Tycho Brahe, Danish Renaissance astronomer and alchemist. Credit: wikipedia

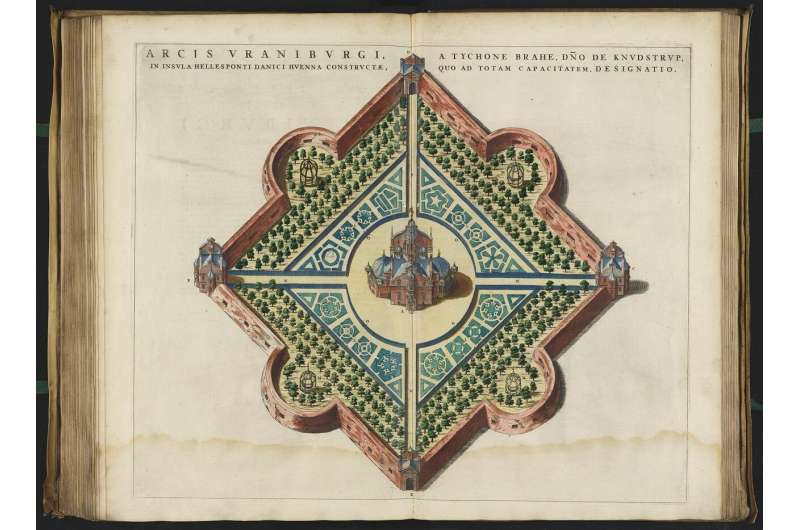

In the Middle Ages, alchemists were known for their secrecy and did not share their knowledge with others. The Danish Tycho Brahe was no exception. Therefore, we do not know precisely what he did in the alchemical laboratory located below his combined residence and observatory, Uraniborg, on the Swedish island of Ven.

Only a few of his alchemical recipes have survived and very little remains of his laboratory today. Uraniborg was demolished after his death in 1601 and the building materials were scattered for reuse.

However, during an excavation between 1988 and 1990, shards of pottery and glass were discovered in the former Uraniborg garden. It is believed that these shards came from the alchemical laboratory in the basement. Five of these shards, four glass and one ceramic, were chemically analyzed to determine what elements the original glass and ceramic vessels came into contact with.

The chemical analyses were carried out by Professor Emeritus and archaeometry expert Kaare Lund Rasmussen from the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy at the University of Southern Denmark. Poul Grinder-Hansen, senior researcher and museum curator at the National Museum of Denmark, supervised the historical contextualisation of the analyses.

Enriched levels of trace elements were detected in four of them, while one glass shard showed no specific enrichment. The study was published in the journal Heritage sciences.

“What is most intriguing are the elements found in higher concentrations than expected, indicating enrichment and providing insight into the substances used in Tycho Brahe’s alchemical laboratory,” Lund Rasmussen said.

The enriched elements are nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury and lead, and they were found inside or outside the flakes.

The Uraniborg building on the island of Ven (now in Sweden) was an observatory, laboratory and residence for the Danish Renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe. Credit: wikipedia

Most of these discoveries are not surprising for an alchemist’s laboratory. Gold and mercury were, at least in the upper classes of society, substances known and used against a wide range of diseases.

“But tungsten is a very mysterious metal. It hadn’t even been described at the time, so what can we deduce from its presence on a shard from Tycho Brahe’s alchemy workshop?” asks Lund Rasmussen.

Tungsten was first described and produced in pure form over 180 years later by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Tungsten occurs naturally in some minerals, and it is possible that the element came to Tycho Brahe’s laboratory via one of these minerals. In the laboratory, the mineral may have undergone processing that separated the tungsten, without Tycho Brahe realizing it.

There is, however, another possibility which, according to Professor Lund Rasmussen, is not based on any evidence, but which could be plausible.

Already in the first half of the 16th century, the German mineralogist Georgius Agricola had described something strange in the tin ore of Saxony, which caused him problems when he tried to smelt the tin. Agricola called this strange substance contained in the tin ore “wolfram” (wolf foam in German, later renamed tungsten in English).

“Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and therefore knew about the existence of tungsten. But this is not something we know or can say for sure based on the analyses I have done. This is just a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples,” Lund Rasmussen said.

Tycho Brahe belonged to the branch of alchemists who, inspired by the German physician Paracelsus, attempted to develop medicines for various diseases of the time: plague, syphilis, leprosy, fever, stomach ailments, etc. But he moved away from the branch that attempted to create gold from less precious minerals and metals.

Tycho Brahe receives Jacob VI of Scotland at Uraniborg. Credit: Royal Danish Library

Like other medical alchemists of the time, he kept his recipes secret and shared them only with a select few, such as his patron, Emperor Rudolf II, who is said to have received Tycho Brahe’s prescriptions for plague medicine.

We know that Tycho Brahe’s plague medicine was complicated to produce. It contained theriac, one of the standard remedies of the time for almost everything, and could contain up to 60 ingredients, including snake flesh and opium. It also contained copper or iron sulfate, various oils and herbs.

After various filtrations and distillations, the first of Brahe’s three recipes against the plague was obtained. It could be made even more effective by adding tinctures of coral, sapphires, hyacinths or potable gold, for example.

“It may seem strange that Tycho Brahe was involved in both astronomy and alchemy, but when you understand his worldview, it makes perfect sense. He believed that there were clear connections between celestial bodies, terrestrial substances and the organs of the body,” Grinder-Hansen explains.

“Thus the sun, gold and the heart were related, and the same applied to the moon, silver and the brain; Jupiter, tin and the liver; Venus, copper and the kidneys; Saturn, lead and the spleen; Mars, iron and the gallbladder; and Mercury, mercury and the lungs. Minerals and precious stones could also be related to this system, thus emeralds, for example, belonged to Mercury.”

Lund Rasmussen had already analyzed Tycho Brahe’s hair and bones and discovered, among other things, gold. This could indicate that Tycho Brahe himself had taken medicines containing potable gold.

More information:

Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Chemical analysis of glass and ceramic fragments from Tycho Brahe’s laboratory in Uraniborg on the island of Ven (Sweden), Heritage sciences (2024). dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

Provided by the University of Southern Denmark

Quote: Chemical Analyses Reveal Hidden Elements in Renaissance Astronomer Tycho Brahe’s Alchemy Lab (2024, July 24) retrieved July 26, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-chemical-analyses-hidden-elements-renaissance.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.