Primordial

There are the classics, and then there is “Chinatown”. First released on June 20, 1974, the seminal noir feature was a resounding success at the time: a big success for producer and Paramount heavyweight Robert Evans, a notable return to Hollywood for director Roman Polanski and an Oscar for screenwriter Robert Towne, as well as Oscar nominations for stars Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway.

But the film has only become more entrenched in the canon in the decades since, particularly for Towne’s screenplay: a dark portrait of the uninhibited greed shaping Los Angeles in the 1930s, celebrated as the ‘one of the best – and often cited as THE best – story scenario. Key to its legacy is its terrifying ending, which sees Nicholson’s detective JJ Gittes return to his old stomping grounds of Chinatown. There, he witnesses another deadly miscarriage of justice that he is unable to stop.

That Towne initially objected to the ending is the stuff of Hollywood legend. Not only did the screenwriter initially envision a more triumphant conclusion for Gittes, but he was also opposed to returning the story to Chinatown. As David Fincher says in the commentary for his DVD with Towne: “The ultimate would be to never have to go to Chinatown.” … Chinatown couldn’t be a place you could actually go because it’s a state of mind.

In the years since, Towne has consistently maintained that he now believes Polanski’s reimagined ending is the correct one. Now 80, the screenwriter even returned to “Chinatown” himself, working with Fincher to write a prequel series that explores Gittes’ time as a new detective patrolling the neighborhood that would come to haunt him.

“All I will say is yes, all the episodes were written for Netflix,” Towne writes in an interview with Variety. “Working with a force of nature like David Fincher, while humbling at times, is never less than enlightening.”

Netflix has not commented on the project. (The streamer didn’t have one either when the series was first reported in development in 2019.) Nonetheless, Towne’s vision for the prequel seems consistent, shedding light on the tragic events that made Gittes a private detective instinctively cynical (wrongly). that he is in the original Polanski film.

John Huston and Jack Nicholson in “Chinatown”

Primordial

“When David and I started talking, we agreed that we wouldn’t try to replicate Noah Cross,” Towne said of the series villain. “But we wanted to keep in mind that the crimes that history considers monstrous are those that will not stay in the past but insist on visiting the future, and I think we achieved that.”

In particular, Towne and Fincher’s screenplays explore the relationship between a young Gittes and his colleague Lou Escobar. Played by Perry Lopez in the 1974 film, Escobar is more of an obstacle than an ally for Gittes in this story. But their shared history as police partners patrolling Chinatown, as well as Escobar’s presence during the Gittes tragedy, are both touched upon throughout the film.

“Chinatown, with all its implications for a changing Los Angeles, is essential to understanding the evolution of Jake Gittes, as is his friendship and dependence on his partner Lou Escobar,” Towne said. “It was enlightening to delve into their history, that of Escobar in particular. The little details covered in the film come to life and scale in a way that even surprised me.

Jack Nicholson and Perry Lopez in “Chinatown”

Everett Collection

The as-yet-unmade Netflix series, however, would not be Towne’s first continuation of “Chinatown.” A sequel, “The Two Jakes”, was written by the screenwriter and directed by Nicholson himself. In the years leading up to production, Nicholson referred to “The Two Jakes” as part of a “triptych” of feature films, hinting at a potential third installment in a so-called “Chinatown” trilogy, which would have continued to monitor development and corruption. of 20th century Los Angeles.

“For me, ‘Chinatown’ began when I was living in Benedict Canyon and a real estate developer bought land near Deep Canyon and started a rapacious construction company. Land was being destroyed because of greed,” says Towne.

“The Two Jakes” was released in 1990: the same year as another late (but more award-winning) bite at the New Hollywood apple, Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather Part III.” The sequel finds Gittes resettled in 1948 in Los Angeles after serving in World War II. Now the owner of his own office building and a member of a country club, the private eye has become complacent and, as the New York Times put it in its review, “older (and broader).” But when a new real estate conspiracy centered on oil fields arises, Gittes becomes possessed again by his latent morality, discovering surprising links with the Cross affair that haunts him.

Jack Nicholson directs “The Two Jakes”

Paramount/Everett Collection

After multiple collapses during pre-production over the years, the much-delayed “Two Jakes” was immediately labeled a disappointment upon its release, earning mixed reviews and failing to recoup its budget theatrically. Any enthusiasm for a trilogy-capper was quickly crushed, although details of the project have emerged in dribs and drabs over the years. A potential title has even been launched: “Gittes against Gittes”.

Both Towne and Nicholson reportedly said a third Gittes story occurred after California enacted no-fault divorce, meaning a marriage could be legally terminated without requiring either party to prove wrongdoing the other. Naturally, such a law could have put an end to Gittes’ detective work; investigating and photographing infidelities is his livelihood.

Although Towne refuted the idea that “Chinatown” was originally intended as the start of a trilogy, he says a third Gittes film was considered a possibility. However, when asked about “Gittes vs. Gittes”, the screenwriter shares that he stopped thinking about story ideas after finishing the script for “The Two Jakes”, then left the sequel before the start of filming.

“The questions, while intriguing, have no answers, at least none that I can give. My involvement with “The Two Jakes” ended before Jack directed the film. And with that comes all speculation about where Jake Gittes is and what he might be doing at a later date,” Towne says. “A character does not appear as fully formed like Athena from the head of Zeus. The way in which he or she evolves or develops is, let’s face it, the main job of the screenwriter. Jake Gittes was in his thirties in “Chinatown.” And whatever I may have speculated in my late thirties is probably not what I would dare to create now.

“That’s why I love the prequel which places Gittes newly in Los Angeles. … It’s this young Jake Gittes that I’m particularly drawn to,” Towne continues. “Because for all his bravado – his rule-breaking, his penchant for ruling – he controls events far less than events control him. And by the time he realizes it, it’s far too late to do anything, which seems to me to be the fate of the very young and the very old.”

Faye Dunaway and Jack Nicholson in “Chinatown”

Primordial

Towne has also spoken over the years about how Nicholson’s character was a formative influence in his writing of Gittes. The couple’s history dates back to a performance class in the late 1950s taught by then-blacklisted actor Jeff Corey. The two became friends and lived together as roommates before Towne wrote the screenplay for Hal Ashby’s “The Last Detail” and with it, one of Nicholson’s most memorable roles. Gittes’ character was also calibrated for the actor.

“From the moment I saw him, I knew Jack was going to be a star. … I couldn’t have imagined anyone else in the role,” Towne says. “It wasn’t just about his capacity for indignation, about an innate feeling that the world might not be fair, but that it should be. It was also his passion for clothing, a certain eye for beautiful things, a contempt – even an aversion – for the ordinary.

Towne’s concerned approach to acting was not unique to “Chinatown,” however. The screenwriter has written for stars throughout his career, including Tom Cruise for their inaugural collaboration “Days of Thunder” and the first two “Mission: Impossible” films. This also happened with Towne’s second feature, “Tequila Sunrise,” which saw Kurt Russell get one of his most stylish roles as a suit-wearing narcotics detective, Nick Frescia.

“Having a real person to write for makes my job easier and more enjoyable,” Towne says. “I knew Goldie Hawn from ‘Shampoo’ and through her I met Kurt Russell, the bad boy with the best heart you’re likely to meet. Nick Frescia was supposed to be Kurt. Or look at Tom Cruise. He’s a wonderful actor who’s played many roles, but just like seeing (James) Cagney walk or Jimmy Stewart walk, you know it’s Tom from the first shot, that fierce energy, and so if you’re writing for him, you are halfway there. there in terms of character.

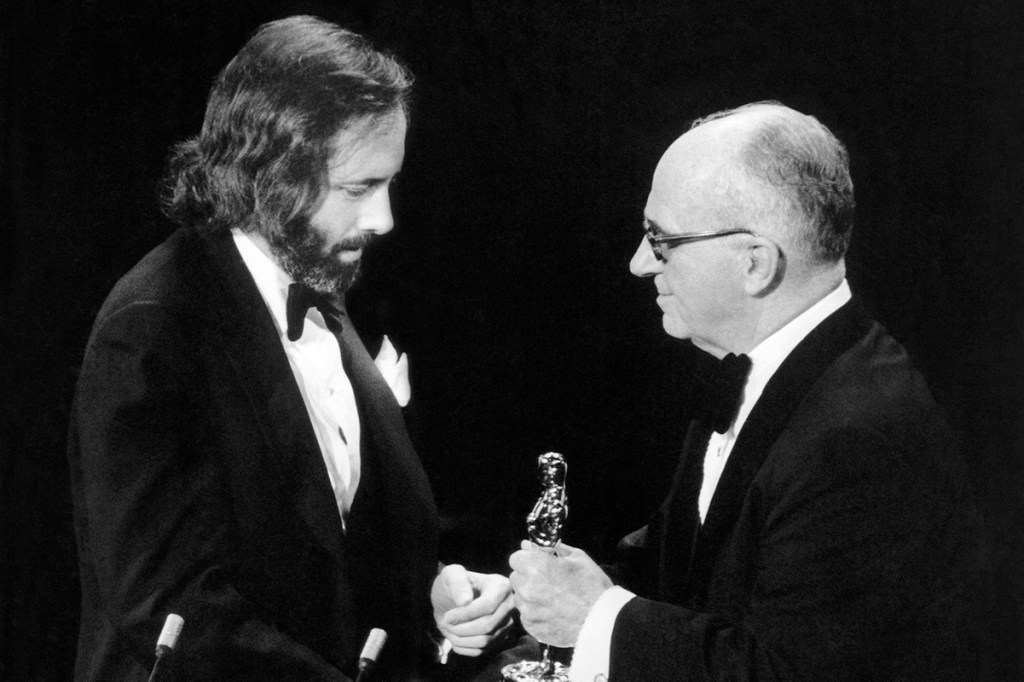

Robert Towne receives the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay from James A. Michener at the 1975 Academy Awards.

Everett Collection

A longtime screenwriter, Towne has seen the film industry shift from New Hollywood to streaming. Writing for Lapham’s Quarterly in the mid-’90s, he asked an existential question about his profession that seems only more relevant in the fragmented attention context of the digital age: “It’s difficult to write effectively without a ground of understanding between you and your audience. Shared beliefs, like shared experiences and shared myths, provide this foundation. … For me, this is the problem that the contemporary screenwriter faces: how can he tell a compelling story when nothing seems obvious to the audience?

“I’m not sure what my mindset was when I said that, but what I will say now is that storytelling doesn’t stop just because one culture uses different mechanics,” says Towne when asked about the article. “The public always wants to believe it. They are simply more sophisticated, they have become accustomed to cinema and therefore are not so easily fooled.

The new 4K Ultra Blu-Ray of “Chinatown” is now available from Paramount Presents.