The human body today has many replaceable parts, from artificial hearts to myoelectric feet. What makes this possible is not just complex technology and delicate surgical procedures.

It’s also an idea: humans can and do modify patients’ bodies in extremely difficult and invasive ways.

Where did this idea come from?

Researchers often describe the American Civil War as a turning point in amputation techniques and the design of artificial limbs. Amputations were the most common operation of the war, and an entire prosthetics industry developed in response. Anyone who has seen a movie or television show about the Civil War has probably seen at least one scene of a surgeon gloomily approaching a wounded soldier with a saw in his hand. Surgeons performed 60,000 amputations during the war, spending just three minutes per limb.

Yet a momentous shift in practices related to limb loss began much earlier – in 16th and 17th century Europe.

(Surgical instruments and anatomical icons/Ambroise Paré via Wellcome Collection)

As a historian of modern medicine, I explore how Western attitudes toward surgical and artisanal interventions on the body began to transform around 500 years ago. Europeans went from being reluctant to perform amputations and few options for prosthetic limbs in 1500 to multiple methods of amputation and complex iron fists for the wealthy by 1700.

Amputation was considered a last resort due to the high risk of death. But some Europeans began to believe that they could use it with artificial limbs to shape their bodies.

This break with a millennia-old tradition of non-invasive healing still influences modern biomedicine by giving doctors the idea that crossing the physical limits of the patient’s body to radically modify it and integrate technology could be a good thing. A modern hip replacement would be unthinkable without this underlying assumption.

Surgeons, gunpowder and the printing press

Early modern surgeons passionately debated where and how to cut the body to remove fingers, toes, arms, and legs, in ways that medieval surgeons had not done. This was partly because they were faced with two new Renaissance developments: the spread of the Gunpowder War and the printing press.

Surgery was a profession that was learned through apprenticeship and years of travel to train under different masters. Topical ointments and minor procedures such as repairing fractures, boils, and suturing wounds filled surgeons’ daily practice. Due to their dangerous nature, major operations such as amputations or trepanations – drilling a hole in the skull – were rare.

The widespread use of firearms and artillery strained traditional surgical practices by tearing bodies apart in ways that required immediate amputation. These weapons also created wounds susceptible to infection and gangrene by crushing tissue, disrupting blood circulation, and introducing debris—ranging from wood splinters and metal fragments to remnants of clothing—deep into the body. Mutilated and gangrenous limbs forced surgeons to choose between performing invasive surgeries or letting their patients die.

Printing gave surgeons dealing with these injuries a way to spread their ideas and techniques beyond the battlefield. The procedures they described in their treatises may seem gruesome, not least because they were carried out without anesthesia, antibiotics, transfusions or standardized sterilization techniques.

(Johannes Scultetus/Heidelberg University Library)

But each method had an underlying rationale. Hitting a hand with a mallet and chisel hastened the amputation. Cutting away the dead, desensitized flesh and burning the remaining dead matter with a cauterizing iron prevented patients from bleeding to death.

While some wanted to preserve as much of the healthy body as possible, others insisted that it was more important to reshape the limbs so that patients could use prosthetics.

Never before had European surgeons advocated amputation methods based on the installation and use of artificial limbs. Those who did came to view the body not as something the surgeon simply had to preserve, but rather as something the surgeon could shape.

Amputees, artisans and artificial limbs

While surgeons explored surgical intervention using saws, amputees experimented with making artificial limbs. Wooden dowel devices, as they had been for centuries, remained common lower limb prostheses. But creative collaborations with artisans were the driving force behind a new prosthetic technology that began to appear in the late 15th century: the mechanical iron hand.

Written sources reveal little about the experiences of most limb amputation survivors. Survival rates may have been as low as 25 percent. But among those who managed to get by, the artifacts show that improvisation was key to how they navigated their environment.

This reflected a world in which prosthetics were not yet “medical.” In the United States, a medical prescription is now necessary for any artificial limb. Early modern surgeons sometimes provided small devices like artificial noses, but they did not design, make, or fit prosthetic limbs.

Additionally, there were no professions comparable to today’s prosthetists or medical professionals who make and fit prosthetics. Instead, early modern amputees used their own resources and ingenuity to make one.

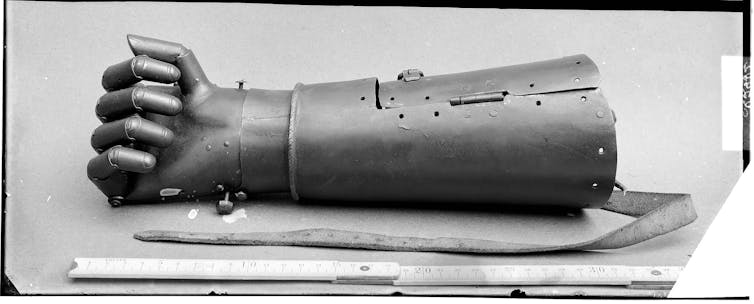

The Iron Hands were improvised creations. Their movable fingers locked in different positions using internal spring-loaded mechanisms. They had realistic details: etched nails, wrinkles, and even flesh-colored paint.

Wearers operated them by pressing down on the fingers to lock them in position and activating a trigger at the wrist to release them. In some iron hands, the fingers move together, while in others they move individually. The most sophisticated ones are flexible in every joint of every finger.

The complex movements were intended more to impress observers than for everyday practicalities. The Iron Hands were the precursor to the Renaissance of the “bionic arms race” of today’s prosthetics industry. Flashier, high-tech artificial hands – then and now – are also less affordable and less user-friendly.

This technology draws inspiration from surprising places, including locks, clocks, and luxury handguns. In a world without today’s standardized designs, early modern amputees ordered prosthetics from scratch by venturing into the artisanal market.

As a 16th-century contract between an amputee and a Geneva watchmaker attests, buyers went to artisans who had never made a prosthesis to see what they could concoct.

Because these materials were often expensive, the wearers tended to be wealthy. In fact, the introduction of iron hands marks the first period when European researchers could easily distinguish people of different social classes based on their prosthetics.

Powerful ideas

The Iron Hands were important bearers of ideas. They prompted surgeons to think about prosthetic placement when operating and created optimism about what humans could achieve with artificial limbs.

But researchers have failed to understand how and why iron hands had this impact on medical culture, because they have been too obsessed with just one type of wielder: knights. Traditional assumptions that wounded knights used iron hands to hold the reins of their horses offer only a narrow view of surviving artifacts.

A famous example colors this interpretation: the “trotter” of the 16th century German knight Götz von Berlichingen.

In 1773, the playwright Goethe loosely based on Götz’s life for a drama about a charismatic and intrepid knight who dies tragically, wounded and imprisoned, exclaiming “Liberty – freedom!” “. (The historical Götz died of old age.)

(State Archives of Baden-Württemberg/Wikimedia Commons., CC BY)

Since then, Götz’s story has inspired visions of a bionic warrior. Whether in the 18th or 21st centuries, we find mythical depictions of Götz standing in the face of authority and holding a sword in his iron fist – an impractical feat for his historical prosthesis. Until recently, scholars believed that all iron hands must belong to knights like Götz.

But my research reveals that many Iron Hands show no signs of being warriors, or perhaps even men. Cultural pioneers, many of whom are known only by the artifacts they left behind, were inspired by elegant trends that valued clever mechanical devices, like the miniature mechanical galleon on display today at the British museum.

In a society that coveted ingenious objects blurring the lines between art and nature, amputees used iron fists to defy negative stereotypes depicting them as pitiful. Surgeons took note of these devices and praised them in their treatises. The iron hands spoke a material language that contemporaries understood.

Before the modern body made up of replaceable parts could exist, the body had to be reinvented into something that humans could model. But this reinvention required the efforts of more than just surgeons. It also required the collaboration of amputees and craftsmen who helped build their new limbs.![]()

Heidi Hausse, assistant professor of history, Auburn University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.