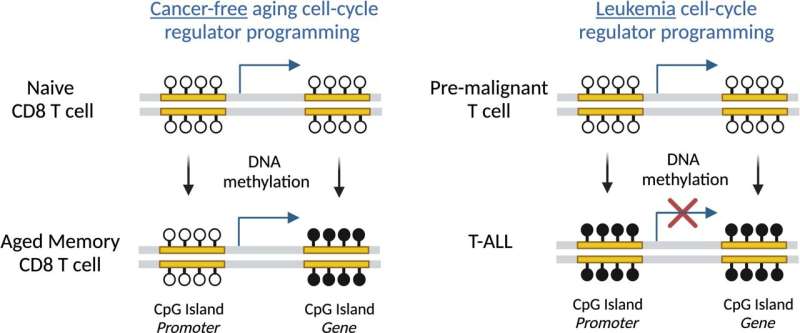

Cartoon summary of experimental age-associated DNA methylation programs that delineate longevity versus malignancy among T cells. Credit: Natural aging (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43587-024-00649-5

While most cell types experience functional decline after years of proliferation and replication, T cells can proliferate seemingly indefinitely and without harm.

Scientists from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the University of Minnesota have studied the unique “epigenetic clock” of T cell aging, demonstrating that T cells can survive an organism for at least four lifetimes. Additionally, the researchers showed that the age of healthy T cells was not related to the chronological age of the body.

Additionally, they determined that malignant T cells from pediatric patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) appeared to have aged up to 200 years. The results were published in Natural aging.

As researchers explore the process of cellular aging through repeated replicative growth cycles, particular patterns have emerged regarding T cells.

“The immune system, by nature, must mount a rapid proliferative response to a pathogen or tumor,” said co-corresponding author Ben Youngblood, Ph.D., Department of Immunology at St. Jude. “And in some contexts, such as in the case of endemic pathogens or chronic viral infections, this happens over and over again. These T cells undergo high proliferation over the course of a human being’s life.”

This raises the question of why, despite these accelerated proliferation rates, this immune response does not trigger cancer development.

The answer lies in the unique ability of T cells to defy aging.

Epigenetic markers offer more precise measurements of age

To study this phenomenon, researchers used specific biomarkers called epigenetic markers that accumulate over time. Like counting the rings on a tree stump in a forest, this “epigenetic clock” tells a retrospective story about the life cycle of a cell, independent of the organism itself. The accumulation of genetic mutations, shortening of telomeres (the protective caps of chromosomes), and methylation patterns are currently considered the most accurate ways to interrogate the aging process.

The researchers saw this as an ideal way to study the curious case of T-cell aging. “We began to ask questions about the hallmarks of aging, particularly epigenetic hallmarks, and how these can be applied to long-lived T cells,” he said. “One of the big questions we had was whether or not these epigenetic clocks are linked to the lifespan of the organism.”

Model shows T cells can survive their organism of origin

Through a collaboration with co-corresponding author David Masopust, Ph.D., University of Minnesota, the researchers found the perfect model to answer their questions. This model used the same T cell line throughout multiple mouse life cycles.

“Dr. Masopust started this model assuming that the cells would eventually decline, but that’s not the case, they just kept going,” says Youngblood. “This led to his seminal 10-year mouse study, which we then used to determine whether limits on organismal lifespans constrain epigenetic clocks.”

Using this model and an epigenetic clock developed for T cells, the researchers explored the DNA methylation patterns of the T cell lineage. They found that age is only a number and that death is not the end.

“Humans don’t live forever. But in this case, we could test this concept for T cells,” Youngblood said. “Is there an end to an epigenetic clock? Does it stabilize? And it didn’t last until four lifetimes, it just kept counting, which was incredible. These cells are not limited by the reasonable limits of the organism’s lifespan.”

Cancer T cells appear hundreds of years old

Next, the researchers determined what happened under conditions of rapid and prolonged proliferation, such as in cancer. The team interrogated T cells from patients with pediatric T-ALL to study what happens to their epigenetic clock.

“If epigenetic clocks were linked to the chronological age of the host, then one would expect T cells from pediatric T-ALL patients to appear young,” said co-corresponding author Caitlin Zebley, MD. , Ph.D., St. Jude. Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. “But our clock predicted that these cells were very old.”

From an experiential perspective, T cells from T-ALL patients appeared to be between 100 and 200 years old. “We think this has to do with the fact that they proliferate so quickly,” Zebley concluded. The T-ALL model has offered valuable insights into the aging process of leukemia cells.

“We were able to use this as a model to subtract all the other leukemia programs to identify those that are associated with normal aging and proliferation versus those that are distinct from leukemia,” Youngblood said. “We have gained greater insight into which epigenetic programs are associated with leukemia and which are simply normal hyperproliferation and aging.”

T cell survival is vital for our survival

Given the activity of our immune system, T cell survival is vital to our overall survival. “T cells have so much opportunity to become cancerous,” Youngblood said, “But they can’t, otherwise humanity wouldn’t exist.”

Youngblood, Zebley and Masopust continue to study the checks and balances that prevent T cells from undergoing malignant transformation. Thanks to this work, potential therapies that would halt, or even reverse, age-related impairments can begin to be considered.

More information:

Tian Mi et al, Conserved epigenetic features of T cell aging during immunity and malignancy, Natural aging (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s43587-024-00649-5

Provided by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

Quote: Age is just a number: the “epigenetic clock” of immune cells works independently of the body’s lifespan (June 12, 2024) retrieved June 13, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com /news/2024-06-age-immune-cell-epigenetic -clock.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.