Just being around blue spaces (the sea, rivers and lakes) can help us feel more relaxed, as water triggers our parasympathetic nervous system, helping our bodies rest and digest.

This calming effect, which slows our heart rate and lowers blood pressure, explains why so many people find joy and comfort in water-related activities.

But enjoying the water also comes with serious risks that cannot be ignored. In the UK, drowning is one of the leading causes of accidental death, surpassing even house fires and cycling accidents. Every year, around 400 people accidentally drown in coastal and inland waters in the UK.

It is worth noting that 40% of these incidents occur when people have not even planned to be in the water, for example when they are surprised by the rising tide while walking along the coast or when they jump in to save a dog. This is a stark reminder that traditional water users are not the only ones at risk.

According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, more than 100,000 sea rescues are carried out each year. These rescues are tragedies that leave lasting scars, with survivors (and their families) often suffering serious injuries or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data from incident reports tell us that globally, men are 80% more likely to drown than women, particularly middle-aged and adolescent men.

This higher risk is attributed to the fact that men spend more time in the water and engage in riskier behaviors such as swimming alone, at night, drinking alcohol and neglecting life jackets.

Social pressures and the tendency to underestimate risks (assuming that water seems safe when it is not) also contribute to higher drowning rates among men.

My team of neuroscience and communication academics at Bournemouth University are working with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution to research how to improve water safety communications by using virtual reality simulations to record brain activity during immersion in water.

Using emotional sensors in smart glasses, we discover how emotional charges, such as fear, are experienced during virtual reality scenarios, such as an unexpected fall into water from a boat or a cliff.

We will be showcasing this technology at an exhibition at Bournemouth University in August 2024 to highlight the risks of being near water and to collect more data.

So far, our research has highlighted the challenges and complexities of human emotions in making safer decisions in the water and the role that instinct plays in gender decision-making.

Men appear to have a different perception of risk and a tendency toward impulsive decision-making, while women tend to be more cautious and have a greater propensity for safety and risk avoidance.

Water activities also have an impact on risks. People tend to prepare for activities like paddleboarding and kayaking with the right equipment and skills. This means they are generally safer than playing in the water on inflatable toys such as air mattresses, which are often used without preparation and are also easily swept away by a strong current.

An unexpected entry into the water, such as being caught by the tides while walking along the shore or taking a selfie at the edge of a cliff, is even more dangerous because of the element of surprise and lack of preparation when falling into the water.

This lack of preparation greatly increases the risk of drowning, as well as the fact that some people who unexpectedly fall into the water are usually fully clothed and may also be afraid of water.

Drowning deaths often occur on inland waterways because these canals, streams, lochs and lakes are much colder than the sea, surprisingly calm and lurk with many dangers.

For example, the water may be unexpectedly deep, there may be hidden currents or debris such as broken glass or an old bicycle. The water may be polluted and pose a serious health threat or it may simply be difficult to get out of due to steep and slippery banks.

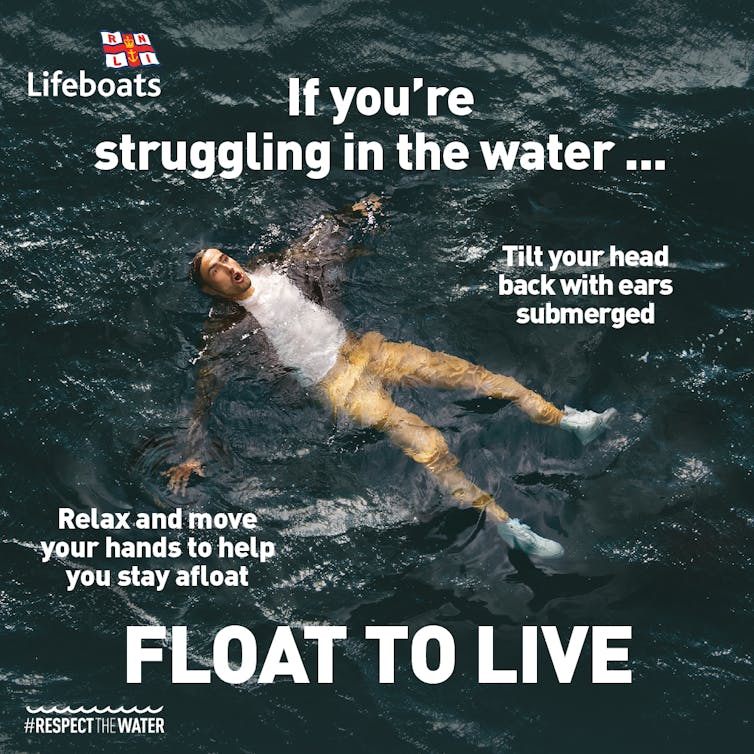

Float to live

Instinct plays a crucial role in how we react to water. We can be relaxed and swimming for a minute, then water conditions change quickly and a rip current can catch you off guard.

Our instinct is often to swim against the current, but the best thing to do is to swim parallel to the shore to escape the current. People who are inexperienced and uninformed about rip currents probably won’t know how to spot them, let alone how to safely navigate them.

When we suddenly enter cold water, our body automatically reacts to increase our alertness and adrenaline levels due to the shock of the cold water. This makes us gasp, hold our breath, and try to swim hard until we are exhausted. Overcoming this instinct could save your life.

Whether you’re planning a refreshing swim, a leisurely stroll along the shoreline or a run along a canal, knowing how to stay safe is essential. This knowledge can mean the difference between a safe outing and a tragic accident.

Research shows that following these five simple steps is very effective. They are easy to remember and can be followed by anyone, regardless of swimming ability or whether you are in fresh or salt water.

First, hold your head back with your ears submerged to keep your airway open. Resist the urge to panic, try to relax and breathe normally. Move your hands gently as you paddle, as this will help you stay afloat. Don’t worry if your legs sink, everyone’s buoyancy is different. Finally, spread your arms and legs, as this really helps to maintain your stability in the water.

And if you spot someone in distress, don’t jump in to save them: instead, shout the “float to live” steps and immediately call your local emergency line to request the Coast Guard.![]()

Jill NashLecturer at Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.