Part of an ongoing process weekly series Alaska History by Local Historian David Reamer. Have a question about Anchorage or Alaska history or an idea for a future article? Fill out the form at the bottom of this article.

To win an argument against a Frenchman, you have to produce momentum. This may seem like the worst attempt at creating an aphorism, but this is how Thomas Jefferson defended American honor and handled an academic dispute. This article may not be about Alaska, but it focuses on a topic Alaskans know all too well: moose. And Alaskans certainly know far more about moose today than any European scholar did in the 18th century.

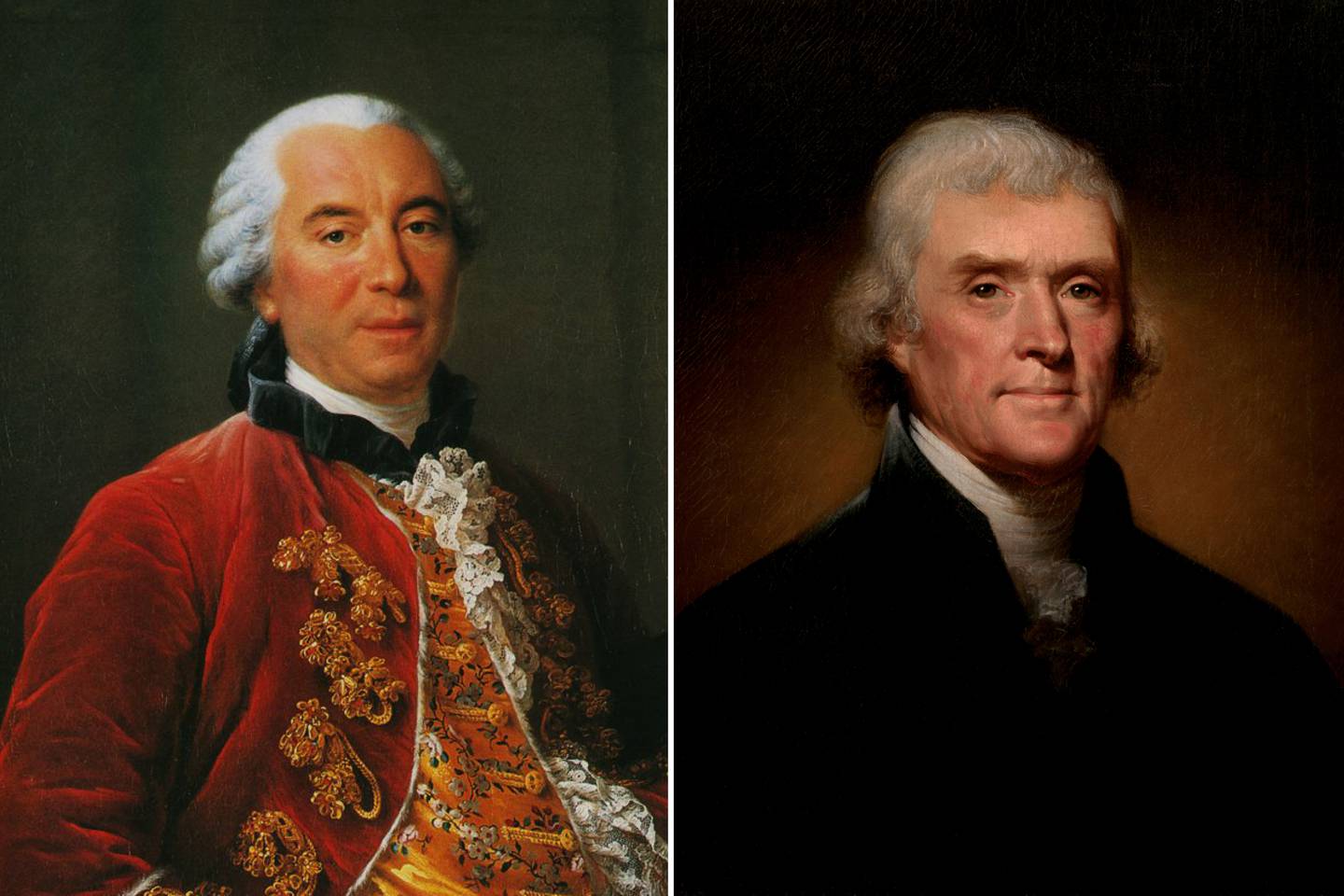

George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788), in English Comte Buffon, was a French naturalist and author, one of the most acclaimed scholars of his generation. Although less appreciated today, in his day he was considered a worthy peer of intellectual heavyweights such as Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Buffon’s masterpiece was a 36-volume “Natural History: General and Particular”, a mineral and zoological encyclopedia published between 1749 and 1788.

Written in an engaging and often poetic style, each volume was a cultural sensation, reprinted and translated many times into several other languages. Anyone with any literary or intellectual pretensions owned copies. The “Natural History” volumes were among the best-selling books of the eighteenth century. Short chapters devoted to specific animal species make up the bulk of the series: larks followed by warblers, and so on. But he also included more general treatises on the natural world, including his theory of the degeneration of animals and man on the North and South American continents.

Buffon believed that the animals and indigenous peoples of the American continents were degenerate compared to those of other continents. His use of the term degeneracy does not refer to the immoral sense of the term, but to the fact that the animals and peoples were inferior: smaller, weaker, and less prolific. Animal data were his primary evidence. For example, he noted that the big cats of the Americas were smaller and “more cowardly” than lions. He also argued that the absence of elephants, camels, rhinoceroses, and giraffes in the Americas meant that “living nature is therefore much less active, much less varied, and, we may even say, less strong.” Furthermore, he argued that species from elsewhere transplanted to the Americas would necessarily degenerate. The negative implications of this situation were not lost on the inhabitants of some of the British colonies along the eastern coast of North America, those which became a new independent nation in the last years of Buffon’s life.

Buffon’s self-aggrandizing theory – given its continental origins – was far from new and far from the last of its kind. Variations have existed since the time of the ancient Greek philosophers, beliefs that lands beyond the author’s own possessed inferior flora, fauna, and inhabitants. When Queen Isabella of Spain, of the Ferdinand and Isabella who sent Christopher Columbus westward, heard the first reports of the newness of her world, she remarked: “This land, where the trees are not firmly rooted, must produce men of little sincerity and unscrupulousness. less consistency. The English poet John Donne (1571/1572-1631) described the Americas as “the immature side of the earth.” And the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was at least partially influenced by Buffon in his 1837 text “Lectures on the Philosophy of History” when he wrote: “America has always shown itself physically and spiritually powerless, and she still does it today. »

When it came to the animals of the Americas, Buffon did not know or understand caribou, large bears, musk oxen, elk, and bison well. Of elk in particular, Buffon wrote disdainfully that they were “considerably smaller in America than in Europe, and that without exception.” It should be noted that the French nobleman never visited the Americas. Instead, he relied on other people’s accounts, sometimes little more than rumors. At some point, the insult to the United States became too obvious. This is how Thomas Jefferson trained.

By the early 1780s, the future president was aware of Buffon’s claims and was dismayed by the apparent critical failures, particularly in the quality of data collection. In “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Jefferson’s only complete work, he sharply criticized the theory of American degeneration. Of Buffon in particular, he wrote: “There has been more eloquence than sound reasoning deployed in support of this theory; that it is one of those cases where judgment has been seduced by a glowing pen.”

Jefferson spent most of 1784 to 1789 in France as a trade negotiator and, subsequently, as the official United States minister to France. This position offered him more direct opportunities to refute Buffon and his supporters; “Notes on the State of Virginia” was first published anonymously in 1785 in Paris. In 1786, Jefferson even dined at Buffon’s house, where the count acknowledged a minor taxonomic error but otherwise refused to modify his beliefs about American degeneration.

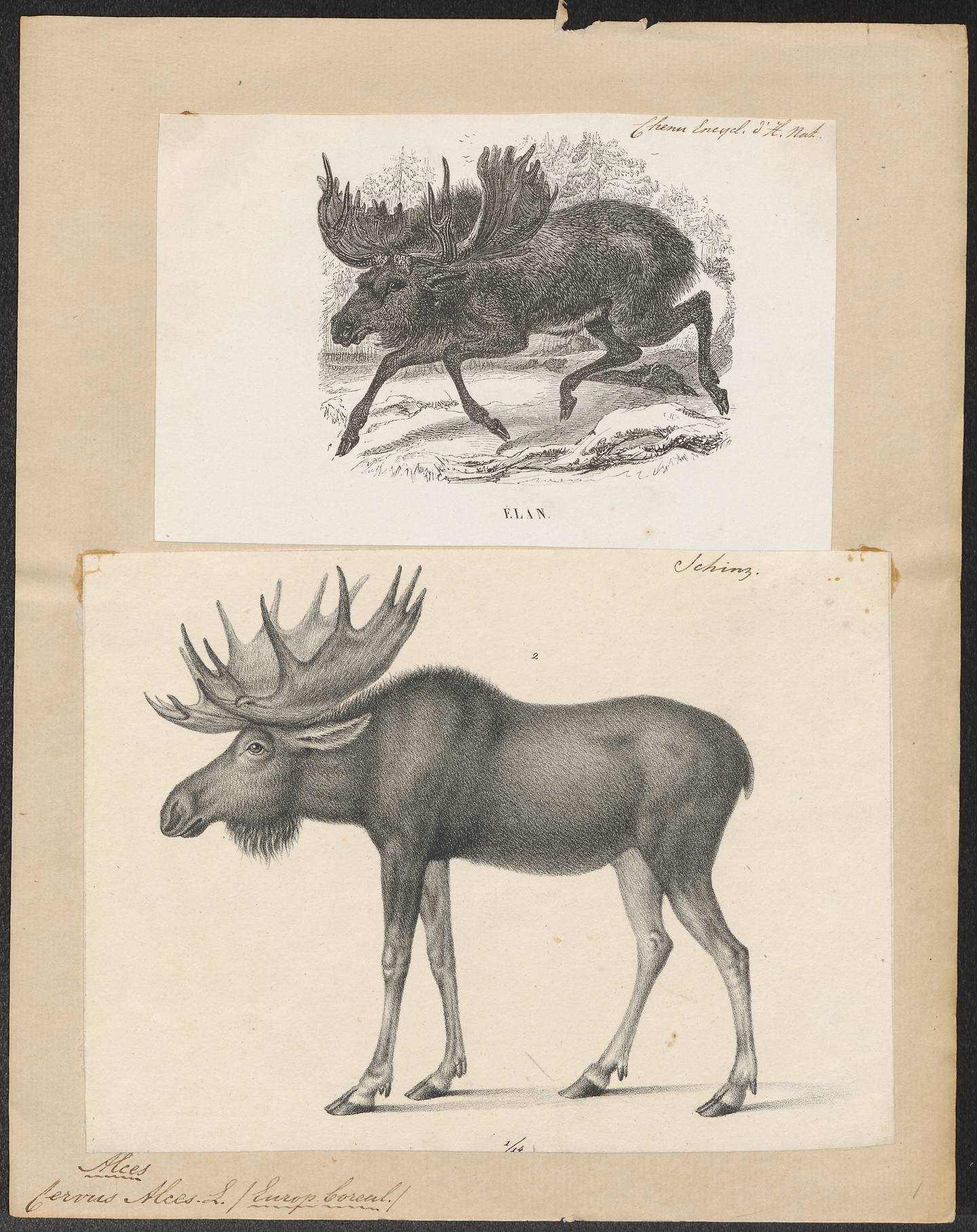

Jefferson had argued like a scientist up to that point, with measurements, animal skins, and fossils, but he had always been rebuffed for trivial things, or even ignored altogether. He needed a little more shock and awe to shake up European minds, a spectacular response that could not be ignored. He needed a specimen so large and grandiose that it could singularly contradict the arguments about small American wildlife. As any Alaskan would understand, he opted for a moose. However, he needed a real moose, not notes or antlers, sent to France.

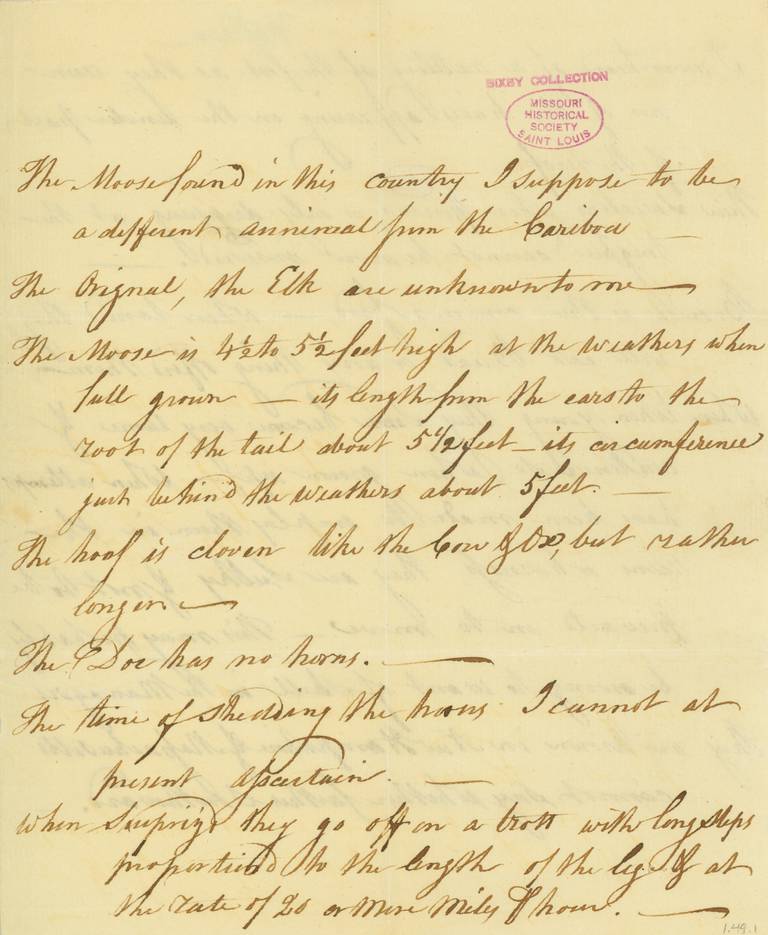

Elk were a particularly suitable target, as Buffon did not believe they existed as a species in their own right, thinking they were instead classified as reindeer. And for a Virginia resident, Jefferson was an elk expert. He had already been researching elk for several years. Before leaving for France, he had sent questionnaires to his colleagues (the prolific statesman and writer had many colleagues) regarding elk, asking them about their behavior and size. Among those interviewed was John Sullivan, a general in the American Revolution and future governor of New Hampshire.

Sullivan, who had witnessed Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River, among other battles, wrote to Jefferson in January 1787 to bring him the good news. He had in mind, if not in hand, an impulse. In his enthusiasm, he wrote to Jefferson a little prematurely. Had he known the difficulties to come, he might have waited.

At the time of this letter, the moose in question lay dead in a remote area of Vermont. From there, it took 14 days and the clearing of a 20-mile road in the middle of a particularly harsh winter before the moose arrived at Sullivan’s home. Moreover, in his eagerness to help Jefferson, Sullivan had failed to take into account his complete lack of training as a taxidermist. Once prepared, the moose still had to make a long sea voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to England, then to the French port of Le Havre, and from there to Paris.

The substantial costs of the project were more than ruinous for Sullivan. He had to borrow money from his brother for transportation. In a detailed expense report, he wrote: “I only charge for expenses that I paid for in cash, with nothing for my own efforts which were very considerable. »

Jefferson finally received the object of his desires near the end of September. The moose, once a striking example of its species, was a chaotic assortment of skin and bones after months of questionable taxidermy and shipping delays. It was more of a kit than a specimen. Sullivan had managed to preserve most of the skeleton, except for the head and antlers. As for the head, he writes, “the skin being whole and well dressed, we can draw it at will”, an uninspiring option. A set of replacement wood was included and “can be attached at will”. Worse still, as Sullivan writes, “the moose’s skin was covered in hair, but much of it has come off and the rest is ready to fall off.”

From this assortment of elk pieces, the author of the Declaration of Independence was able to reconstruct a stuffed elk. On the surface, he was certainly worse than he could have been. Despite his strong ties to the country, Jefferson had little chance of convincing anyone else to kill, prepare, and ship an elk to France on his behalf, so he made do. A modern-day Alaskan might have wondered how many diseases the moose contracted before it died, but it must have been a startling sight to Europeans of the time.

(The Mystery Meat of 1951: Did an Exclusive Club Eat a Frozen Woolly Mammoth from the Aleutian Islands?)

The elk was duly delivered to the count. In a letter to Daniel Webster, Jefferson wrote that Buffon “had promised in his next volume to set the record straight.” But the Frenchman did not respond, neither with a crude insult, nor a formal refutation, nor an apology. More to the point, he died within six months of the elk’s arrival. There is surely no causal connection between the two events, though it is amusing to imagine that the sight of an American elk sent the Frenchman into a death spiral of shame and remorse. American pride demanded a response; perhaps this was it.

• • •

• • •

Key sources:

Dugatkin, Lee Alan. Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Nature History in Early America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Gerbi, Antonello. The New World Quarrel: History of a Controversy, 1750-1900. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973.

Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

Webster, Fletcher, editor. The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster, Volume 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1857.