More than 85% of women – and more than 300 million people worldwide at any given time – use hormonal contraceptives for at least five years of their lives. Although they are primarily used for contraceptive purposes, many people also use hormonal contraceptives to manage a variety of menstruation-related symptoms, from cramps and acne to mood swings.

However, for up to 10% of women, hormonal contraceptives may increase the risk of depression. Hormones, including estrogen and progesterone, are essential for brain health. So how does changing hormone levels with hormonal birth control affect mental health?

I am a researcher in the neuroscience of stress and emotion-related processes. I also study gender differences in vulnerability and resilience to mental health disorders. Understanding how hormonal contraceptives affect mood can help researchers predict who will experience positive or negative effects.

How do hormonal contraceptives work?

In the United States and other Western countries, the most common form of hormonal birth control is “the pill” – a combination of synthetic estrogen and synthetic progesterone, two hormones involved in the regulation of the menstrual cycle, ovulation and pregnancy. Estrogen coordinates the scheduled release of other hormones, and progesterone maintains the pregnancy.

This may seem counterintuitive: why do the natural hormones necessary for pregnancy also prevent pregnancy? And why does taking a hormone reduce levels of that same hormone?

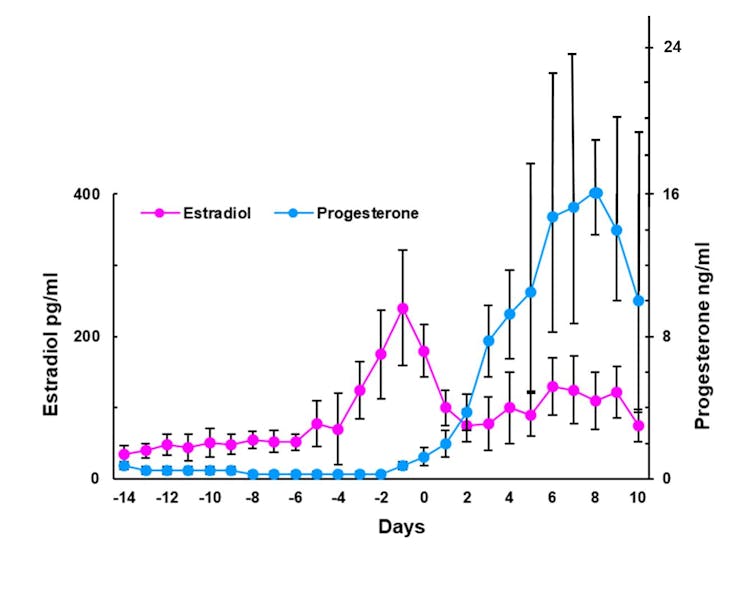

Dharani Kalidasan/RI McLachlan et al. 1987 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Hormonal cycles are tightly controlled by the hormones themselves. When progesterone levels rise, this activates processes in cells that stop the production of additional progesterone. This is called a negative feedback loop.

Estrogen and progesterone from the daily pill, or other common forms of birth control such as implants or vaginal rings, cause the body to decrease its production of these hormones, reducing them to levels seen externally. of the fertile window of the cycle. This disrupts the tightly orchestrated hormonal cycle necessary for ovulation, menstruation and pregnancy.

Brain effects of hormonal contraceptives

Hormonal contraceptives not only affect the ovaries and uterus.

The brain, specifically an area called the hypothalamus, controls the timing of ovarian hormone levels. Although they are called “ovarian hormones,” estrogen and progesterone receptors are also found throughout the brain.

Estrogen and progesterone have broad effects on neurons and cellular processes that have nothing to do with reproduction. For example, estrogen plays a role in processes that control memory formation and protect the brain from damage. Progesterone helps regulate emotions.

By changing the levels of these hormones in the brain and body, hormonal contraceptives can modulate mood – for better or worse.

Hormonal contraceptives interact with stress

Estrogen and progesterone also regulate the stress response – the body’s “fight or flight” response to physical or psychological challenges.

The main hormone involved in the stress response – cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rodents, both abbreviated to CORT – is primarily a metabolic hormone, meaning that increased blood levels of these hormones during Stressful conditions result in the mobilization of a greater amount of energy from fat stores. The interplay between stress systems and reproductive hormones provides a crucial link between mood contraceptives and hormones, as energy regulation is extremely important during pregnancy.

So what happens to the stress response of someone who takes hormonal birth control?

When exposed to a mild stressor – putting an arm in cold water, for example, or standing up to give a public speech – women using hormonal contraceptives had a smaller increase in CORT than people who are not taking hormonal contraceptives.

Vera Livchak/Moment via Getty Images

Researchers saw the same effect in rats and mice: When treated daily with a combination of hormones that mimic the pill, female rats and mice also showed a suppression of the stress response.

Hormonal contraceptives and depression

Do hormonal contraceptives increase the risk of depression? The short answer is that it varies from person to person. But for most people, that’s probably not the case.

It is important to note that neither increased nor decreased stress responses are directly linked to depression risk or resilience against it. But stress is closely linked to mood, and chronic stress significantly increases the risk of depression. By modifying stress responses, hormonal contraceptives modify the risk of depression after stress, leading to “protection” against depression for many people and an “increased risk” for a minority of people. More than 9 in 10 people who use hormonal contraceptives will not experience a drop in mood or symptoms of depression, and many will experience an improvement in their mood.

But researchers don’t yet know who will be at increased risk. Genetic factors and prior exposures to stress increase the risk of depression, and it appears that similar factors contribute to mood changes related to hormonal contraception.

Currently, hormonal contraceptives are typically prescribed by trial and error: If one type causes side effects in a patient, another with a different dose, delivery method, or formulation might be better. But the process of “trying and seeing” is ineffective and frustrating, and many people give up instead of moving on to another option. Identifying specific factors that increase the risk of depression and better communicating the benefits of hormonal contraception beyond birth control can help patients make more informed health care decisions.