Clinton Yates takes readers inside all things MLB’s first game in Birmingham, Alabama at Rickwood Field, the oldest professional baseball stadium in the United States.

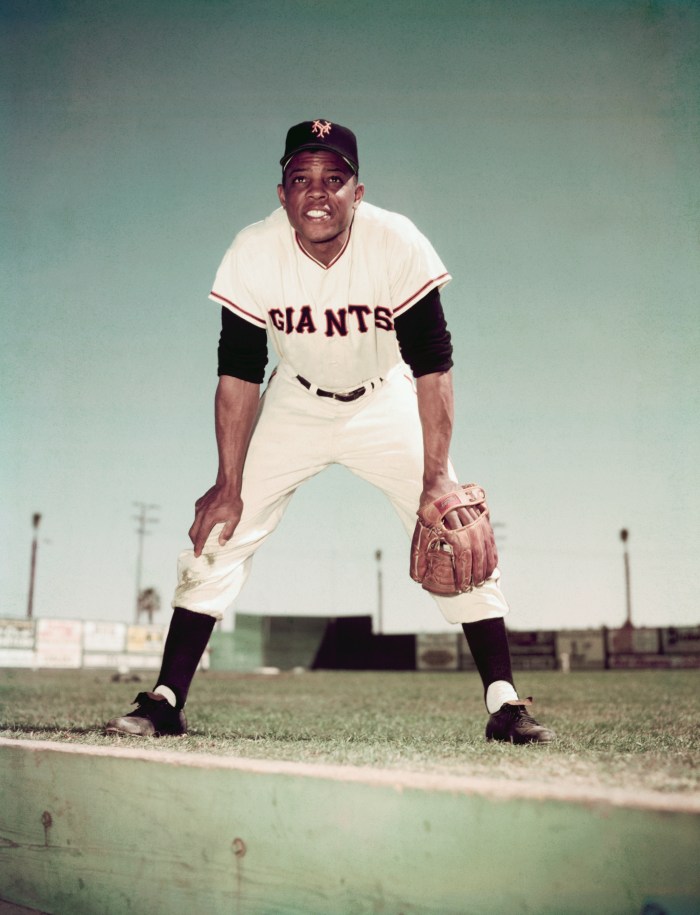

Editor’s note: The San Francisco Giants announced that Willie Mays died Tuesday afternoon at 93 years old.

BIRMINGHAM, Alabama — Long after the curtain closed at the historic Carver Theater on 4th Avenue, two New Yorkers were arguing about basketball. The resurgence of Kristaps Porziņģis and the Boston Celtics, who in about two hours would win their 18th NBA championship, is a confusing prospect for these New York Knicks fans.

But these aren’t just any guys from New York. One of them is the legendary cultural mathematician Nelson George. The other is Willie Mays’ son, Michael. The two men had just finished a question-and-answer session after a screening of the HBO documentary. Say hello, Willie Mays!, that brought people of all types to the building that also houses the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame.

The position was no small feat. Everything from traditional African clothing to the Sunday service was on the backs of those in attendance, and the outing featured more stories about arguably the greatest baseball player of all time, told by people who knew him. had encountered in all walks of life over the years. .

The spiritual presence of Willie Mays, if you will, concerns everyone. It’s his hometown. But the 1954 World Series champion won’t attend the first MLB game to be played at Rickwood Field, where he first roamed the spacious grass of center field in 1948 in the Negro American League for the Black Barons from Birmingham at the age of 17.

“He’s 93. That’s a lot,” Michael Mays said onstage about his father’s decision not to be there. “I think basically what it is is he doesn’t show up halfway. And I think he feels like, you know, we’ve all introduced him, just show up. And you know, you just do your little thing, and it will make all the difference in the world. No, if he can’t stop and do what he does with each person, and give everyone their due and their time, he feels like he’s cutting corners, and he won’t do that.

Fair enough. When you’re an American icon whose presence and skills have helped transform various major tenets of society – baseball and, for example, the television industry, to name a few – you don’t things on no one’s terms other than your own.

Bettmann

If you’ve never seen the 2022 film Nelson directed, it’s well worth your time. The project sees Mays as an allegory for how this country grew over those years, while various characters we all know from the world of sports and pop culture talk about how much Mays changed their lives and their career.

“Willie was so naturally effervescent, so talented as a storyteller and so comfortable in front of the cameras, that much of white America felt comfortable with him,” said sports commentator Bob Costas in the movie. “I remember asking Willie about it. There are no black people in any of these sitcoms, but Willie Mays would just appear, as if it were a natural evolution. So here’s Donna Reed having lunch with a white lady, and all of a sudden Willie Mays shows up. The incongruity of the scene apparently escaped most viewers, and then he walked away with the check.

Costas recalling this kind of unique scenario with an incredulous laugh isn’t the only laugh-out-loud moment in the film, but the emotions in the theater which is located in Birmingham’s civil rights district were quite palpable. When the story gets to the point in his career when he was playing for the Mets in the 1972 World Series but didn’t get a final at-bat in a crucial situation after returning to New York, there was an audible groan from the crowd.

“I’ve been here a lot lately, I also filmed another project in Selma last year,” George told a packed house. “I think my perception of the South and Alabama has definitely changed by being here. And meeting people and seeing the relationship between the history that we know and the reality of life from the ground, and so much of what happens in the narrative is conflict. Most people are motivated by conflict and how they tell their stories. And it’s certainly very attractive. But there is a nuance and interaction between people here that is very unique. One thing we tried to do in the film was connect Willie to the story.

In Birmingham, you don’t have to go far to connect with this history, because it’s all around you. Right there on 4th Avenue, it doesn’t seem like much has changed since the Fairfield Industrial High School product arrived. Down the block, a restaurant called Green Acres serves delicious fried catfish with lots of old-timey photos on the walls. It’s the kind of place where there’s a newspaper framed with the first inauguration of then-President Barack Obama and a CD jukebox that plays lots of gospel music.

“An astonishing film. I never thought a baseball documentary would bring tears to my eyes,” Samantha Briggs, vice president of education at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, said during the session. “But I was sitting here booing. So thank you I love how you brought out the story of the fathers, (which) really stood out as something special.

Of course, the best stories are often not the ones told in front of everyone. These are the ones who stay in the editing room.

Bettmann

“You know, it’s funny. I originally presented a four-hour documentary, right? »

George discusses how this film could have become a miniseries in its own right, because of the breadth of Mays’ life and the people he met. There were simply too many topics to reasonably discuss. But my favorite story concerns another star, his contemporary, the singer Frank Sinatra. The two, along with the rest of the Rat Pack, often ran in the same circles.

The short, safe-for-work version is that once Sinatra started getting white women to hang out with the guy known as Buck, Mays simply stopped answering Sinatra’s phone calls to party in public. Imagine having the kind of juice where Ol’ Blue Eyes and his team make desperate attempts to get you to play with them.

Listening to Michael Mays tell his father’s childhood stories made me think of so many different family reunions I’ve attended over the years. The part where, after everyone has left the barbecue, the uncles are still sitting in the backyard and telling stories while the kids try to stay awake just to see what they can do.

Black men showing each other love and uplifting each other through the reminder of our experiences is what has kept so many players motivated enough to keep going. And the only person you could credibly believe would hang up on the 44th president of this country for simply making a phone call and not showing up in person at his birthday party, or for hilariously refusing the St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson from home. when he was in town for a lunch invitation, it was Willie Mays. Because of course.

“He was first to the party as far as what we do. Even though all this energy was building up, I think it’s very relevant,” Michael Mays said as confetti fell in TD Garden on a nearby television. “Also, Nelson is the only one to tackle this Uncle Tom thing, but to do it appropriately, he didn’t run away. He didn’t dodge that. Also, to get dad to talk about his mom. He never, ever talks about Annie. He called me and said, “Would that be cool?” I was like, “Man, I don’t know.” And he did it and you know, some risk-taking paid off, right?

As for George, he has been documenting the lives of Black Americans for longer than I have and has shown the world things we would never have seen without his vision. His experience at 114-year-old Rickwood Field for the documentary is one that many people will also feel when they walk through the turnstiles.

“I’ve been making books and movies and art and stuff forever,” Nelson said with the smile of a child who fell in love with the game a long time ago. “This field day was the most fun I’ve ever had.”