth itself. The inner core has slowed so much that it has virtually gone into reverse.

The discovery by Vidale and his counterpart Wei Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, published recently in the journal Nature, offers the most compelling evidence yet that the core appears to operate with a mind of its own.

“It could be a round trip on a bike, but it could also be a random walk,” Vidale said. “He went one way for a while and then he came back the other way. Who knows what he’s going to do next?”

Learn more: Joshua Tree’s Famous Rattlesnake Trainer Wants to Change the Way You Think About Reptiles

The fluctuations occurring 3,000 miles below us won’t affect life on the planet’s surface in any noticeable way — at least not yet, Vidale said.

“From what we’ve seen, it has virtually no effect on people,” said Vidale, a professor of Earth sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “It’s part of understanding how the planet evolves. We’d also like to know more about the forces that move the inner core.”

Scientists first had a hunch that the inner core was moving in the 1990s, he said. It took years to back up that theory with concrete evidence, largely because of the difficulty of studying a mass so far out of reach — and suspended in a hellish sea of liquid iron that’s 8,000 to 10,000 degrees.

In contrast, Vidale, who directed USC’s Southern California Earthquake Center from 2017 to 2018, observed the planet by tracking seismic waves from earthquakes off the lower tip of South America. As the waves traveled through the planet’s core, they were recorded on 400 seismometers positioned halfway around the globe, in Alaska and northern Canada. The sensors were the same type used to measure ground vibrations during nuclear tests.

He compared these precise measurements to earthquake signals recorded in previous years to see if they matched up. He determined that the rotation had been slowing since 2010. Before that, the core’s rotation had been speeding up.

These discoveries add to the mystery of the most unfathomable part of our world, Vidale said. Literature and lore about the Earth’s core have filled the knowledge gap with all sorts of fanciful ideas.

“I’m not a great philosopher, but we’ve all had nightmares about what’s happening on Earth,” Vidale said. “Just a few hundred years ago, people thought the planet was hollow and people lived on it. It’s pretty exotic, exotic like Jupiter, but it’s right under our feet.”

In Jules Verne’s 1864 science fiction classic “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” a German professor, his nephew and their guide descend into the planet through a volcano in Iceland – encountering caverns, an underground ocean, living dinosaurs, strange sea creatures and even a prehistoric giant breeding mastodons along the way – and are eventually spat out by a volcano off the coast of Sicily.

The 2003 disaster movie “The Core” imagines that the rotation of the Earth’s center has stopped, damaging the magnetic field that envelops the planet and triggering a violent storm that destroys Rome and “invisible microwaves” that melt the Golden Gate Bridge. A team of top scientists tunnels through the Earth’s layers to blast the core with a nuclear bomb.

In the real world, no human could survive the unimaginable heat and crushing pressure, even if there were a vehicle capable of tunneling to the core, Vidale said.

Learn more: Cloudy with risk of rage: Climatologists outraged over Los Angeles weather station move

It’s true that the outer core generates electrical currents that power the planet’s magnetic field, but Vidale says changes in the Texas-sized inner core are too tiny to have an impact.

Although the planet’s underground reality is less fantastical than novels and Hollywood movies make it out to be, it remains no less fascinating to those like Vidale whose mission is to counter conjecture with fact.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that the inner core is sensitive in different ways to the activity of the layers of the Earth that surround it.

“The mechanism is this: the outer core circulates and creates a magnetic field, which sort of drives the inner core back and forth,” Vidale explained.

Another player in the endless tug-of-war taking place inside the planet is the lower level of the planet’s mantle, whose mix of hard and less dense material carries its own special magnetic pull, Vidale said.

“We kind of think that the outer core is wiggling the inner core, but the mantle is trying to keep it aligned – maybe that’s why it’s wobbling,” he said.

Recent findings about the inner core have sparked heated disagreement among the world’s leading geologists and led to competing theories of varying degrees of credibility, Vidale says. Some don’t believe the core rotates at all. Others insist that forces on the surface, such as earthquakes, briefly alter the rotation.

On the phone, Vidale reads an article by an Australian scientist who greets Vidale’s recent findings with great skepticism. The Australian claims that this analysis will lead to “the erosion of seismology as a credible branch of science and the destruction of seismologists as credible researchers.”

“I think he’s just frustrated, he knows he’s lost,” Vidale said, gently teasing his peer.

“It’s exciting because the core is quite big, it’s moving in measurable ways, and it’s a mystery,” Vidale said. “We’re making progress and seeing more things, talking to people around the world and trying to get more data… What our paper has done is it’s convinced most from the community.”

This article was originally published in the Los Angeles Times.