The desert regions of North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula have been extensively studied by archaeologists as home to early humans and as migration routes along “green corridors.”

The archaeology of the desert belt of the west coast of southern Africa has not received the same attention.

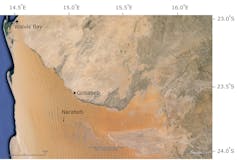

The Namib Sand Sea, part of the Namib Desert, lies on the west coast of Namibia. It is a hyper-arid landscape of towering dunes, occupying about 34,000 km² between the towns of Lüderitz in the south and Walvis Bay in the north. However, there are indications that this environment was not always so dry and inhospitable, suggesting that there is still much to learn about ancient human life here.

Google, Landsat/Copernicus Image

We are part of an interdisciplinary research team of physical geographers, archaeologists and geospatial scientists, interested in the long-term history of deserts and human-environment interactions.

Our research provides a timeline of the presence of a small freshwater lake that once existed in the Namib Sand Sea. This lake was fed by an ancient river and is surrounded by a rich assemblage of stone tools dating from the African Middle Stone Age (made between about 300,000 and 20,000 years ago), indicating that humans ventured into this landscape and used this occasional water source.

The dating of the ancient lake site of Narabeb provides insight into when ancient humans might have lived here. It draws attention to the Namib Sand Sea as a place that archaeologists should study to learn more about the deep and far-reaching human connections that exist across southern Africa.

An ancient lake and shifting sand dunes

Today, Narabeb is a landscape dominated by long sand dunes that rise more than 100 meters above the former lake site. There is no standing water here and the landscape receives little or no rain in most years. However, this is probably not what our ancestors would have seen here. Away from the lake, they might have seen a relatively flat plain, seasonally covered by grasses, next to a river.

The clue lies in the sediments of the site: layers of mud deposited by water. To know when Lake Narabeb existed, it was necessary to date these layers.

Kaarina Efraim (collaborator)

We used a technique called luminescence dating, which involves making sand glow to tell the time. The sand grains release a trapped signal that builds up when the sand is buried underground and resets when the sand is exposed to sunlight. Using this technique, we can date when different layers were on the surface before they were buried. We dated the sand below and above the mud layers deposited by the water. Our results show that the lake was present at Narabeb at some point between 231,000 ± 20,000 and 223,000 ± 19,000 years ago, and again around 135,000 ± 11,000 years ago.

Another clue is the shape of the landscape east of Narabeb. It is devoid of dunes, reminding us that ancient humans were not the only ones migrating into the Namib sand sea. Are the dunes moving? For how long? And how fast?

Google, Corpernicus

It is logistically impossible to drill into the center of these dunes. Instead, we used a new mathematical model.

Modelling suggests that it would have taken about 210,000 years to accumulate the amount of sand around Narabeb (these 110m high dunes). This figure is remarkably close to the oldest age of the lake. It suggests that the dunes were perhaps just beginning to form and that a river was feeding the lake with fresh water, feeding animals and attracting people. The sediments at Narabeb also clearly tell us that a river once flowed where the dunes are today.

The winds pushed the dunes from the south and west to the north and east, creating barriers to the river and hindering the movement of people and animals along the watercourse.

Ancient human presence

At other sites in the Namib we have found Early Stone Age tools belonging to an earlier species of Homo genre. It is part of a growing body of evidence, adding to research in the Kalahari Desert in central southern Africa, that suggests that southern African desert landscapes are more important to the history of human evolution and technological innovation than previously thought.

The objects found at Narabeb fit into the tradition of Middle Stone Age stone tools. Narabeb is a particularly rich site for stone tools, suggesting that people made tools here for a long time and may have visited the site for several generations.

George Leader (contributor)

This research illustrates the need for in-depth study of unmapped areas along major human and animal migration routes. These areas could reveal exciting evidence of cultural diffusion, innovation, and adaptation to marginal and changing environments.

Our results also make us think about the dynamic nature of environmental conditions in one of the oldest desert regions on Earth. It was long thought that the Namib was consistently very dry for about 10 million years, and that it was not a place capable of containing “green corridors” at the periods of interest to archaeologists. We can now challenge this idea.

Future steps

Recent funding from the Leverhulme Trust will allow us to extend our fieldwork, document archaeological sites and date these ‘green corridors’ across more of this landscape. An initial 160km walking survey along the ancient watercourse has revealed a vast landscape littered with artefacts. We also need to know more about where ancient people found the materials they used to make stone tools.

This will allow us to reconstruct a network of archaeological sites and show where human migrations could have been possible in this part of southern Africa. Until now, this was a gap in the archaeological map.

Read more: Ancient pots reveal clues to how diverse diets helped pastoralists thrive in southern Africa

Further research is also needed to understand the climate changes that have allowed the rivers to flow into the Namib. This desert on the west coast of the southern hemisphere has a very different setting to North Africa and Arabia, which have a good basis for understanding their periodic “green corridors.” Ongoing work with the wider scientific community, including climate modellers, could provide a clearer picture of the Namib’s “green corridors.”