“It is surely the most solitary organism in the world,” wrote paleontologist Richard Fortey in his book on the evolution of life.

He was talking about Encephalartos woodii (E. woodii), a plant native to South Africa. E. woodii is a member of the cycad family, heavy plants with thick trunks and large, stiff leaves that form a majestic crown. These resilient survivors have survived dinosaurs and multiple mass extinctions. Once widespread, they are now one of the most endangered species on the planet.

The only known savage E. Woodii was discovered in 1895 by botanist John Medley Wood while on a botanical expedition to the Ngoye Forest in South Africa. He looked for others in the surrounding area, but none was found. Over the next two decades, botanists removed the stems and branches and cultivated them in gardens.

Fearing that the last stem would be destroyed, the Forestry Department removed it from the wild in 1916 to keep it in a protective enclosure in Pretoria, South Africa, effectively rendering it extinct in the wild. Since then, the plant has spread throughout the world. However, the E. woodii faces an existential crisis. All plants are clones of the Ngoye specimen. They are all males and without females, natural reproduction is impossible. E. woodii The story is both a story of survival and loneliness.

My team’s research was inspired by the solitary plant dilemma and the possibility that a female might still be out there. Our research involves the use of remote sensing technologies and artificial intelligence to assist us in our search for a female in the Ngoye Forest.

The evolutionary journey of cycads

Cycads are the oldest plant groups still alive today and are often called “living fossils” or “dinosaur plants” because of their evolutionary history dating back to the Carboniferous period, approximately 300 million years ago. During the Mesozoic Era (250 to 66 million years ago), also known as the Age of Cycads, these plants were ubiquitous and thrived in the warm, humid climates that characterized this period.

Although they look like ferns or palms, cycads are neither related. Cycads are gymnosperms, a group that includes conifers and ginkgo trees. Unlike flowering plants (angiosperms), cycads reproduce using cones. It is impossible to tell the male from the female until they reach maturity and produce their magnificent cones.

Female cones are usually wide and round, while male cones appear elongated and narrower. Male cones produce pollen which is carried by insects (weevils) to female cones. This ancient method of reproduction has remained virtually unchanged for millions of years.

Despite their longevity, cycads are today ranked among the most endangered living organisms on Earth, with the majority of species considered threatened with extinction. This is due to their slow growth and reproductive cycles, which typically take ten to twenty years to mature, as well as habitat loss due to deforestation, grazing, and overexploitation. Cycads have become symbols of botanical rarity.

Their striking appearance and ancient lineage make them popular in exotic ornamental horticulture, which has led to illegal trade. Rare cycads can fetch sky-high prices from $620 (£495) per cm, with some specimens selling for millions of pounds each. Poaching of cycads poses a threat to their survival.

Among the most valuable species we find E. woodii. It is protected in botanical gardens by security measures such as alarmed cages designed to deter poachers.

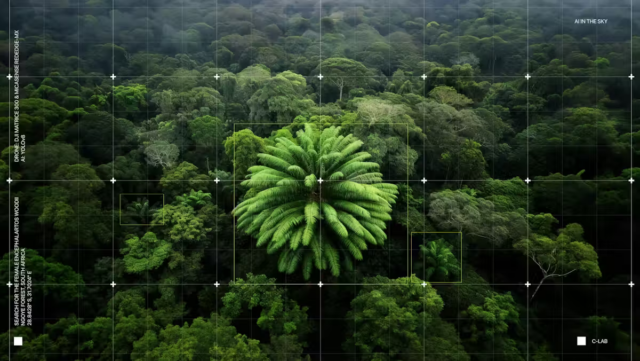

AI in the sky

In our search for a wife E.woodii we used innovative technologies to explore forest areas from a vertical perspective. In 2022 and 2024, our drone surveys covered an area of 195 acres or 148 football fields, creating detailed maps from thousands of drone photos. This is still a small part of the Ngoye forest, which covers 10,000 acres.

Our AI system has improved the efficiency and accuracy of these searches. As E. woodii is considered extinct in the wild, synthetic images were used in training the AI model to improve its ability, via an image recognition algorithm, to recognize cycads by shape in different ecological contexts.

Plant species are disappearing at an alarming rate around the world. Since all existing E. woodii The specimens are clones, their potential for genetic diversity in the face of environmental changes and disease is limited.

Notable examples include the Great Famine in Ireland in the 1840s, where the uniformity of cloned potatoes worsened the crisis, and the vulnerability of clonal Cavendish bananas to Panama disease, which threatened their production as it did for the Gros Michel banana in the 1950s.

Finding a female would mean E. woodii is no longer on the verge of extinction and could revive the species. A female would enable sexual reproduction, provide genetic diversity and represent a breakthrough in conservation efforts.

E. woodii is a sobering reminder of the fragility of life on Earth. But our quest to discover a female E. woodii shows that there is hope for even the most endangered species if we act quickly enough.![]()

Laura Cinti, researcher in bio-art and plant behavior, University of Southampton. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ars_iframe img style=”border: none !important; box-shadow: none !important; margin: 0 !important; max-height: 1px !important; max-width: 1px !important; min-height: 1px !important; min -width: 1px !important; opacity: 0 !important; outline: none !important padding: 0 !important;” src=”https://yatooblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Seeking-a-female-partner-for-the-worlds-loneliest-factory.gif”; alt=”The conversation” width=”1″ height=”1″)(/ars_iframe)