“Our goal with this strike is to disrupt production,” union leader Son Woo-mok said. (Photo: Bloomberg)

By Jenny Lee, Yoolim Lee and Sohee Kim

More than 6,500 Samsung Electronics Co. workers walked off the job Monday to stage a rally demanding better wages, marking the start of the largest organized labor action in the South Korean conglomerate’s half-century history.

Disgruntled workers and union supporters gathered in pouring rain outside one of Samsung’s largest chip manufacturing facilities south of Seoul. Wearing red headbands proclaiming “total strike” and black raincoats, they chanted slogans and sang songs while raising their fists. Union leaders, who provided an initial count of participants, hope the high-profile demonstration will galvanize a three-day strike that will send a message to Korea’s largest company.

Samsung’s main union has spent weeks preparing for the strike after negotiations over wages and leave broke down last month. The proposed action marks an escalation from a one-day strike in early June, the first in Samsung’s 55-year history. It is aimed at sending a message by disrupting production at one of the company’s most advanced chip factories, union leaders say.

The union had planned to gather up to 5,000 people for the rally outside Samsung’s plant in Hwaseong, about 38 kilometers south of Seoul, Lee Hyun-kuk, the union’s deputy secretary-general, told Bloomberg News on Friday. It’s unclear how many workers will actually walk off the job in the coming days, and markets have remained quiet so far. The company’s shares were largely unchanged Monday morning.

The risk, however, is that Samsung’s unprecedented move could hurt the country’s best-known and richest company and spark similar reactions across the tech sector. The union said many of the protesters were workers on chip assembly lines.

“Our aim with this strike is to disrupt production,” said union leader Son Woo-mok.

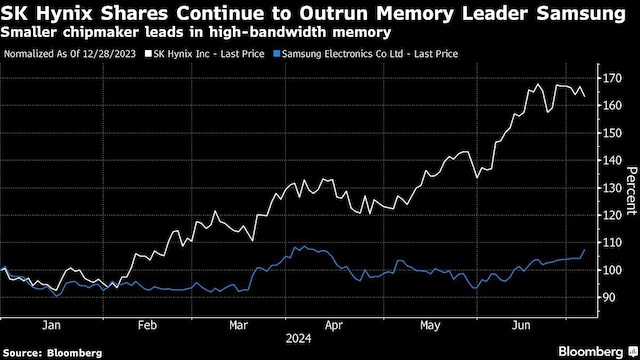

Samsung can’t afford to have turbulence in its ranks — or production slowdowns — at a critical time. The company is now scrambling to convince Nvidia to use its high-end AI memory chips — a prerequisite for a bigger stake in a booming AI market. In May, it abruptly replaced the head of its semiconductor division, which since 2023 has seen SK Hynix dominate the crucial high-speed memory, or HBM, chip business.

Samsung is preparing to unveil new foldable phones and watches and a smart ring in Paris this week, ahead of the Olympics, in a bid to leapfrog Apple Inc. in its global market lead. But Samsung has anticipated a rebound in global demand for memory and electronics from the historic lows of the post-Covid era: the company reported a 15-fold increase in profits on Friday, but on a very low 2023 base.

Samsung representatives declined to comment as of Friday.

“The timing of this strike is particularly critical because it coincides with the current challenges in the semiconductor supply chain,” said Billy Leung, investment strategist at Global X Management Co., a member of Mirae Asset Financial Group. Samsung accounts for about 20% of the global DRAM market and about 40% of NAND flash, which is used in smartphones and servers. “Any disruption to Samsung’s business could have a domino effect.”

Samsung Electronics has long avoided the turbulence that has hit many major Korean companies, from Hyundai Motor Co. to Ssangyong Motor Co., with strikes sometimes turning violent in the past. Analysts attribute its success to Samsung’s tight control over labor militancy, which allowed the company to dominate the electronics sector from its perch in Suwon for more than a decade. Lee Kun Hee, Samsung’s former chairman and the father of current CEO Jay Y. Lee, has gone to great lengths to prevent unions from forming.

Now, the National Samsung Electronics Union, the largest of the tech giant’s many unions with more than 30,000 workers, says it is stepping up action over a breakdown in wage negotiations, after initially seeking a less dramatic resolution.

Union leaders have spent weeks encouraging their members to join the impending maneuver. On Thursday, Samsung tried to deflate the move by announcing first-half performance-related bonuses for semiconductor workers, but the promised maximum of 75% of monthly salaries was less than a full month’s pay, as has been the case in the past.

“Since executives are under contract, they are mostly concerned with performance and short-term goals,” said Park Seol, a 35-year-old who works at Samsung’s Pyeongtaek complex. “We stand up for what is best for the company.”

At the heart of the dispute now are wage increases and additional paid leave. Last week, union leaders amended their demands to include their entire workforce, after initially saying they wanted a bigger pay rise for about 855 employees who had not accepted a basic 3% annual increase.

Other issues include bonuses tied to Samsung’s excess profits, which chip workers did not receive last year when their division lost about 15 trillion won. Union leaders say they fear they will be left out again this year even if the division returns to profit.

Samsung calculates those bonuses using a complex formula that subtracts the cost of capital from operating income, adjusted for taxes on a cash basis. The union said it is asking the company to simply use operating income like some of its peers — or to be more transparent in how it determines those numbers.

Historically, bonuses have been a significant portion of workers’ salaries, so missing out on them can mean a significant reduction in compensation.

First published: July 08, 2024 | 7:49 AM EAST